Reassessing the assessment of pain: how the numeric scale became so popular in health care

Listen

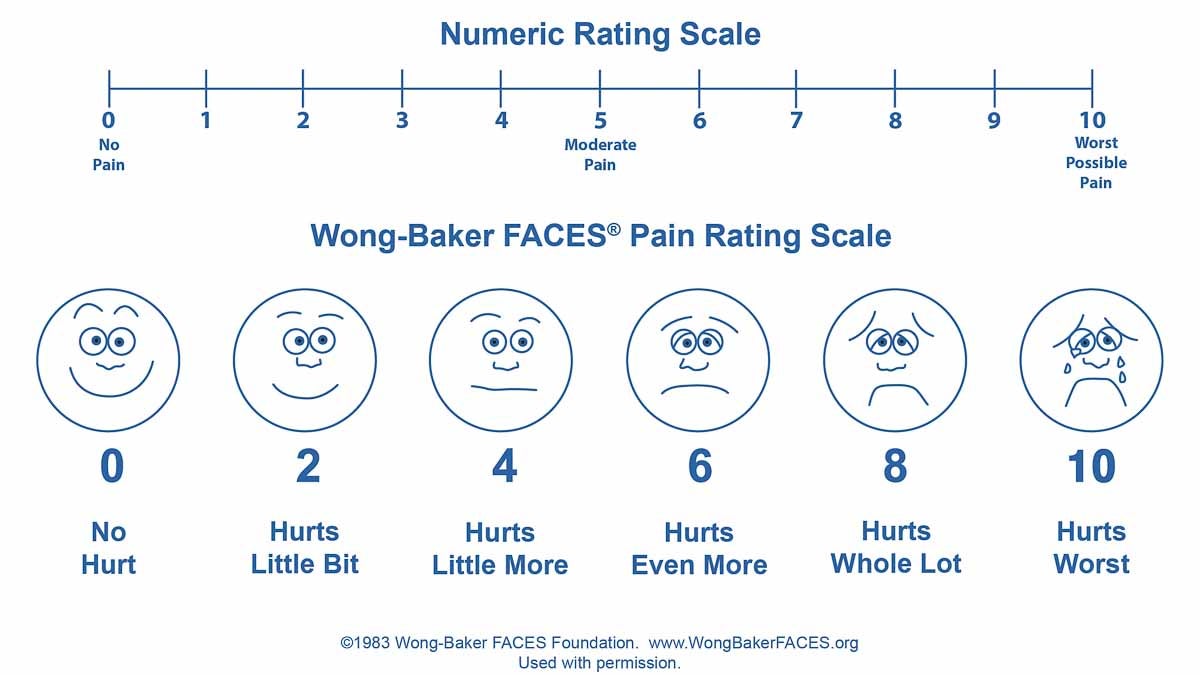

The Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale (Courtesy of Wong-Baker) was developed in the pediatric hospital setting by a pediatric nurse consultant and a child life specialist 30 years ago in Oklahoma. Children helped design it

It’s an experience that most everyone has had at a doctor or hospital visit, where at some point, usually early on, the question ‘on a scale of 0-10, what’s your level of pain?’ comes up. Then, before the visit wraps up, you may be asked that question again.

But the assessment of pain along with its treatment is being questioned right now. As is the way pain scales are applied in the exam room. While a numerical scale itself is not to blame, some worry the current approaches have contributed to the nation’s prescription drug epidemic. And even though that 0 to 10 assessment seems ubiquitous in health care today, it’s actually a relatively recent phenomenon.

The onset of 0 to 10

Dr. Katy Hicks doesn’t remember pain being discussed much when she was a medical student. This was in the late 90s in southern California.

“I don’t think that was part of the conversation at all,” said Hicks.

Then, during the first year or two of residency in internal medicine at the county hospital in Oakland, Hicks noticed a change. Along with checking blood pressure, temperature and other basic vital signs, nurses and doctors started asking patients about the intensity of their pain.

“It showed up on the paperwork first and really in the nursing documentation,” said Hicks, thinking back. “And then it became part of the conversation, that this was something that we should incorporate into our history, and that it was an additional vital sign, basically.”

Hicks doesn’t recall any special rollout. She says when a new measure appears, it usually has to do with updated standards or requirements. Either way, she found herself asking about pain, ultimately on a scale of 0 to 10, a few times over the course of a patient’s stay, and then recording it in her charts.

