‘2001’ came and went, but the movie’s ideas still resonate

Listen 6:44

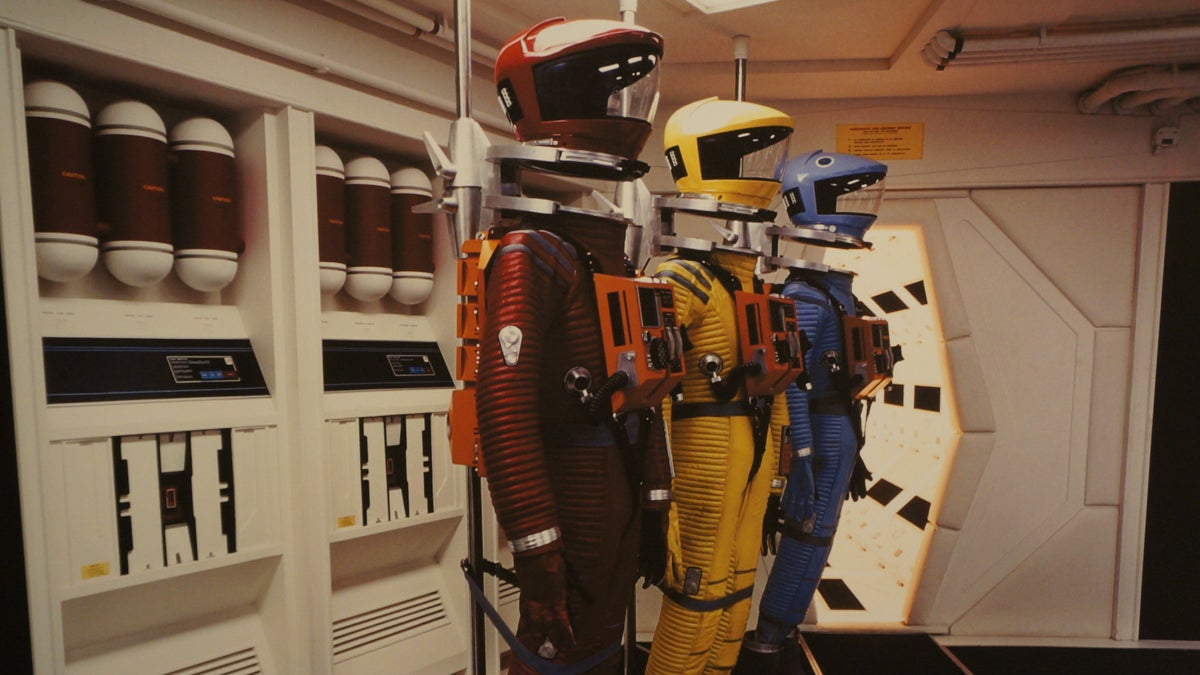

The space suits from '2001: A Space Odyssey' (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

The 1968 movie “2001: A Space Odyssey” painted a grand vision of the future — but for lots of us, the real 21st Century has been a bit of a letdown.

A dad pushes a Porsche carbon-fiber stroller through the park and hands his iPhone to his fussy toddler to keep her occupied. A battery-powered, self-driving car hums past. A quadcopter buzzes overhead, transmitting video back to a hobbyist pilot on the ground. Scenes like this occasionally jolt us into remembering that we really do live in the future. We have so many glowing gadgets, advanced materials, energy-efficient vehicles, and an all-pervasive connectivity that our great-grandparents could never have imagined.

But in a lot of ways, our 2017 world isn’t nearly as cool as the future screenwriters Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke invented for us back in the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

The story is about first contact between Earthlings and a mysterious alien race who have evidently been tampering with human evolution.

In the movie world crafted by film director Kubrick and science-fiction author Clarke, “2001: A Space Odyssey” featured giant rotating space hotels reached on delta-winged Pan Am space planes; a colony on the moon; a nuclear-powered, 140-meter-long interplanetary spaceship; and sentient, talking computers — like breakout movie star HAL 9000.

As a backdrop for their story, Kubrick and Clarke wanted to paint a near future that would seem exotic and inspiring, yet plausible. With financing from MGM, Kubrick hired artists, designers, and model-builders who could observe the ships NASA was actually constructing in the mid-1960s for the Apollo moon program and translate them into visions for the future.

“The film possesses a kind of honorary reality, and its hardware details provide an important historical reference point, not just for film fans but for practicing designers, technologists, and scientists too,” writes Piers Bizony, author of “The Making of Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’.”

“We can look at all the beautiful artifacts in the film and understand a previous generation’s hopes and expectations for the year 2001,” Bizony said.

But here’s the thing: very few of the movie’s technological forecasts came true. We still don’t have commercial space planes, orbiting hotels, or moon bases. In fact, nobody has ventured beyond Earth’s orbit since 1972.

We do have talking computers — Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, and Microsoft’s Cortana — but a few seconds of interaction prove how far they are from being able to think.

Why didn’t we get all the cool things Kubrick and Clarke predicted? How did two people who were so eminently qualified to imagine the future — and who worked so hard to make their depiction believable — venture so far off the mark?

