14 things you didn’t know about Philly and World War I [photos]

One hundred years ago this week, the first military actions of World War I were stirring across Europe as Austria-Hungary invaded Serbia, touching off four years of conflict that would usher in the 20th century as we knew it. The United States didn’t enter the war until April 1917, but the war effort began in Philadelphia and other cities before that and lasted long after the last shots were fired on Nov. 11, 1918.

At the time, Philadelphia was the nation’s third-largest city, home to 1.5 million people, and no facet of city life was untouched by the war and its effects. We spent some time digging around the web in the wealth of local archival material and special commemorative collections tied to the centennial. And we talked to Peter John Williams, author of Arcadia Publishing’s “Philadelphia: The World War I Years.”

Here are 14 things you probably didn’t know about Philadelphia and the Great War:

1. When it came time to serve, Philadelphia rallied.

Several local or mostly local military units served with distinction in the American Expeditionary Forces, including the 28th Division (The “Keystone”), the 312th Field Artillery, the 304th Engineers, the 314th Infantry and the 315th Infantry Regiment, “Philadelphia’s Own.”

By war’s end, more than 3,000 Philadelphians would be dead.

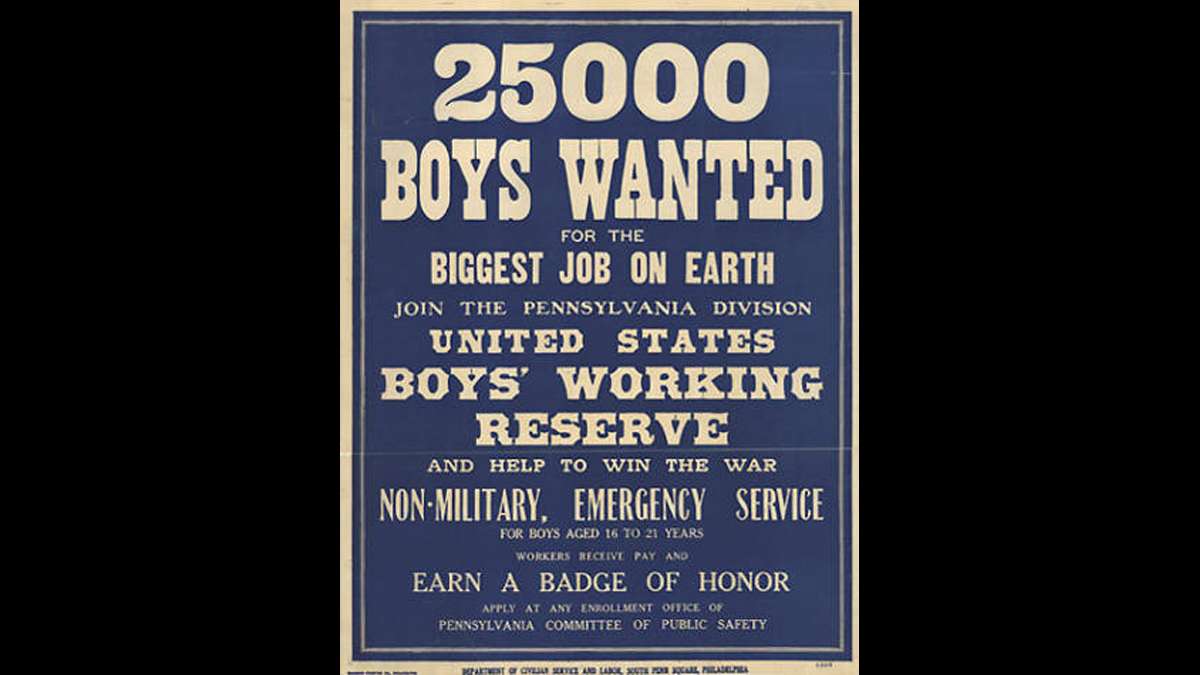

2. Yo — it wasn’t just doughboys.

Miss Loretta Perfectus Walsh (below), age 21, of 732 Pine St., became the first woman to enlist in the U.S. Navy as something other than a nurse. By war’s end, Walsh would be one of more than 12,000 “yeomanettes,” who received the same pay and benefits as male yeomen — nearly unheard of at the time.