“I would be asking you, ‘what was your pain coming into the hospital and what is your pain now?’ And especially if someone was given medicine like tylenol, Motrin or morphine, you’d say ‘what was the pain before and what was the pain after?” said Hicks.

Under-treating pain

This wasn’t just a California thing. Around that time, the pain scale was spreading like wildfire across the country. That’s because the early 2000s marked a turning point in the culture of pain in America.

“And this really surprises people sometimes, but in 2000, Congress in fact declared the next decade the decade for pain, the decade for improving pain,” said Myra Christopher, a longtime chronic pain advocate with the Center for Practical Bioethics in Kansas City.

Christopher recalls the specifics of this shift very well. She was part of the movement that led to it. Then President Bill Clinton signed H.R. 3244 into law, making pain control and research a priority.

Several factors pushed the needle to this point. There had been growing recognition that pain was being vastly under-treated and not taken seriously. Christopher recalls the attitude had long been ‘just suck it up, deal with it,’ even after surgery. Doctors were extremely cautious of opioids.

But this was also a time when a huge portion of the population was getting older and dealing with chronic pain. In the wake of Vietnam and the Gulf War, the military increased its focus on veterans’ pain. Professional societies took up the issue. As did drug manufacturers. The main hospital accreditation agency stepped in.

“The Joint Commission in fact decided that they should make a quality measure about the assessment of pain, and the notion was if pain was assessed more often, then it would be treated better,” said Christopher.

So the commission began requiring that hospitals regularly assess pain as a measure of quality.

Zero to 10 wasn’t new. Identifying direct ways to assess and talk about pain with patients had also been part of advances in nursing well before the year 2000. But Christopher says it was around this time that the 0 to 10 approach became more institutionalized. After all, numbers can be a universal language. Pain…not so much.

“Western medicine is all about the objective, it’s about that which you can taste, smell, measure, weigh and touch We say all the time that pain, especially chronic pain, is an experience and it’s very, very subjective,” said Christopher. “So we were trying to figure out a way to advance from a physician or advanced practice nurse saying, ‘how’s your pain?,’ and someone saying, ‘oh my god it’s killing me, it’s driving nails in my joint!,’ to something that was more consistent and congruent with the clinical model.”

So maybe those driving nails in your joint would turn into something like…an eight.

Clinical trials and the emergence of scales

But 0 to 10 wasn’t initially designed for addressing patient’s pain. It was meant to be a tool to study it.

“The primary impetus for the development of the scales we use today was to standardize it, not so much for patients to tell us how much pain they have in the clinical setting, but to standardize it from the perspective of being able to study it for research purposes,” said Dr. John Farrar, a pain specialist and director of the Biostatistcs Analysis Center at the University of Pennsylvania. “Frankly all scales we use today were based on the development of those research enterprises.”

He helps design pain assessments used to study new treatments, and he has spent decades analyzing measurements. Researchers have come up with all sorts of approaches. Some have involved sensory comparisons, or applying some sort of heating pad or a sharp piece of plastic to a person’s skin.

As for the scales, there are many. To show for it, he has two filing drawers packed with pain scales, past and present. It includes everything from mood scales, to depression scales, to coping scales to side effects. Some are verbal, some use faces. Yes, emoticons were a hit in health care way before you could text them on your phone (that widely recognized wong-baker faces scale was actually developed in the hospital and patient setting, by a nurse and social worker 30 years ago, to help gauge children’s pain. It’s also used with people who speak other languages).

