40 years after Three Mile Island accident, debate over safety of nuclear energy still goes back and forth

Forty years after the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island changed the trajectory of nuclear energy in this country, the debate over its safety and viability continues.

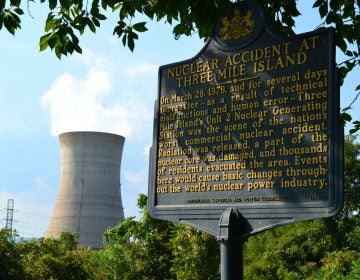

In this May 22, 2017 file photo shown is the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Middletown, Pa.. (Matt Rourke/AP Photo)

This PennLive article appeared on PA Post.

—

Arnold “Arnie” Gundersen was a lead nuclear engineer in 1979 when the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island sent a tide of fear and panic across central Pennsylvania.

Gundersen, a former licensed reactor operator, needed no coaxing to convince a jittery public that it had nothing to fear with regards to the March 28, 1979 accident at the Londonderry Township plant.

“I was on television telling people not to worry,” said Gundersen, whose wife was pregnant at the time. “I was telling everybody, ‘Don’t worry. No radiation got released.’ I think I said, ‘The Titanic hit the iceberg and the iceberg sunk.’ I think that was my comment at the time and boy was I wrong.”

But it took him about a decade to change his mind.

His conversion from proponent to nuclear whistleblower occurred gradually in the 1990s as Gundersen, among other things, served on nuclear energy symposiums and as an expert witness for plaintiffs lawsuits against the nuclear industry.

“I was on the other side of the argument,” said Gundersen, who sits on the board of the Fairewinds Energy Education, a Charleston, S.C.-based anti-nuclear energy nonprofit that advocates for renewable energy. “I would call myself a nuclear zealot back then as opposed to a nuclear critic now.”

Others come at the nuclear energy debate from a decidedly opposite direction.

Kristin Zaitz and Heather Matteson, for instance, were once adamantly distrustful and suspicious about nuclear energy. Like legions of other people behind the anti-nuclear energy movement in this country, they worried about exposure to radiation and the dangers of a catastrophic nuclear plant accident.

The self-described progressive thinking California moms had a change of heart and opinion.

These days, Matteson, who works at the Diablo Canyon nuclear plant in San Luis Obispo County, and Zaitz, who used to work there, are ardent supporters of nuclear energy.

“I realize people need energy for a higher quality of life and the best way to do that is by using resources that are more energy dense,” Matteson said. “Anything we do is going to have an impact on the environment. We have to look at those impacts in context of everything else we care about.”

Forty years after the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island changed the trajectory of nuclear energy in this country, the debate over its safety and viability continues rages increasingly over new environmental concerns – that of climate change.

Nuclear energy is by far the largest source of clean-air energy in the United States, generating more than 56 percent of the nation’s emission-free electricity, proponents note.

“We need to provide people around the world with clean energy,” Zaitz said. “Clean energy in particular. It’s our responsibility for future generations to get out of the way and try to open our minds to all possible options for clean energy.”

The U.S. consumes more energy per capita than any other country in the world. Most of the energy is derived from fossil fuels, which is also the main source used to replace nuclear energy worldwide. Solar, hydro, wind and geothermal electricity sources also are emission-free, but nuclear supplies more electricity than all of them combined, the Nuclear Energy Institute points out.

Matteson said the nuclear energy has been misrepresented and maligned in the eyes of the public, much of it by the media.

“We hear scary news that pesticides are going to kill you. That vaccines cause autism,” she said. “These are all conspiracy theories trying to explain why something bad happens to people. We want to blame it on something and I think radiation is a scapegoat for a lot of people.”

Radiation, she explains, occurs naturally in the natural world, and it would take an inordinate amount of radiation to pose a danger to the public.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission has long stood by its determination that the amount of radiation released in the 1979 Three Mile Island accident was well under acceptable levels and that no member of the public was put in danger as a result.