More than 2,000 Philadelphia women served in the war.

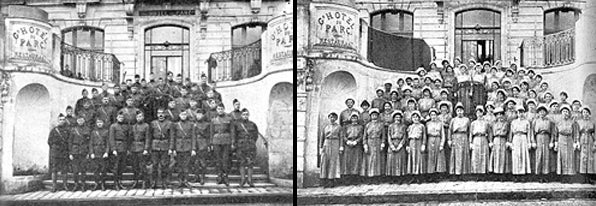

3. Long before the U.S. entered the military conflict, the University of Pennsylvania and other major city hospitals were preparing.

Penn medical professionals organized Base Hospital #20, first on campus, where doctors, nurses and medics were trained before sailing for France in 1918. With 22 medical officers, two dentists, a chaplain, 65 nurses and 53 enlisted workers (many of whom are pictured below), Base Hospital #20 would see 4,000 surgeries and 3,500 medical injury and gassing patients — with only 65 deaths.

Williams noted that the base hospitals organized by Thomas Jefferson, Pennsylvania, Methodist and Episcopal hospitals, among others, “were all put together by private donations — the government didn’t pay for those.”

4. In 1914, Philly was a multi-lingual, multi-cultural city of immigrants.

Sixty percent of Philadelphians were either foreign-born or first-generation Americans, Williams said, and they read the dozens of city newspapers — eight in English, three Italian, two Polish, several German, and others — to keep abreast of events in the old country.

5. The summer of ’14 was a hot one.

Williams keeps a Facebook page chronicling some of the contemporary events of Philadelphia during the war years, and notes this item from July 27, 1914:

Mrs. Margaret Ruggles of 1718 North 12th Street, had her husband William, arrested today to save his life. Mrs. Ruggles feared the excessive heat would overcome her husband at his job which involved working on the roofs of tall buildings. She said the last few days he had come home exhausted and seemed out of his right mind. When police arrested Mr. Ruggles they also found him delirious and transported him to Pennsylvania Hospital where he will be kept overnight.

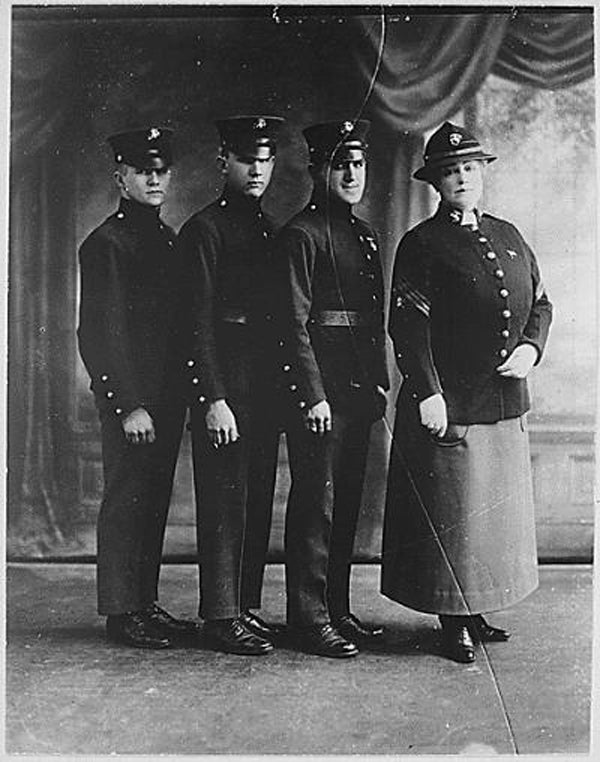

6. At the Jersey Shore, a celebrity sighting.

The stylish actress Lillian Russell (below, right), one of the biggest names of the day, was taken ill with exhaustion and spent time recuperating at a cottage she’d taken in Ventnor. She got better and went on to become the most famous member of the U.S. Marine Corps Women’s Reserve and was said to have “sold as many Liberty Bonds as anyone in the country.”