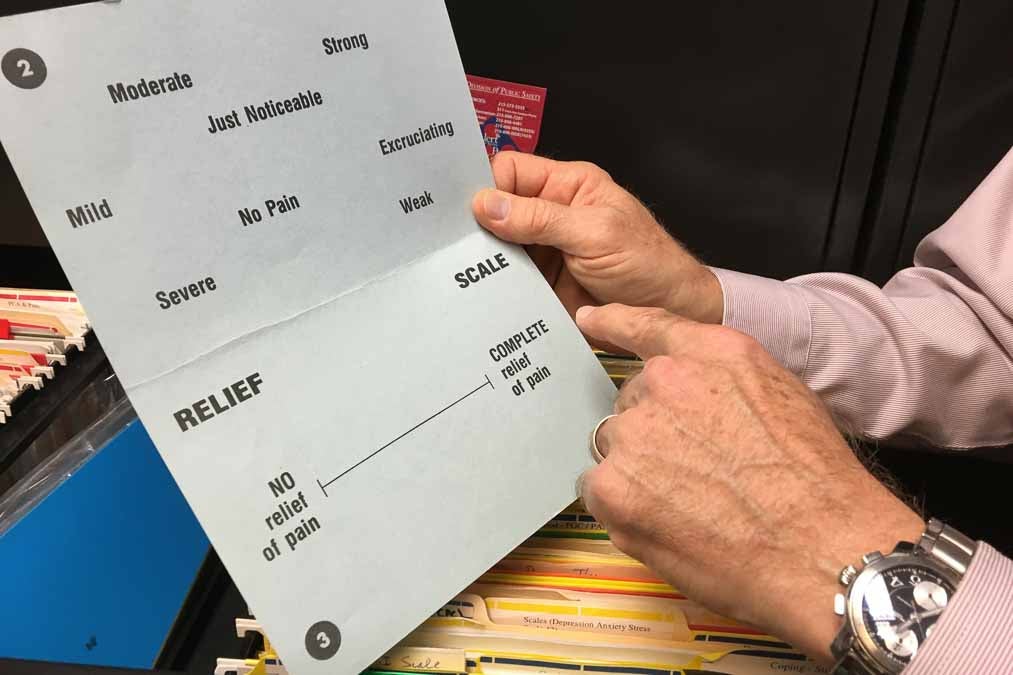

Early on, there was a four point verbal scale with no pain, mild pain, moderate, severe. There was a popular analogue scale that just had a horizontal line, representing a continuum of pain or mood, with 0 on one end for no pain, and 10 on the other for worst pain. The patient would mark where they fell on this.

Dr. John Farrar pulls out an original Memorial Pain Assessment Card, designed by his mentor, Dr. Raymond Houde, whom Farrar credits as developing many of the pain scales used today. Farrar describes this visual analague scale as a precursor to the numeric one. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

Farrar says it was the onset of clinical trials right after the Second World War that led to the development and use of pain scales, and more specifically numerical scales. Researchers wanted a standardized way to measure whether patients were benefiting from a treatment or not. One way to detect that would be to measure whether patients reported changes in their pain score.

“From a clinical trial perspective, if the 7 goes down to 4, and the 5 goes down to 3, I know both of them got better,” he said.

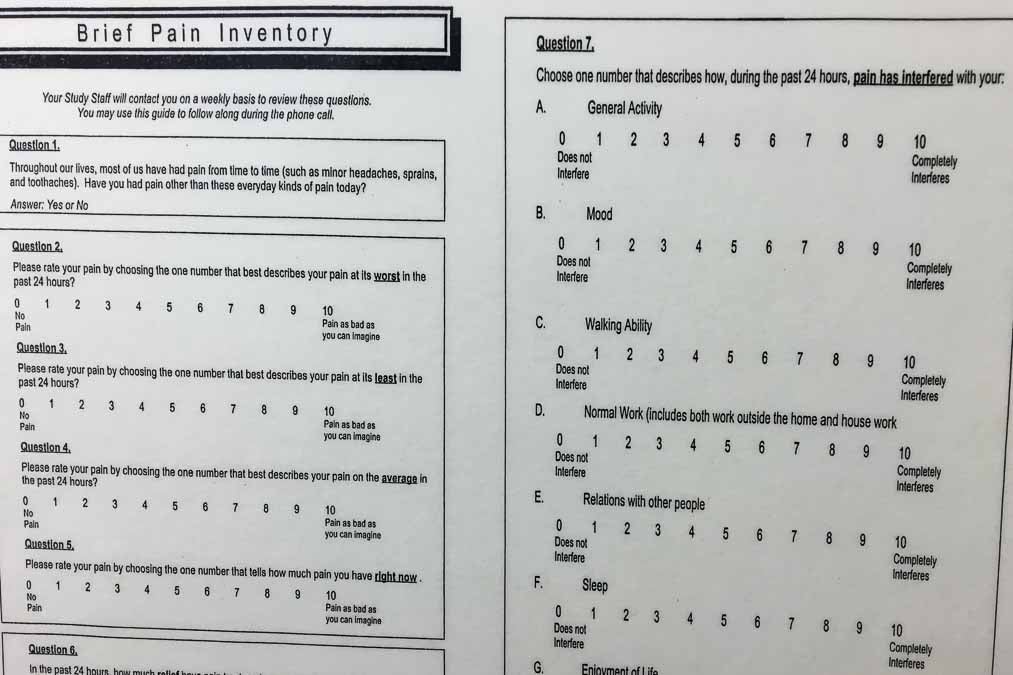

For his research and care of cancer patients, Farrar keeps what’s called the brief pain inventory scale nearby. It’s still brief, but has a lot more questions, covering pain experiences over time and how it interferes with one’s life, that patients respond to on a scale of 0 to 10.

