Will PA legislators make antidote for heroin overdoses available?

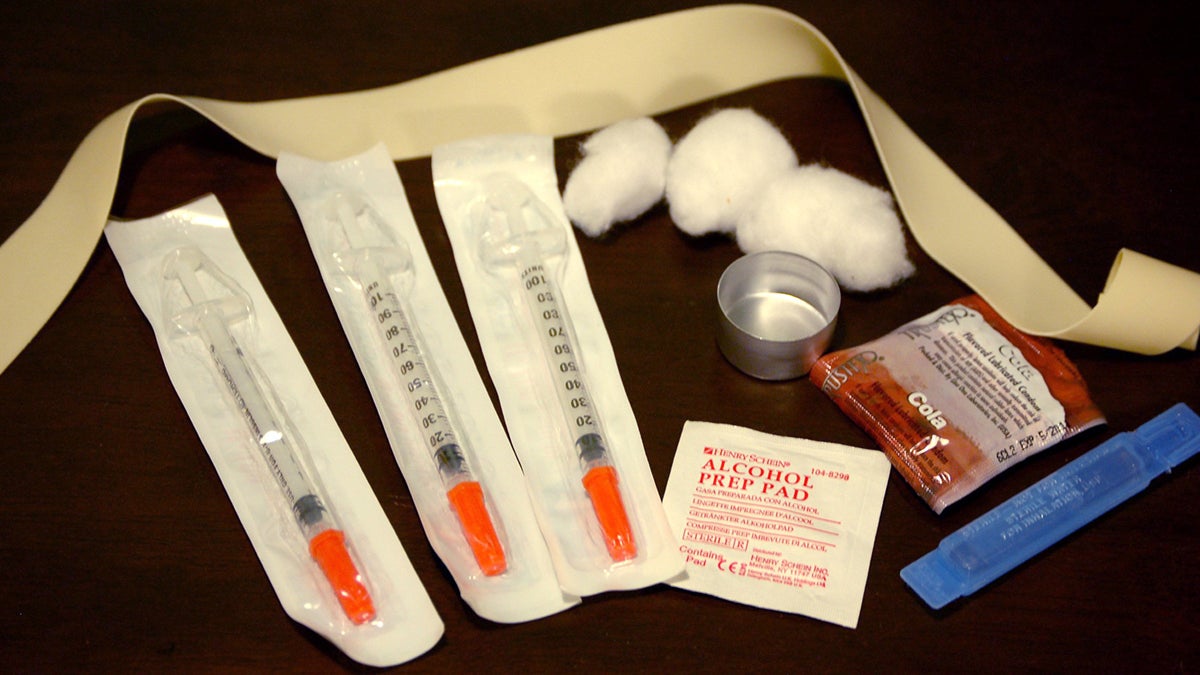

(Photo by Todd Huffman, Flickr/PublicSource)

As a brutal heroin epidemic sweeps the country, lawmakers in 25 states have responded by making it easier to get an antidote to deadly overdoses.

Pennsylvania’s neighboring states of Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York and Ohio already have expanded access to the opioid anti-overdose drug naloxone, also known as Narcan. Their hope: That making it more widely available will mean fewer deaths from heroin overdoses.

But Pennsylvania has been slow to act.

Legislation that would increase access to naloxone and protect witnesses to an overdose from prosecution if they call for help has lingered for months in Pennsylvania’s House of Representatives.

Supporters of Senate Bill 1164 hope that will change when legislators reconvene on Monday.

The anti-overdose drug is cheap, non-addictive and easy to use, Dr. Daniel Schwartz, medical director of Emergency Medical Services at Forbes Hospital in Monroeville, told PublicSource. It’s usually administered as a pre-filled injection, but exists as a nasal spray as well.

“This is not a medical question,” he said.

Drug overdoses killed more than 2,200 Pennsylvanians in 2011, according to the most recent statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The numbers don’t separate those deaths by drug type, though heroin deaths are widely reported to have spiked across the state.

In an overdose, heroin and opioid painkillers, such as oxycodone, stop a person’s breathing. Minutes can mean death or brain damage. Naloxone, which was developed decades ago but has only recently gained attention from lawmakers in many states, renders the heroin ineffective.

The problem is that only paramedics in Pennsylvania are authorized to carry the antidote.