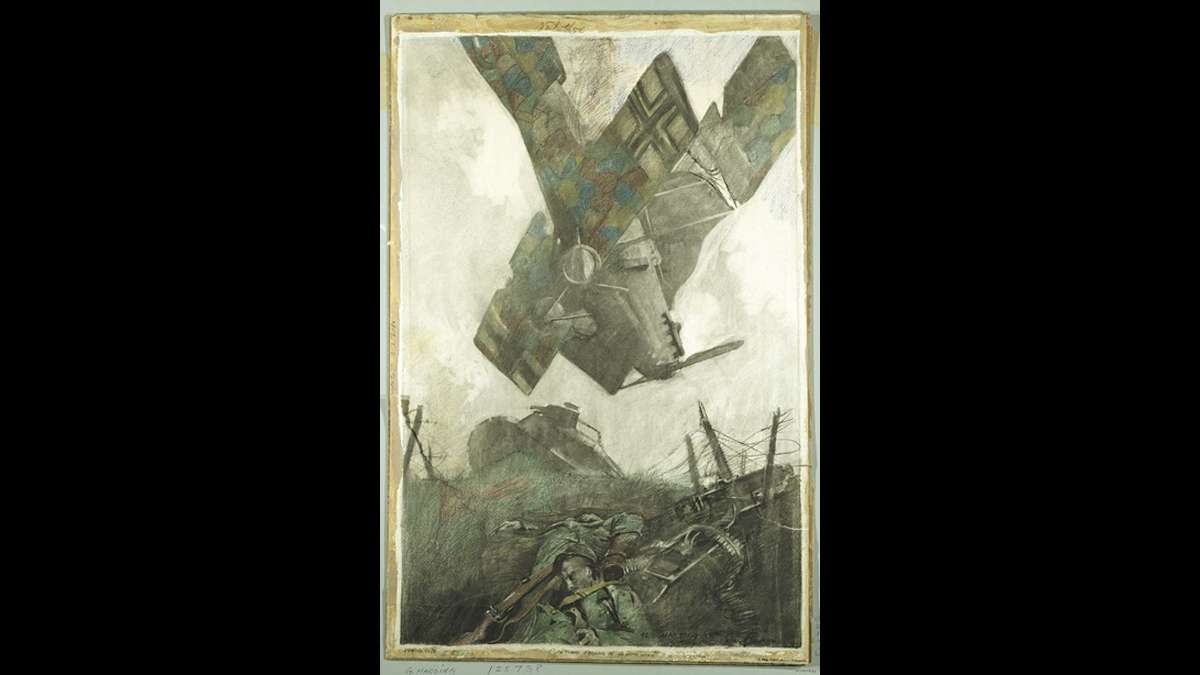

7. Speaking of Liberty Bonds, Philadelphia artist George Matthews Harding helped sell plenty, too.

Harding studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and illustrated recruiting signs for the Navy. He then became one of eight men selected as official U.S. combat artists. The artists were not permitted to actually fight, but their depictions of battle did not spare the viewer the brutality and horror of war. The men completed more than 500 paintings by war’s end, according to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

8. The war’s impact on the arts, from poetry to painting, was profound.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary, PAFA is planning what is being called the first major exhibition of American art related to these wartime years. “World War I and American Art” is planned to open in November 2016.

9. The dogs of war did their bit.

Pat the Mascot was found by the men of the 314th after an attack on Germans and thus, only “spoke” German. Another dog, Philly (below), was a “heroine of the trenches” who served with the 315th. Pat made it home, smuggled against orders on a troop ship by the soldiers who adored him. Philly came home with a sergeant and settled in Frankford, where she had four pups.

Good dogs.

10. Today, Philadelphia has two major World War I monuments, though remembrances can be found in buildings and on public memorials all over the city.

The Tenderloin Doughboy stands at Second and Spring Garden, in what is actually called Madison Memorial Park. But as Hidden City Philadelphia notes, he didn’t start out charging into battle in Northern Liberties — the statue once stood in a pocket park at Fifth and York.

