Professional musicians celebrate their squeaky Suzuki origins

Listen

Yumi Kendall and her brother Nick play pieces from their first Suzuki lessons. Both leared by the Suzuki method

Violinist Nick Kendall’s first instrument was a box of Wheatena. He would hold the empty cereal box under his chin, like he saw his parents doing.

“My parents attempted to start me at 3 years old, but I didn’t know how to behave like a student,” remembered Kendall, 37, of the trio Time For Three. “At my first lesson I tried to teach my teacher. I was one of these kids that couldn’t stay still for a second.”

His younger sister, Yumi, started playing at 5 years old.

“I have always been a cellist, because under Grammy and Grandfather’s piano was a pawnshop cello,” said Yumi, now assistant principal cellist with the Philadelphia Orchestra. “I was brainwashed into thinking everyone plays an instrument, because everybody in my family plays something.”

The Kendalls grew up in the Suzuki method, a musical instruction system that puts small-scale instruments into the hands of very young children, in both individual and group classes. Instructors take them through a meticulously structured set of songs on their sometimes squeaky instruments.

“Every child the world over who learned Suzuki, we all learned the same music,” said Yumi. “We moved from Cambridge, Massachusetts; to Boulder, Colorado; to Washington, D.C. In each city I got to feel I was part of the same family, because we played the same pieces.”

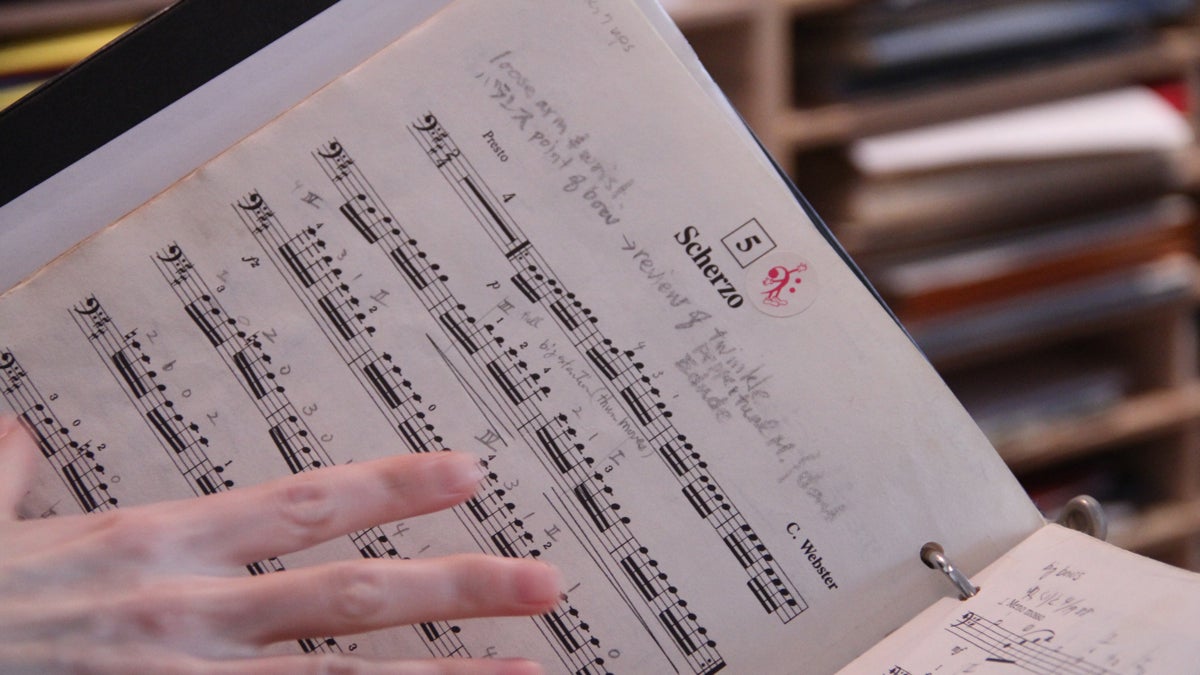

Yumi Kendall points out notes made by her mother in her first Suzuki book. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Yumi Kendall points out notes made by her mother in her first Suzuki book. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The Kendalls have a closer relationship to the Suzuki method than most alumni. Their grandfather — the one with the pawnshop cello under the piano — was John D. Kendall, credited with discovering teacher Shinichi Suzuki in Japan, and introducing his method to America in the 1960s. Since then, millions of kids got their musical start playing the “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star Variations.”

“Yumi and I realized there are so many people out there who want to rejoice over this common bond,” said Nick. “It all has to do with how powerful the method was in shaping who we are today.”

Yumi Kendall launched the Suzuki Alumni Project, a networking website and ongoing series of concerts in which professional musicians give credit to their roots. The first concert, this Sunday at the Trinity Center for Urban Life in Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, will feature several current members of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Neither Shinichi Suzuki nor John Kendall pushed the method as a way to generate child prodigies; rather, it was meant to nurture character in a child. The rigid pedagogical technique is not always appropriate for creating musical artistry. Renowned violinist Isaac Stern once called it “the weakest and most criminal method in music education.”

Nevertheless, as a starter method it has been the dominant form of instruction for generations of classical music professionals. According to violist Gerry Rice, who teaches musical education at the Curtis Institute, the Suzuki method has forged the next crop of musicians.

“The majority of kids at Curtis who grew up in the United States have a Suzuki background,” said Rice.

Rice has been a certified Suzuki instructor for 23 years, and says parents feel more urgent now than ever before about getting their kids hands on instruments.

“The parents that call me and as me to teach are not asking me to make their children pro musicians,” said Rice. “They are asking me to teach their children to love music, to learn discipline, to set goals.”

In 2002, the Kendalls formed a family ensemble (with cousin Daniel Foster and friend Nurit Bar-Josef), called The Dryden Quartet after their grandfather’s middle name. But growing up with the guru of the American Suzuki movement often did not involve music. John Kendall, who died in 2011, had a strong interest in nature. He would rambling around his Toadwood Scrubs, an 11-acre farm in Edwardsville, Illinois. He often invited schoolchildren to directly witness the natural world.

“Only later in life, maybe as a teenager, I started understanding the significance of my grandfather,” said Nick Kendall. “You know, he was just my grandfather. I remember helping him rototill the potato field, building forts in the woods.”

“Although every day at the farm I had to practice violin with him, once or twice a day,” said Kendall. “That was the annoying part. I wanted to play outside.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.