The front page of the Brief Pain Inventory, an assessment tool that Dr. Farrar turns to a lot in research and patient settings. “Instead of just asking how much pain do you have, you need to think about do I mean right now, last week, or forever. And in addition, it’s useful to know if it’s an average pain, do you have the pain all the time? Or, what is your worst pain?” (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

But even surrounded by all of these scales, Farrar says a number in itself can’t be taken as an objective measure. Because in all of these assessments, pain is still self reported.

Your ‘8’ might be different from my ‘8.’ And a lot of factors can influence how a person experiences short and long term pain, factors which scientists are still struggling to understand.

“Any scale that we would used to measure that person’s pain is going to go up and down in relation to things that don’t necessarily have to do with a nerve being pinched or arthritis being worse,” he said. “It has to do with the way people perceive pain, you can’t get away from that. It’s a subjective experience. So part of the problem with pain scales is no matter how good they would be, they’re not adequate to make their own complete assessment about someone’s pain.”

And one pain measure one won’t find in Farrar’s office, is a blood test.

“And in fact there aren’t any tests,” he said. “We now have functional MRI scans where we can look at people’s brains as they experience pain and as they experience relief from pain from treatments,” he said. “And we can tell you what parts of the brain turned on and off, but at this point I can’t differentiate the amount of pain someone has. All I can tell you is the frontal cortex paying attention, sensory system, but can’t tell it how bad for you.”

Limited tools and education

A few hundred yards away from Farrar’s office, the University of Pennsylvania’s emergency room confronts these challenges daily. Pain intensity on a scale of 0 to 10 has become a central part of the electronic medical record. There’s a special slot to enter a patient’s 0 to 10 pain intensity number. There’s a space for comments, too.

Many people come in with a 15 out of 10.

“We’ve all seen the greater than 10 on the 1-10 scale,” said Dr. Jeanmarie Perrone, an emergency physician and medical toxicologist.

But it’s not an option to write that in, added triage nurse Megan Scott.

“You just try to explain it even better and try to refocus,” she said.

Dr. Perrone, who is involved in regional and national opioid prescribing groups, can’t imagine a world without the numeric pain scale. But she and some others worry that its widespread promotion, and more specifically, the way in which it has been used to reduce intensity of pain, has had an unintended outcome. Because measuring and assessing pain, brings with it an expectation to treat that pain, to lower that number.

“I think the leap we’ve made is that we need to get that pain down to 0 or 5, and in various times we’ve never had good guidance in how to decrease the pain and what our endpoints were,” said Perrone.

Perrone says doctors she knows have felt pressured to use what limited tools they’ve had to reduce pain, and opioids have been a big one. These drugs do have an important place in treating certain kinds of pain for certain patients, but she worries that lacking other options or proper training, they have been inappropriately applied.

Around the launch into that decade of pain 16 years ago, federal and international agencies issued more proactive opioid treatment guidelines. Groups like the American Medical Association have contended that new formulations at that time, boosted by manufacturers, convinced the world that these drugs were safer and less addictive for treating long term pain, beyond its more studied use in cancer patients. Meanwhile, pain became a part of patient satisfaction measures and reimbursements, especially with the onset of the Affordable Care Act.

Reassessing the assessment of pain

Dr. Chester ‘Trip’ Buckenmaier, director of the Defense and Veterans Center for Integrative Pain Management, says there’s now a realization that the pendulum swung too far.

“We’ve been so focused on intensity to exclusion of these other issues that we’re missing the point with the patient and ourselves, and that pain therapy isn’t necessarilly about getting pain intensity to 0,” he said.

It’s something he calls chasing zero and the expectation to eliminate pain completely. Buckenmaier, who teaches at the Uniformed Services University and is involved in military, veterans and civilian groups looking into this issue, says there’s one problem with this mindset.