The swirling golden Aero Memorial on 20th Street across from the Franklin Institute was erected in 1950 to salute “the aviators of Pennsylvania killed in action.”

11. The war came during the height of Philadelphia’s heyday as a manufacturing hub, and city factories swung into action.

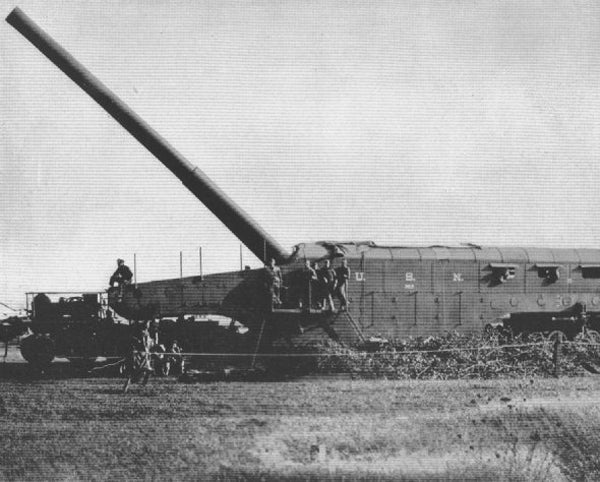

Workers in every city neighborhood made millions of bandages and uniforms. The sprawling Baldwin Locomotive Works on Spring Garden Street retooled and turned out more than 5,000 rail cars before U.S. troops even entered the war, Williams said, while thousands of rifles and millions of artillery shells came out of their plant in Eddystone. Five 14-inch naval guns (below), constructed by Baldwin were in action in France.

The Ford automotive plant at Broad and Lehigh switched to making machine-gun trucks, using automotive knowledge to advance military technology, along with 2 million flat-brimmed steel doughboy helmets.

12. Philadelphia’s society families didn’t hesitate.

Cousins Julian Biddle and Charles J. Biddle joined the French Lafayette Flying Corps together in 1917, Williams said. After only 19 days, Julian was killed in action. Charles racked up service medals from the French and American governments, then went on to a long career as a Philadelphia lawyer. Another society scion, John Armstrong Drexel (below), served in France, both in the French and American air corps. Anthony Joseph Drexel Biddle served in the war, and went on to a long diplomatic career.