Now 70, Gundersen, stands by his conviction that the health of untold numbers of people across central Pennsylvania was endangered by the Three Mile Island partial meltdown. Over the years in his testimonies, Gundersen has attested to a litany of factors, he said, contributed to the misrepresentation by the nuclear industry about the facts of the accident, including the number of radiation plumes released, the amount of radiation released and the amount of radioactive waste that was released inside the reactor.

Gundersen said that because of the inaccurate assessments released to the public, subsequent medical studies on the impact of Three Mile Island radiation exposure were compromised.

“The plant wives pulled all the kids out of school by 11,” Gundersen said. “The plant staff knew how serious it was. Civilians, who trusted government, didn’t do a darn thing.”

The 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant disaster in Japan has further fueled the debate on nuclear energy, reinforcing the public opinion chasm. Radiation particles from the plant, which was destroyed that March in the wake of a powerful tsunami, spread over an area the size of Connecticut. About a quarter of a million people fled the area.

Zaitz and Matteson say that experts have determined that the Fukushima accident released far less radiation – and subsequent risks to the public – than initially estimated.

In the wake of the accident, Japan took offline its entire fleet of nuclear plants and turned instead to natural gas and coal as its sources of energy. Japan, home of the Kyoto Protocol, the first international treaty on emissions cuts, and once a leader in the fight against climate change, now ranks among the world’s biggest emissions violators.

“It’s having adverse health effects including killing people every year,” Zaitz said. “It’s affecting far more people who live there than Fukushima ever will.”

A report published by Scientific America in January, noted some areas near the Fukushima plant continue to exceed five times the level of radiation set by Japan as safe for the general public. In certain spots radioactivity remains as high as 20 millisieverts, the maximum exposure recommended by international safety experts for nuclear power workers, according to Scientific America.

The debate goes beyond radiation and certainly includes arguments about uranium mining and radioactive waste. Nuclear proponents say that the mining of uranium levels a far lower impact on the environment compared to fracking, natural gas pipelines and other fossil fuel energy sources.

Gundersen argues that uranium mining exposes workers to radiation, and contaminates groundwater and aquifers.

Citing statistics from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the NEI notes that between 1990 to 1995, states that increased nuclear electricity generation by just 16 percent reduced their emissions by 37 percent. Nuclear power, the NEI says, helps states comply with the Clean Air Act.

Gundersen discredits the assessments released on Fukushima. He claims the nuclear industry used “identical tactics” to deal with that disaster as it did with the Three Mile Island accident, Chernobyl and even the Deepwater Horizon disaster. That includes downplaying the risks and telling the public it is in no immediate danger.

“The industry controls the narrative,” Gundersen said. “The orthodoxy very quickly circles the wagons and protects trillions of dollars of investment.”

Eric Epstein, chairman of Three Mile Island Alert, an anti-nuclear advocacy group, stands behind Gundersen’s assessment of the lack of transparency in the nuclear industry. Epstein says the industry will never own up to the dangers of nuclear energy nor the dangers inflicted on central Pennsylvania as a result of the Three Mile Island accident.

He says he remains resolutely cynical about nuclear: “We can all agree that there are no safe levels of radiation exposure. … But the industry can’t afford to acknowledge the truth. It would bankrupt the nuclear industry.”

Japan has reactivated about seven of its nuclear plants.

Gundersen remains troubled by the nuclear industry.

“It’s an orthodoxy,” Gundersen said. “The nuclear industry is an orthodoxy. What the high bishops say the lowly priests repeat. At the time I just accepted the party line of the orthodoxy.”

For Zaitz and Matteson, co-founders of Mothers for Nuclear, too much is at stake not to stand behind it.

“In col,lege I learned about the biases we all have,” Zaitz said. “I started evaluating my beliefs and using more data instead on a feelings-based approach. I used that to examine beliefs about nuclear…..it aligns with my values about preserving the environment. The ability to use electricity on a tiny footprint with no emissions was something that made me challenge my views.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.