An urban garden in Berlin that’s about more than growing vegetables

Prinzessinnengarten has a few cafés, where employees sell food that grows in the garden.(Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

The second in a series of Keystone Crossroads posts from German cities.

I’m spending a few weeks in Germany as part of a German/American journalist exchange program through the RIAS Berlin Kommission and the Radio Television Digital News Foundation. During the trip, I’ll send back lessons on urban planning and revitalization from German cities. Today’s stop: a community garden in Berlin.

Tucked away behind a tall, green fence on Prinzenstrasse street in Berlin, there’s a place called Prinzessinnengarten. It’s an urban garden about the size of a soccer field. And it’s located in Kreuzberg, a neighborhood in a part of the former West Berlin that abutted the Berlin Wall. Kreuzberg has historically had low rents, so it has attracted a lot of immigrants, students and artists. But locals say the neighborhood is changing, and risks becoming less diverse, as rents increase.

The entrance to the garden. (Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

I stumbled across Prinzessinnengarten after coming to Kreuzberg in search of Turkish food (and eating the most delicious falafel of my life). Throughout the day, dozens of people sat in the garden drinking beer, playing foosball, talking, and yes, tending to the plants.

The garden signs list hours of operation, as well as a warning that “unattended children get a free dog and a double espresso.” (Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

In 2009, a couple of Berlin residents formed a nonprofit called Nomadisch Grün (Nomadic Green) and built the garden on a brownfield they leased from the city. The nonprofit’s mission is to educate people about organic food production and sustainable living, as well as to increase biological, social and cultural diversity in the neighborhood.

Nomadisch Grün now has 25 full-time employees. It makes money primarily by selling food and soil from the garden and by providing consulting to other people who want to build gardens in Berlin. The group also gives guided tours and gets a little bit of funding from donations.

Urban gardening is not a new idea in Germany or in Pennsylvania cities. Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Allentown, Reading and other cities all have community gardens.

But Prinzessinnengarten is like nothing I’ve ever seen. First off, it’s more extensive than many urban gardens, partly because it has so many full-time employees devoted to its survival.

Also, the garden is mobile. There are no plants growing from the ground — only in pots, cartons and other moveable containers. That means community members can relocate the whole garden if their lease runs out and the city decides to sell the lot to an organization with deeper pockets.

Many of the plants at the garden grow in plastic crates. (Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

Prinzessinnengarten also has a café and restaurant, where employees sell food made with produce that grows in the garden and at local farms.

(Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

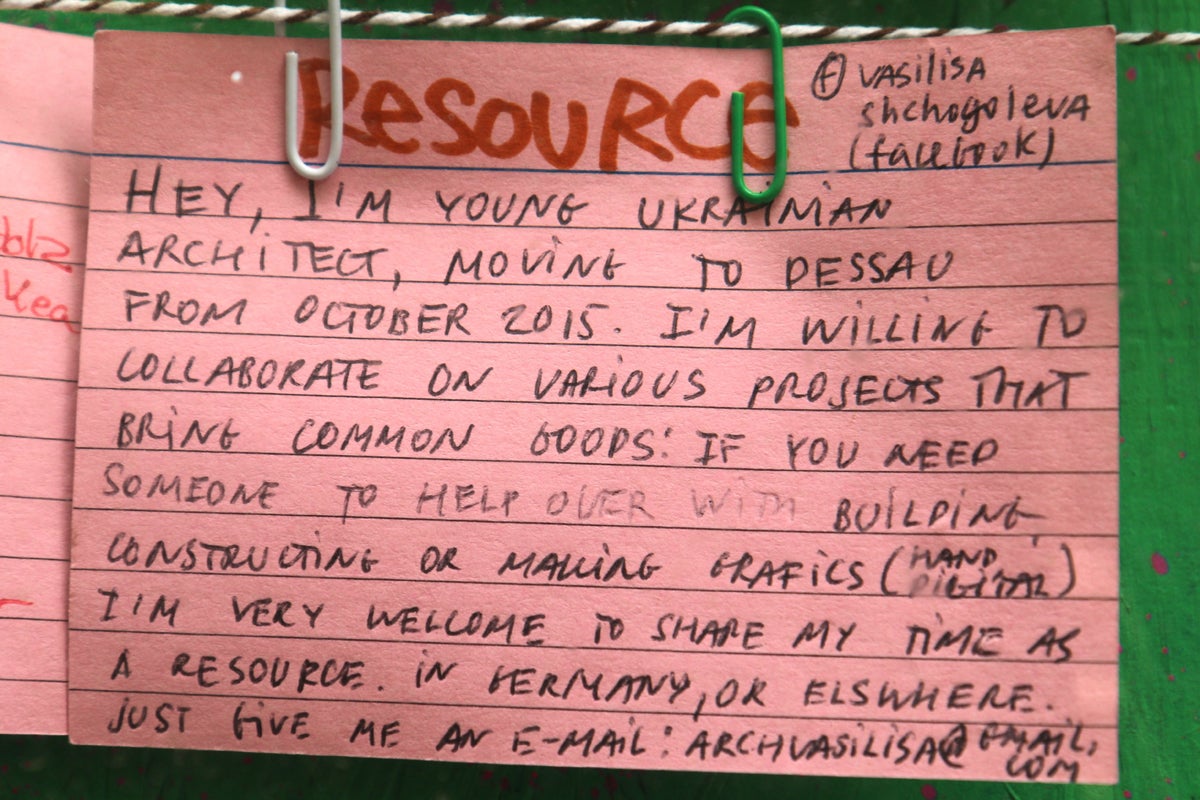

The garden has a “Needs/Resources” board, where community members can fill out an index card if they have a skill to share, or if they need something, like a material or an extra set of hands.

(Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

This person for instance, offers himself/herself as a resource.

(Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

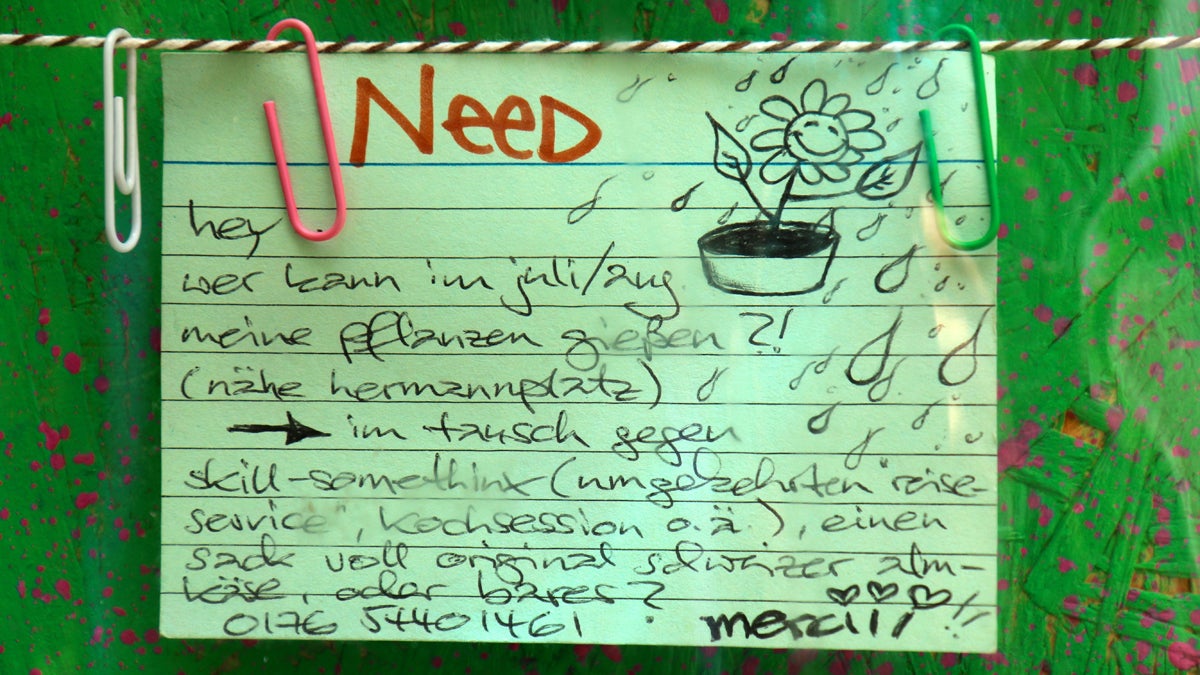

And this person has a need: “Who can water my plants in July/August in exchange for a cooking session or a sack of Swiss cheese or cash?”

(Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

The board is almost like an in-person Craigslist. Taking this kind of exchange off the Internet and into a community space might give these people a chance to interact with each other more than once and even become friends.

