Is our national pastime past its time?

Listen

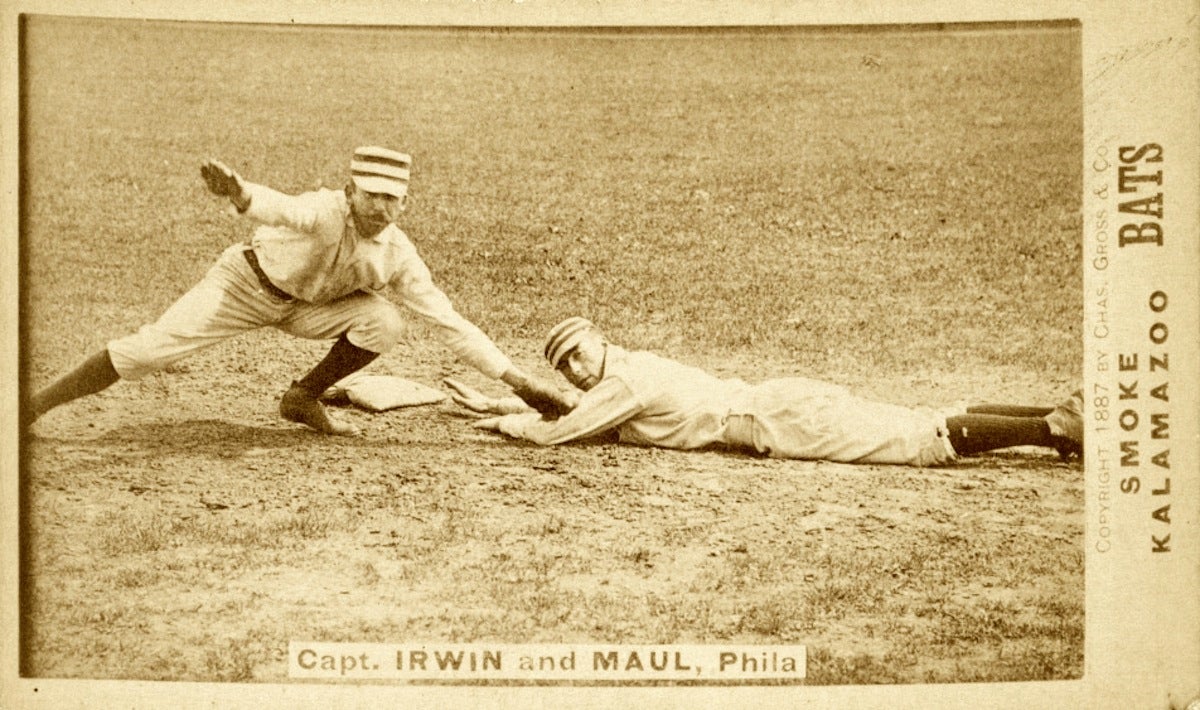

Early baseball card from 1887 showing Arthur Irwin and Albert Maul of the Philadelphia Quakers. The team nickname, The Phillies, eventually became the official name.

Rob Manfred, the new commissioner of Major League baseball, is 56 years old. That makes him a year older than the average television viewer of last year’s World Series.

And that tells you all you need to know about the decline of our national pastime.

Manfred knows it, too, which is why he’s trying to speed up the game. Under the new rules that came into effect last week, when the baseball season started, hitters will be required to stay in the batter’s box — except when time is called — and pitchers will be limited in the amount of time they can spend warming up between innings.

Manfred is also touting MLB’s phone app, designed to appeal to a tech-savvy younger demographic. But no rule change or Silicon Valley gizmo will rescue baseball from its geriatric doldrums. Put simply, our national pastime is past its time.

That’s because baseball — unlike its more popular competitors, football and basketball — is rooted firmly in our agrarian history. It dates to an era when most Americans lived on farms and in villages, not in cities or suburbs. So it doesn’t fit with the frenzied and transient way we live today.

Whereas other sports are played in stadiums or arenas, we watch baseball in places with names like Fenway Park and Wrigley Field. The season starts in the spring — when crops are planted — and ends in the fall, around harvest time. And despite the new time limits on pitcher warmups, there’s no game clock in baseball; you keep working until you’re done.

In other ways, too, baseball has resisted the rigid standardization that marks the rest of modern life. Outfield fences differ radically in distance from home plate, so that a pop fly in one ballpark can become a home run in another. Players use wooden bats specially designed for them, a practice that began in 1884 when a company made a bat at the request of a player in Louisville, Kentucky. (His nickname also became the brand name of the most popular bat, the “Louisville Slugger.”)

Even major league lineups vary from day to day, because of the human limits that baseball imposes. Barring injury, players in other sports can compete in every game. But the best baseball pitcher only takes the mound every fourth or fifth day, so the team’s starting cast is always in flux.

Many baseball players still spend their off-seasons hunting or fishing, two other traditionally rural endeavors that have survived into our urban age. Like these hobbies, baseball requires a mix of patience and attention: you have to wait for long time for the right moment to strike.

And just as expert hunters and anglers often come home empty handed, baseball players become accustomed to failure; even the best hitters succeed just three out of ten times. That helps account for baseball’s culture of superstition, another reminder of its pre-modern origins. The finest singles hitter of his generation, Wade Boggs, believed that eating the same chicken meal before every game improved his chance of success. And many pitchers still won’t step on the white basepath line as they walk from the mound to the dugout.

Until the very recent past, finally, baseball also conjured the mystic bonds that tie us together as Americans. In 1886, Grover Cleveland became the first president to welcome baseball’s champion team to the White House; a quarter-century later, in 1910, William Howard Taft would begin the tradition of throwing out the “first pitch” of the season.

Fans started to sing “The Star Spangled Banner” before each game during World War I, more than a decade before it became our national anthem. And during the next world war, in 1942, Franklin D. Roosevelt sent his now-famous “green light letter” to baseball’s commissioner urging the sport to continue. “Everybody will work longer hours and harder than ever before,” Roosevelt wrote. “And that means that they ought to have a chance for recreation and for taking their minds off their work even more than before.”

Today, most Americans work even longer hours than they did back then. But baseball has lost its patriotic claim on our collective psyche. After World War II, Jackie Robinson’s heroic integration of the formerly all-white major leagues briefly reconnected them to grand American themes of justice, fairness, and equality. But it’s hard to find that kind of national spirit in baseball today.

So Commissioner Manfred should try to revive it, targeting the patriotic passions of contemporary youth. Several recent surveys of our so-called millennials—too often stereotyped as selfish strivers or lazy slackers—have revealed them to be deeply concerned about the state of the country, and profoundly committed to improving it.

They’re especially worried about education and the environment, two areas where our nation has simply forsaken its responsibilities to the future. What if baseball hitched is wagon to them? Both causes would be heavily advertised in every game and telecast. And a fraction of all revenues would go to underserved schools, clean energy, and other related efforts.

From the the designated hitter rule in the 1970s to the new speed-up reforms this spring, baseball has tried to recruit new and younger fans by changing the national pastime. What the game really needs, however, is a new connection to the nation itself. There’s no app for that.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.