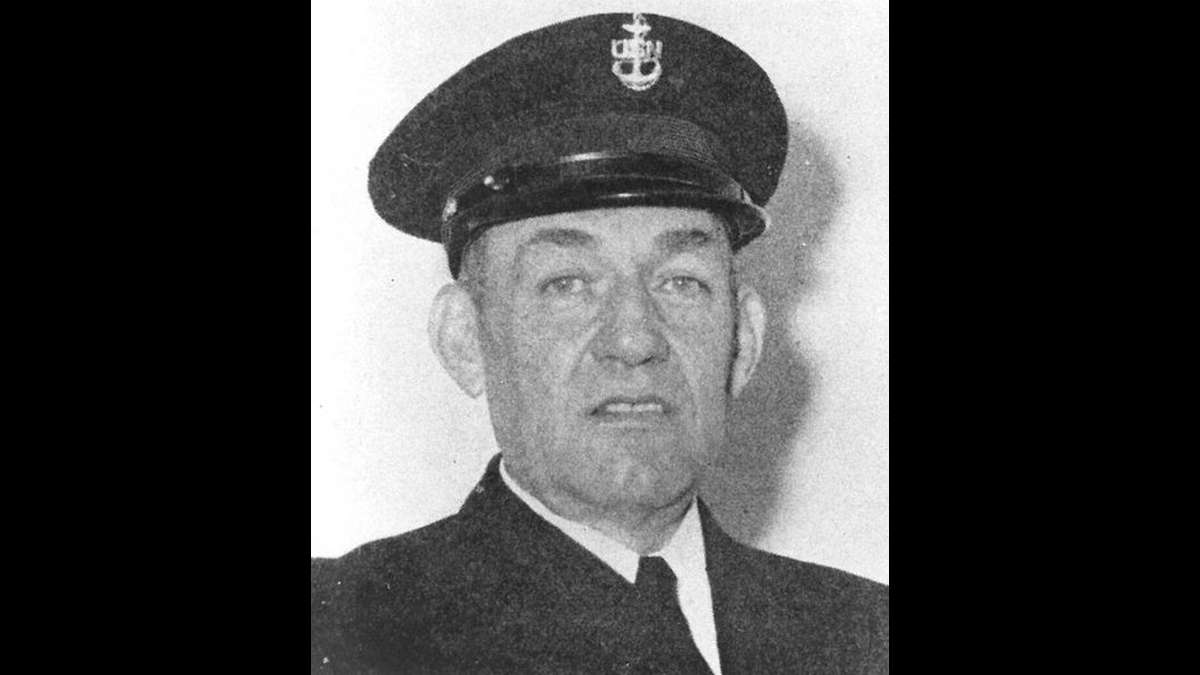

13. One Philadelphian won the Medal of Honor for his service.

Oscar Schmidt Jr., a chief gunner’s mate on the USS Chestnut Hill, was recognized for heroic actions during an explosion and fire on a submarine chaser vessel in October 1918. Schmidt died in 1974 and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