There are quite a few theories to explain this gap. I covered three of them in depth in the pilot episode of my podcast, “Soonish.”

My favorite theory is one that I call “The Carousel of Progress Is Stuck.”

At Tomorrowland in Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom, there’s an audio-animatronic stage show called Carousel of Progress.

It’s a literal carousel, divided into sections that shows scenes of middle-class American family life in the 1900s, the 1920s, the 1940s, and the 21st Century. In each scene, the robot family talks about the modern conveniences changing their lives. Between scenes, as the carousel rotates, the robots sing a goofy song called “There’s A Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow.”

When I visited Tomorrowland with my family in 2016, the carousel broke down, trapping us in the 1940s while the robots repeated their shtick over and over. After about 15 minutes, Disney engineers finally fixed the mechanism, and we rode back to the future.

I now use that experience as a metaphor to sum up an analysis from Northwestern University economist Robert J. Gordon. Gordon’s 2016 book, “The Rise and Fall of American Growth,” argues that technological progress in the United States slowed dramatically after 1970 or so. Since then the worldwide ‘carousel of progress’ has been stuck.

During what Gordon calls the “special century” from 1870 to 1970, the country witnessed a series of innovations of unprecedented depth and impact: electrification, telephony, aviation, urbanization, sanitation, indoor heating and air conditioning, vehicles driven by internal combustion, and the construction of a vast road and highway system to carry them.

“Gordon’s theory is that the big advances from the late 19th century to the 1970s were truly huge things — refrigeration, antisepsis, highways, airplanes,” says Jason Pontin, the former editor-in-chief of MIT Technology Review.

Each innovation contributed to rising productivity and living standards, but each was also a one-time thing. Once the country had been electrified, for example, it couldn’t be electrified again. By 1970, in Gordon’s telling, all the big economic gains from the special century’s innovations had been reaped.

Of course, we’ve seen advances in areas like computing and telecommunications since 1970. But Gordon doesn’t believe they’ve had the same impact on the way people live.

“He thinks that the Internet and personal computers are relatively small things compared to the big stuff,” Pontin says.

If, from our perspective today, the movie world of “2001: A Space Odyssey” looks unrealistic and even a bit naïve, then Gordon’s theory could offer an explanation.

Arthur C. Clarke was born in 1917; Stanley Kubrick, in 1928. Both grew up in the second half of Gordon’s special century.

In 1945, Clarke became the first person in the world to propose the idea of communications satellites that would fly overhead in geosynchronous orbits, relaying radio signals; two decades later in 1963, NASA launched just such a satellite. And as Cold War pressures uncorked enormous spending, the 1960s became an era of dizzying progress in rocketry and space travel.

Kubrick and Clarke watched the first humans fly into space in the early 1960s. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed at the Sea of Tranquility in July, 1969, just 16 months after the premiere of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Throughout Kubrick and Clarke’s adulthood, the industrialized world changed at a pace we would likely find bewildering today. Because of that, their expectations were, understandably, extravagant.

As their movie became a pop hit, the larger culture’s expectations for the future began to shift. With America’s decisive victory in the moon race, the fervor over Apollo abated, and the final three missions were canceled. The nation’s attention turned to the Vietnam War, civil rights, Watergate, an energy crisis, inflation, wage stagnation, and other preoccupations.

“By the time the film [2001] was released, America was no longer quite so sure of its desire to conquer other worlds. The scaling back of Apollo in the late 1960s showed that 2001’s vision of a space-faring culture was becoming redundant at the same time as the film hit the theaters,” Bizony writes.

Here’s my take: even if the pace of progress has slowed since 1970, there’s no reason to think that the technologies portrayed in 2001 are completely out of reach.

In 2013, Pontin gave a TED talk on the question of whether today’s engineers and innovators can still solve big problems, on the scale of defeating fascism in the 1940s or going to the moon in the 1960s. And while at MIT, he created a conference called SOLVE, where technologists and policymakers meet to work through challenges in fields like energy and manufacturing.

“In one sense, I’m very optimistic,” Pontin says today. “We have very powerful tools that could be employed to grow wealth, solve big problems and expand human possibilities. There are smart people in extraordinary universities and in corporate research centers and at places like Google X who are powerfully committed to addressing these great challenges of the day, these civilization-scale problems. We have the tools!

“But there also needs to be a new feeling of our common humanity, that we want to go and solve these problems. We have to want the future…There aren’t fewer smart people, and we haven’t become less good as, as human beings. What we’ve lost is our belief in our collective humanity.”

Judging from the sweeping, three-million-year vision in “2001: A Space Odyssey,” Kubrick and Clarke believed in this collective humanity. And if Pontin is right that the slower progress we’ve experienced since 1970 is more like a pause than a finale, then perhaps the film’s predictions might still come true—just a bit behind schedule.

Editor’s note: WHYY’s “The Pulse” adapted this story from the “Soonish” podcast episode “How ‘2001’ Got the Future So Wrong.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.