New study: ozone-saving treaty prevented more serious climate disruption

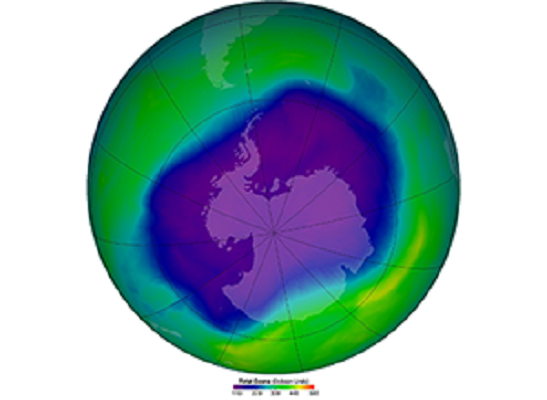

The Ozone Hole Over Antarctica. Credit: NASA

When it comes to discussing climate change, contrarians often throw in historical precedent, reminding people that scientists have been wrong before. That same argument could be made about just about anything.

But there’s a relevant historical precedent – the ozone hole problem.

Stratospheric ozone protects the planet from UV light, and when scientists noticed it was thinning in the late 20th century, they connected the problem to human activity. In that case the scientists thought the problem stemmed from chlorofluorocarbons – CFCs – used as refrigerants and propellants in spray cans. In 1987, CFCs were phased out by international treaty known as the Montreal Protocol.

And now, a new paper in the Journal of Climate makes the case that had we carried on emitting CFCs and the ozone continued to thin, the jet stream and other wind patterns would have been altered, changing the distribution of global rainfall more than it’s already been altered by greenhouse gas warming. Here’s an excerpt from a press release put out by Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

“The ozone layer protects life on earth by absorbing harmful ultraviolet radiation. As the layer thins, the upper atmosphere grows colder, causing winds in the stratosphere and in the troposphere below to shift, displacing jet streams and storm tracks. The researchers’ model shows that if ozone destruction had continued unabated, and increasing CFCs further heated the planet, the jet stream in the mid-latitudes would have shifted toward the poles, expanding the subtropical dry zones and shifting the mid-latitude rain belts poleward. The warming due to added CFCs in the air would have also intensified cycles of evaporation and precipitation, causing the wet climates of the deep tropics and mid to high latitudes to get wetter, and the subtropical dry climates to get drier.”

Some naysayers back in the 1980s thought it was outlandish that human activity could alter our enormous and mighty atmosphere. And some worry that the economic cost of dealing with the problem would render the cure worse than the disease. But look what happened: Not only was the connection to human activity real, but we were able to reverse the trend through an international agreement followed by action.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.