State regulations prohibit Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) from giving the antidote, and the law is silent on whether police and firefighters can carry the drug. Most don’t, though they’re likely to be first to arrive on the scene when, and if, help is called.

“The ambulance people are usually the third on the scene,” Rep. Gene DiGirolamo (R-Bucks), whose son is a recovering heroin addict, told PublicSource.

That means the first responders might not be authorized to use the drug that could stop a person from dying.

In June, DiGirolamo added an amendment to Senate Bill 1164 authorizing doctors to prescribe naloxone to family members and friends — including other drug users — concerned that a loved one might overdose.

Currently, doctors typically only prescribe the antidote to the drug user. However, the user would be in no position to administer the drug if they overdosed.

“I’m getting calls from parents all the time, ‘I see this all over the news, can I get Narcan?’” said Alice Bell, overdose prevention project coordinator at Prevention Point Pittsburgh, a nonprofit organization.

The drug, she said, is not complicated to use and can be injected by children as young as seven.

A son who was an addict

In December, SB 1164 passed the Senate unanimously to grant immunity from prosecution for low-level crimes if a witness to an overdose calls for help. It was then amended without opposition by the House Judiciary Committee to include a provision allowing trained police and firefighters to carry naloxone.

DiGirolamo’s amendment to make naloxone available to the general public was approved 177-26 in the House.

In an impassioned floor speech, DiGirolamo said his son nearly died from an overdose during his five-year heroin addiction.

Had naloxone been available, DiGirolamo said he would have been first in line for a prescription to keep it in his house “in case I woke up in the morning, and he was up in the bedroom with a needle in his arm.”

The amendment is not controversial, though two key lawmakers — Majority Leader Mike Turzai (R-Allegheny) and Speaker of the House Sam Smith (R-Armstrong, Indiana and Jefferson counties) — opposed it.

Steve Miskin, a spokesman for both lawmakers, would not comment on their reasons for voting against the amendment.

Erik Arneson, policy and communications director for Sen. Dominic Pileggi (R-9), the bill’s original sponsor, said he was unaware of any current “issues of substance” that would threaten the bill.

Turzai, who sets the agenda in the House, put the bill on the House’s upcoming calendar. However, he does not have to call bills on the calendar up for a vote.

For the bill to pass, the House must approve it by a majority vote. Then it must be approved by a majority of the Senate.

‘Good Samaritan’ protection

There is a similar bill in the House, but the Senate bill is further along and has nearly identical language on naloxone.

But Bell and others note that the House bill has stronger Good Samaritan protection for drug users. It protects them specifically from arrest if they call for help while someone nearby overdoses.

Even the threat of jail could be a deterrent for drug users to report someone else’s overdose.

“As long as people perceive that they’re going to be arrested, they’re not going to call,” said Bell, who assisted with the House bill.

At this point, though, Bell said that a weaker Good Samaritan provision will have to suffice because heroin deaths are rising, and increasing naloxone access is important.

Future challenges

A new law won’t necessarily mean an instant reduction in deaths.

For that to happen, police and firefighters need to actually carry naloxone — not just be allowed to — and doctors and the public must know that the rules have changed.

“Passing the law is obviously important, but that’s really kind of the first step,” said Corey Davis, Deputy Director of the Network for Public Health Law, who assisted with the House bill.

Schwartz, who is an expert in emergency medicine, said one battle is getting police to agree to carry naloxone. Police and their unions may resist new responsibilities.

“People will fight it,” said Schwartz.

The bill also calls for the state to create training protocols, which he said could lead to further delays before some police and firefighters carry the antidote.

But some police are ahead of the trend.

State law does not actually prohibit police from carrying naloxone, and Schwartz recently trained Pitcairn police in Allegheny County to carry it.

Western Pennsylvania, he said, has a problem with narcotics, and the drug of choice is heroin.

More departments don’t already carry naloxone, Schwartz said, because relatively few doctors in a position to supply it to law enforcement are knowledgeable about the drug. And there must be buy-in from local police.

If a bill doesn’t pass in the session’s remaining days, lawmakers will have to start from scratch in January.

Meanwhile, months will drag by while drug users in Pennsylvania are at risk of what Bell calls preventable death.

“I think that would be a crime,” she said.

Reach Jeffrey Benzing at 412-315-0265 or jbenzing@publicsource.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.