What happened in Flint could happen anywhere

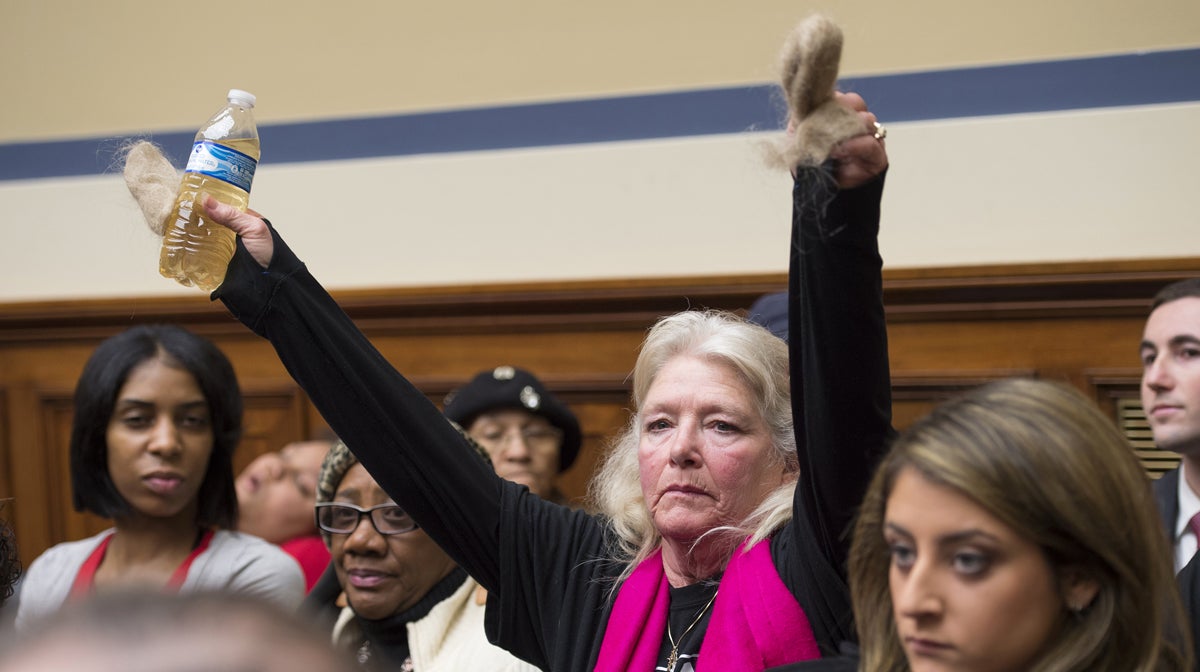

Glaydes Williamson of Flint, Mich., holds up a bottle of Flint water and handfuls of hair on during testimony at the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee hearing on Feb. 3 to examine the ongoing situation. (AP Photo/Molly Riley)

What happened to Flint, Michigan, is a disgrace. While Philadelphia does not have the issues of negligence and incompetence that was displayed in Michigan, that doesn’t mean the city or surrounding areas are safe.

What happened to Flint, Michigan, is a disgrace.

It’s the type of thing you often associate with an impoverished, third-world nation, not a country that boasts loudly that it is the “Greatest Nation in the World.”

Flint’s water crisis, which exposed the city’s nearly 100,000 residents to lead poisoning, was brought about by a malignant combination of arrogance, apathy, negligence, and incompetence. It has exposed a state administration, supposedly built on transparency and “run like a business,” as being more interested in propaganda and PR than the health and well-being of its residents.

For an American city in the 21st century to have thousands of children — a majority of them poor and black — drink and bathe for nearly 18 months in water with a lead count equivalent to toxic waste is incomprehensible and a damn embarrassment to this country.

As a journalist with nearly 12 years of professional experience, I’m supposed to carry myself with some level of objectivity. But this is personal.

I once worked in Flint for a year. I have friends and former college classmates from Flint. I have covered the city for other news outlets. And my former colleagues at the Flint Journal, along with journalists at the Detroit Free Press, Detroit News, and Michigan Radio, have worked tirelessly to cover the water crisis from the very beginning — contrary to popular belief.

As someone who grew up in Detroit, I’ve seen in my hometown what happens when government officials, elected and appointed, fail miserably. Detroit and Flint, merely 80 miles apart along I-75, are not much different from each other. Both cities were built upon the auto industry; both are majority black; both have staggering rates of poverty.