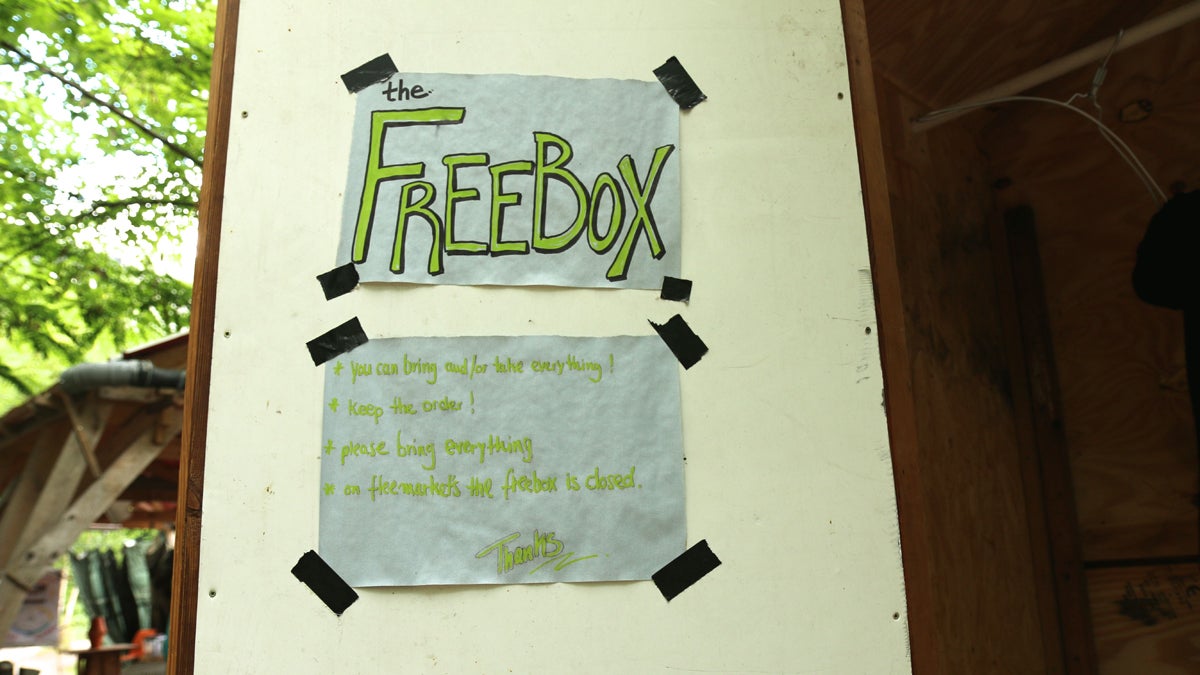

There is also a “Freebox,” where people can leave their old clothes and take clothes if they need them. That’s especially helpful for people who are homeless or struggling financially.

(Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

And there’s communal seating, which is how I met Patrick Marscholl (left) and Maya Metzner.

(Marielle Segarra/Keystone Crossroads)

(Marielle Segarra/Keystone Crossroads)

Marscholl, Metzner and I were all sitting in the “Wurm Café,” which it turns out is German for … “Worm Café.” As in, I was sitting in a bench filled with worms, which allow the gardeners to compost leftover food. It only took a few hours to recover from the shock.

Metzner used to live in the neighborhood. She said the garden was much smaller when it launched in 2009. She remembers parents coming to the lot with their children to plant tomatoes and other plants.

She was surprised to see how much the garden has grown.

Marscholl said the garden has become an urban oasis and a benefit to the community.

Unfortunately, Metzner told me temporary spaces like this one pop-up all the time in Berlin and then disappear.

It’s possible Prinzessinnengarten will disappear when its lease is up in a couple years. As the neighborhood becomes more popular and expensive, the government may want to capitalize on the land’s growing value.

But the garden’s co-founder Robert Shaw said that might be okay.

Moritzplatz, the U-bahn station next to the garden. (Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

As rents in the area increase, the garden still offers free classes and keeps its prices low so that it continues to fulfill its mission. But sometimes “it feels like a shame to offer a meal for two euros to someone who easily could pay 12 or 15 for it,” Shaw said.

It’s possible that the garden might actually be a factor in the neighborhood’s gentrification. Data from the U.S. shows that cleaning up brownfield can increase housing values in a given neighborhood. That jump in value can, of course, push out renters.

In any case, Shaw said he’s not convinced the garden should stay in this particular lot. Nomadisch Grün could always move the plantbeds and other structures to a new brownfield, in a different neighborhood, and continue its work there.

He hopes that if the organization does relocate the garden, it’ll get some support from the city, maybe in the form of an affordable lot or longer-term lease. Right now, Prinzessinnengarten has a five-year lease, but it doesn’t get any other financial help from the city.

Prinzessinnengarten co-founder Robert Shaw (right) plays foosball with a friend. (Marielle Segarra/WHYY)

If Prinzessinnengarten does go elsewhere, it might not look exactly the same.

Indeed, one thing that stuck out from talking to people there was that there’s no one model for an urban garden. Some of the initiatives at Prinzessinnengarten might not be all that useful in Philadelphia or Lancaster.

Still, it was fun getting lost in one of Berlin’s urban gardens and seeing how the community does things. And who knows — maybe seeing Prinzessinnengarten will inspire Pennsylvania residents to try something new. “Worm Cafe Lancaster,” anyone?

You can follow along with the trip through Germany at Keystone Crossroads, @PaCrossroads with the hashtag #kcgermany and on our Facebook page.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.