Incinerators in Camden, Chester among nation’s most polluting, report finds

Minority communities, like those near incinerators in Camden and Chester, are disproportionately affected by emissions such as lead and particulates, a new study finds.

Delaware Valley Resource Recovery Facility at 10 Highland Ave, Chester, Pa. (Google Maps)

Until very recently, Philadelphia burned its recyclable plastic at an incinerator in Chester, one of Pennsylvania’s poorest communities. The city still sends about 30% of its trash to what are known as waste-to-energy facilities, including the one in Chester.

More than 4 million people in the United States live next to such incinerators, which emit lead, particulate matter, mercury, and other pollutants that can cause several diseases, according to a report published this week by The New School in New York City. Eight out of 10 such facilities are located within low-income neighborhoods, among communities of color.

“We wanted to show the reality of how these dirty incinerators are largely concentrated in environmental-justice communities, which is what community residents and activists on the ground have suspected all along,” said Adrienne Perovich, assistant director at the Tishman Environment and Design Center at The New School and one of the authors of the study.

“And it turns out that 79 percent of the incinerators in the country right now are located in environmental-justice communities.”

Two of the country’s most polluting incinerators are in poor cities near Philadelphia, the study says. The Delaware Valley Resource Recovery Facility in Chester emits more particulate matter than any other such facility in the country, the study says, releasing in 2014 over 200,000 pounds of PM2.5 — very fine particles that are less than 2.5 microns in width. The Covanta Camden Energy Recovery Facility is the second largest emitter of lead among incinerators nationwide, at 380 pounds in 2014, the study says.

Zulene Mayfield chairs Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living, a group fighting against the city’s incinerator. In an interview Thursday, she said the city’s rate of child hospitalization due to asthma is more than three times the state average.

“It’s literally killing people,” said Mayfield. “The City of Brotherly Love chooses not to incinerate their trash within their border, they don’t mind poisoning our children.”

Jeff Tittel, director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, said that if you rub your finger on the window of a house next to the incinerator in Camden, you get silt on it.

“People don’t realize the amount of pollutants that come out of those incinerators — it’s the largest source of lead in Camden,” he said.

Incinerators generate small amounts of electricity and large amounts of pollution, Tittel said.

Joseph Otis Minott, executive director of Philadelphia’s Clean Air Council, agreed.

“Incinerating trash is the most polluting way to deal with waste and emits more harmful air pollution than burning coal or natural gas for electricity,” Minott said in an email.

Currently, Philadelphia sends 28 percent of its solid waste to incinerators. The city’s Zero Waste goal is to reduce that amount to 10 percent by 2035, and to ultimately eliminate the use of conventional incinerators.

“These contracts will expire soon,” Minott said. “Mayor Kenney should not renew them, and instead find solutions to reduce the amount of trash we produce, saving lives in Philadelphia and the surrounding communities.”

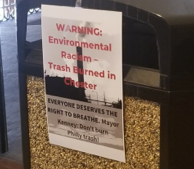

Earlier this month, activists from Energy Justice Network sent Mayor Jim Kenney a letter signed by 40 organizations, demanding that the city stop incinerating its trash. This week, the group began posting signs on trash cans in City Hall, asking that a cleaner contract for the next seven years be brought to a vote in City Council.

The Environmental Protection Agency says that, per unit of electricity produced, the incinerators generate fewer greenhouse-gas emissions than coal or oil, but slightly more than natural gas. And certainly, more than clean-energy sources. As a point of reference, the Camden incinerator produces 21 megawatts of electricity — that’s seven times what the solar panels at Lincoln Financial Field generate in Philadelphia. Still, some incinerators receive federal and state incentives intended for renewable energy.

“And so what we’re doing is really subsidizing the burning of trash and the polluting and poisoning of a community,” Sierra Club’s Tittel said. “This is a failed dirty technology that we need to get rid of. These communities are choking on these incinerators … it’s not only particulates coming out of the plant and the pollution from the plant, but all the trucks bringing in the garbage running through their communities, bringing even more pollution.”

The New School study, funded by the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), says incinerators are bad investments for cities because they’re aging facilities that are too expensive to maintain, too risky to finance, and too costly to upgrade, and they depend on volatile economic and regulatory conditions.

“Instead of spending another $100 million to bail out an incinerator, cities have the opportunity to transition to a system that focuses on reducing waste, creating more vibrant and healthy communities in the process,” Claire Arkin, GAIA’s spokeswoman, said in an email.

As examples of such systems, Arkin mentioned Baltimore’s efforts to build composting infrastructure, and single-use plastic-packaging reductions in California.

Mustafa Santiago Ali, a former Obama administration official for environmental justice, said the study shows that it’s time to move away from incinerators and into clean energy.

“These communities [low-income and communities of color] have been the dumping grounds for the pollution and facilities no one else wants, and have had to literally pay the cost with their health and their lives,” Ali said in an email. “Many of our most vulnerable are literally struggling for a breath of clean air, and that has to be unacceptable in our country.”

Covanta, the company that runs the incinerators in Camden and Chester — among many others in the country — says it complies with regulations so that people living next to the incinerators don’t suffer from pollution.

Paul Gilman, senior vice president and chief sustainability officer at Covanta, said it’s not accurate that the facilities aren’t being operated appropriately.

“They are constantly undergoing maintenance and upgrades to the air pollution control systems, and the numbers are really very, very good,” Gilman said.

The fact that many Covanta incinerators are among what the New School study calls the “dirty dozen” doesn’t mean that their emissions are unhealthy, he said.

“Think about … if you went out in a parking lot with 70 cars and you went to the databases on car emissions and you found the 12 cars that have the highest levels of emissions — you can label them as the dirty dozen cars,” Gilman said. “Now, does that mean that they’re not complying with the rules and regulations that go around emission for both state or federal government? Does that mean that they’re a public-health nuisance? No.”

Gilman said it is the cities that decide where waste facilities are located. Covanta works with the communities providing economic development in Camden and Chester, he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.