“I’m an anesthesiologist, and there’s no one on the planet I can’t get their pain to 0 [with opioids], but they’re not going to be functional,” he said.

In a nation now grappling with addiction, rising overdose deaths and the search for better ways to understand and manage chronic pain, there’s been a lot of finger pointing and back pedaling.

Congress has launched investigations into opioid manufacturers’ practices and ties to medical groups (including the Center for Practical Bioethics). Federal health agencies are revisiting treatment guidelines. They’re retooling pain as a quality metric in hospitals, and reevaluating the role of pain in patient satisfaction scores.

Even the military is reassessing how it assesses pain, giving that 0 to 10 scale a bit of a makeover.

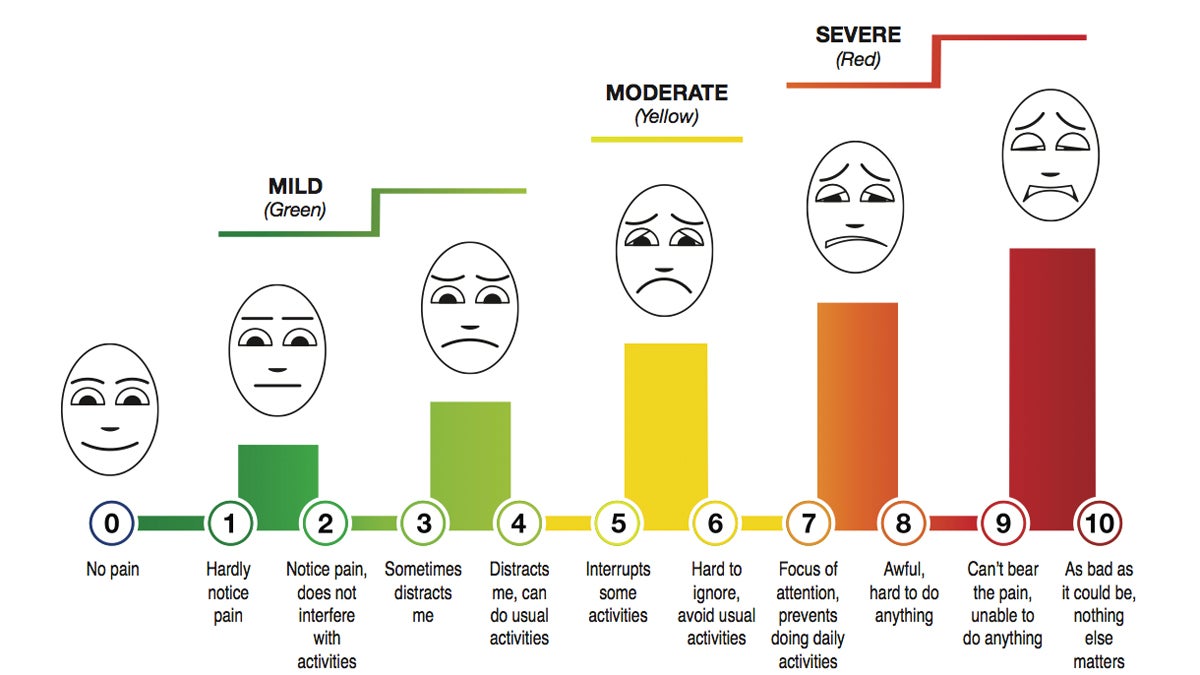

The military recently released this educational video about an enhanced pain scale that they’re rolling out called the Defense & Veterans Pain Rating Scale.

The military is rolling out this Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (Courtesy of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences).

It still uses 0-10, but includes colors, faces and some qualifying language. There’s also questions about mood, stress, sleep and activity. Buckenmaier was part of a group that developed it. He says the scale is just one tool, it won’t solve the bigger problem, but he hopes that changing the way pain is assessed can begin to change the attitudes and approaches to treating it. That’ll involve a lot more than completely getting rid of pain.

“And I think we understand better now that pain is what we call a bio-psychosocial experience, meaning it’s got physical, emotional, and psychological components beyond just that intensity measure,” he said.

It all means that doctors, nurses and patients are navigating a tricky area, trying to find better ways to avoid under treating, over treating and mistreating pain…and at the very least, simply reducing pain down to a single number.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.