Detroit is currently dealing with the failings of state and local government in the aftermath of the country’s largest municipal bankruptcy, and its long-neglected and embattled school system careens toward insolvency. So in many ways, I feel Flint’s pain, because it’s a pain I experienced up close.

What happened to Flint is a disgrace.

Willful ignorance

People of all ages in Flint are suffering from a number of health issues due to the contaminated water, including skin rashes and hair loss, potential cognitive damage in children, and potential miscarriages in women. But this didn’t need to happen.

People of all backgrounds — parents and teachers, business owners and civic leaders, young and old, black and white — demanded answers from their state and city as to why their tap water was coming out brown and with a terrible odor, only to be repeatedly told that everything is safe. Never mind that in October 2014, General Motors deemed the water coming from the Flint River, the municipal water source, “too corrosive” to use on its auto parts.

Former Flint Mayor Dayne Walling, who repeatedly insisted that everything was fine, appeared on Flint’s CBS affiliate WNEM on July 15, 2015, and brazenly drank a cup of Flint water, saying that all he could taste was “a little chlorine.”

Walling, much of whose power was nullified by state-appointed emergency managers, eventually said that he was given “bad information” about the contaminated water, but his admission couldn’t save him. He lost his seat to current Mayor Karen Weaver last fall. But Walling is far from the only person to look foolish in this affair.

A group of researchers from Virginia Tech found evidence that lead in the water was a major issue. Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, a pediatrician at Flint’s Hurley Medical Center, at the behest of residents, conducted research that found a spike in lead levels in children. Their findings were met with skepticism and even ridicule by state officials who claimed that they were just trying to turn the issue into a “political football.” The Virginia Tech researchers were dismissed by former Michigan Department of Environmental Quality spokesman Brad Wurfel.

Wurfel told a New York Times reporter that the Virginia Tech team was known to “pull that rabbit out of that hat everywhere they go.” It turns out that rabbit was actually a lion, but the state refused to hear the roar until it was too late.

The city also saw a spike in the water-borne illness Legionnaires’ Disease that coincided with the supposedly cost-saving switch from Detroit’s water supply to the Flint River. There were 87 cases of the disease in Flint between 2014 and 2015. The normal average is six cases per year. When the CDC got wind of the 2014 outbreak, they voiced their concerns to the state of Michigan which did not seem to be in a big hurry to address it.

“We are very concerned about this Legionnaires’ disease outbreak,” Laurel Garrison of the CDC wrote to Genesee County health officials in an April 27, 2015, email obtained by the Detroit Free Press. “It’s very large, one of the largest we know of in the past decade, and community-wide, and in our opinion and experience it needs a comprehensive investigation.”

Garrison later added that she was unable to fully recommend what to do about the issue because the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and the city’s water department — which was run by the state — was not providing the county with any information. It was later revealed that Liane Shekter Smith, the former head of the Office of Drinking Water and Municipal Assistance for the DEQ, was more concerned about a potential announcement that Flint’s water was the source of the disease.

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder finally revealed the Legionnaires outbreak on Jan. 13, claiming that he had just learned of it days earlier. However, emails obtained by Progress Michigan show that Snyder’s office was first told of the outbreak on March 13, 2015 — a full nine months earlier.

Following last month’s State of the State Address, Snyder agreed to release 300 of his work emails related to the crisis. Due to a 1986 law, Michigan is one of just two states whose Governor’s offices are exempt from Freedom of Information Act requests.

More emails from Snyder’s staff were released on Thursday evening, which reveal that they knew as earlier as Oct. 2014 that there was an issue with the Flint River’s water and a pair of staffers openly lobbied for it to be switched back to the Lake Huron-Detroit system.

“As you know there have been problems with the Flint water quality since they left the DWSD [Detroit Water and Sewerage Department], which was a decision by the emergency manager there,” Valarie Brader, Snyder’s then-deputy legal counsel and senior policy adviser, said in an email dated Oct. 14, 2014. Brader, along with then-chief legal counsel — and Flint native — Michael Gadola, said that the state needed to switch back to the Detroit system, with Brader calling it an “urgent matter to fix.”

Gadola called the switch to Flint’s water “downright scary” and added in a seperate email that Flint “should try to get back on the Detroit system as a stopgap ASAP before this thing gets too far out of control.”

So, you might be wondering how, knowing this, the word didn’t get out to the public sooner and this wasn’t reported to the DEQ. Well, like with nearly everything else associated with this crisis, the effort to keep it quiet seemed to trump addressing it responsibly.

“I have not copied DEQ on this message for FOIA reasons,” Brader said, noting that the DEQ was subject to FOIA and apparently not wanting to risk the chance that any reporters or the general public to get a hold of this information. It would be nearly 15 months before the state officially acknowledged the crisis in earnest.

What happened to Flint is a disgrace.

‘You don’t know until you know’

Jamie Gaskin, the CEO of the United Way of Genessee County, has been working night and day, seven days a week, ever since the water crisis started. Gaskin says he’s hopeful that by April or May some of the problems with the water will start to ease because of changes in the water system and the city’s infrastructure.

“The hardest thing for people that are working in the response area is that some of us have been on working 28 or 29 [consecutive] days, seven days a week,” Gaskin said. “I’ve really just hit a wall, but there are literally hundreds of people working on this thing every day, and once you get into the day-to-day of it, and you have that many days extended, it certainly wears on you.”

The United Way has partnered with Bensalem-based ZeroWater in a project to get water filters to Flint residents as well as getting donations of water from all over the country.

“We’ve been overwhelmed with thousands and thousands of donors, big and small, wanting to make a difference,” he said, his voice sounding both physically and emotionally spent. “At a time where we sometimes feel alone and isolated, when we get this kind of support, we share it with the broader team and say ‘Hey, people are out there and they care’ and let’s get focused on what the end of this looks like.”

But what does the end of it look like? And how could what happened in Michigan serve as a cautionary tale to other parts of the country? Philadelphia, much like Detroit and Flint, has an aging infrastructure, including a number of homes still running water through lead pipes, as well as areas that are deeply impoverished.

While the city does not have the issues of negligence and incompetence that was displayed in Michigan, that doesn’t mean the city or surrounding areas are safe.

“The Flint water crisis was a huge wake-up call for the nation and should be a huge wake-up call for cities all across the country, especially older cities like Philadelphia,” City Councilwoman Helen Gym said. Newly elected to the council, Gym — along with four other councilmembers — introduced a resolution to hold hearings looking at Philly’s water quality and how to publicly address the city’s aged infrastructure.

“We have tens of thousands of homes that are still dealing with lead pipe issues,” Gym said in an interview on Feb. 5 at her office in City Hall. She said she doesn’t think Philly is dealing with the level of mismanagement and neglectful intent that was behind what happened in Flint. However, she said, “It’s an important opportunity for all of us as a city to revisit the practices that we are engaging in; to understand what the best practices are and what the science is telling us now; and to use this because I think a lot of people are paying attention to it.”

Gym says that, while there have been no complaints about the water — noting most of the lead exposure issues city officials hear about are from lead paint in older homes — this is a chance to educate residents on the importance of infrastructure.

“It’s important for us as a city to understand whether we have programs that are addressing the issue,” she said. “If we don’t, we should develop them; if we do have them, we should be getting them out to the public so more people are taking advantage of it.”

Gym, a longtime advocate for school reform and education, sees protecting children from lead exposure as a primary focus. She suggests that information getting out to homeowners and renters about how to protect against lead exposure is one part of the hearings. She also wants the city to keep better track of lead exposure and to root out any potential problems.

“It does tend to be a casualty of living in one of the poorest cities in the country, and I don’t think that’s acceptable. What we’re trying to do here is set some benchmarks and move forward.”

For Flint, and the state of Michigan as a whole, the damage done will likely not be measured for years. A generation of kids will have to navigate their way through a myriad of health issues stemming from the exposure.

Bill Schuette, Michigan’s attorney general, has opened investigations with the FBI into the handling of the water crisis. Darnell Earley, the emergency manager who oversaw the Flint water switch and was later appointed to oversee Detroit’s crumbling public schools, hastily resigned from that post last week and is currently trying to avoid a Congressional subpoena.

As for Snyder, who at one point in 2014 was rumored to be a potential GOP presidential candidate, he has been mercilessly heckled in public, pilloried by both Democratic presidential candidates, dealt with a multitude of calls from Flint residents, celebrities, and civic leaders for his resignation, is the subject of a recall petition, and is set to testify in front of Congress on March 17.

The ignominy of allowing a majority black, largely poor city of nearly 100,000 people to be poisoned by lead and Legionnaires’ Disease in order to save some money may make for some rough nights for Snyder, but it doesn’t match what could be coming down the pike for the people of Flint and the state of Michigan.

What happened to Flint was a damn disgrace.

What happens next is simply a mystery.

This story has been updated to include new information released by Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.