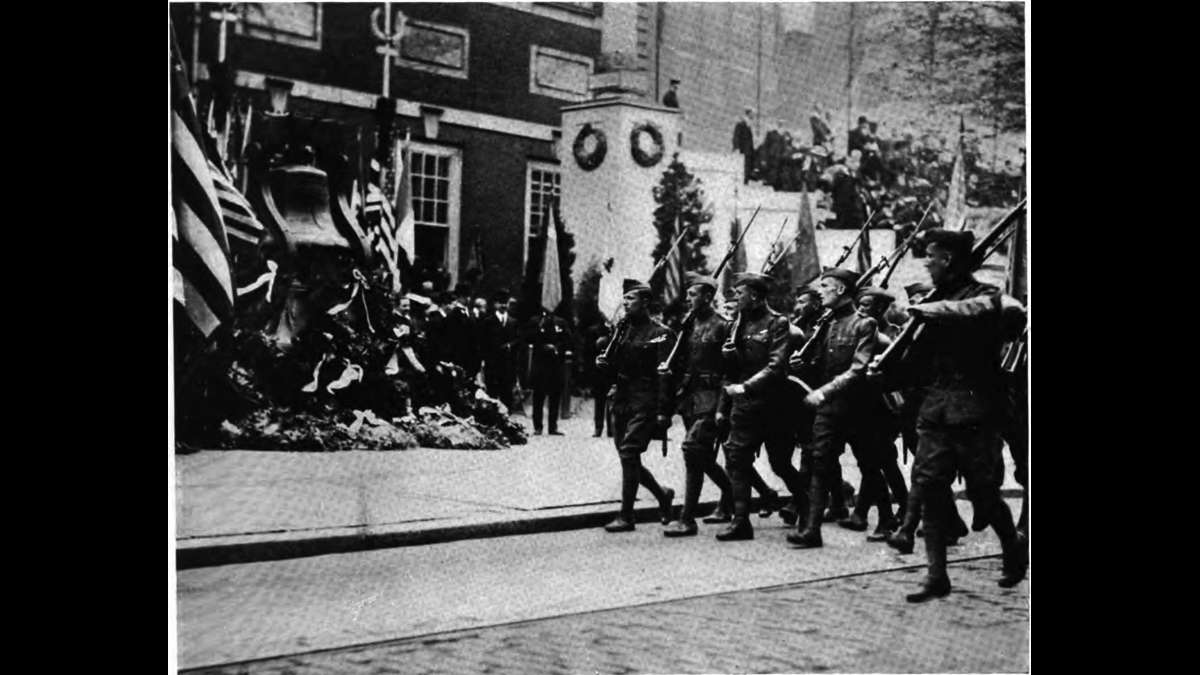

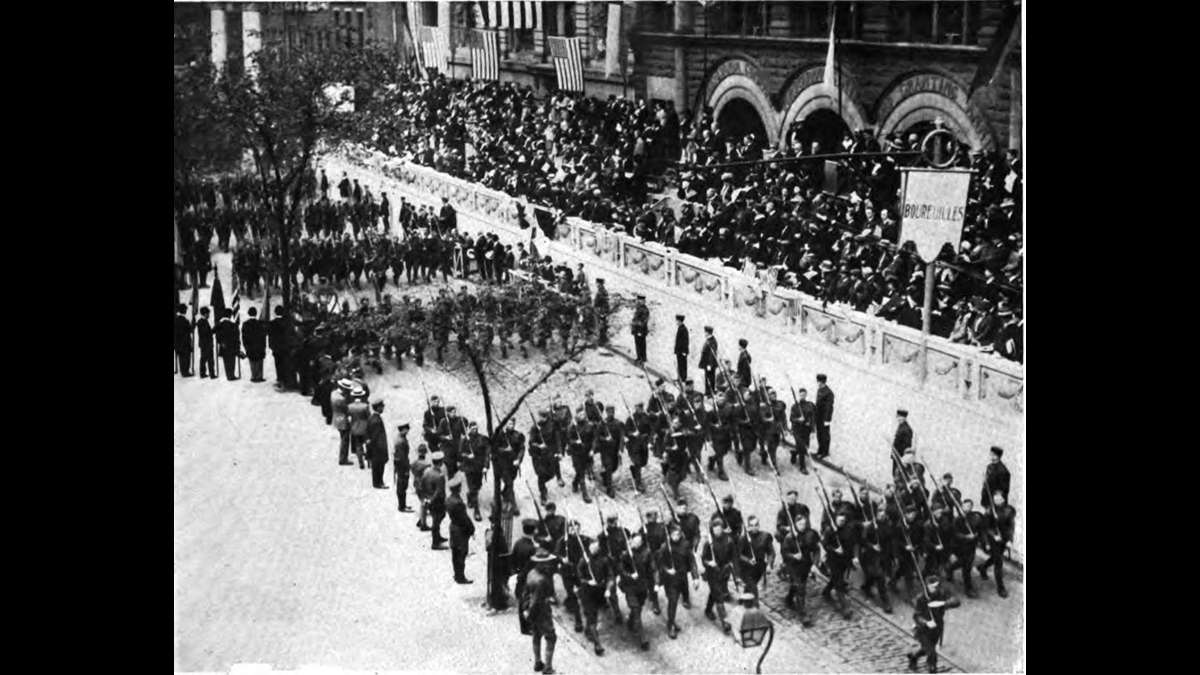

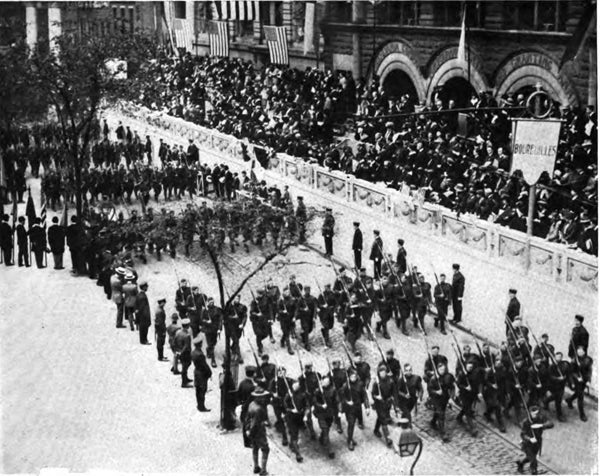

14. When the war ended, the 28th Regiment arrived home first — and Philly threw a party.

Two million people are said to have attended the enormous homecoming parade on May 15, 1919. The parade began at Broad and Wharton and wound its way through the city, ending at Shibe Park at 21st and Lehigh. Inside the park was a massive canteen set up to offer refreshments and entertainment for the soldiers after their long celebratory march.

Along the route were 500 Civil War veterans who turned out along Chestnut Street to salute the returning doughboys, Williams said.

“They were so proud of these young boys, and some of the young guys, from what I’ve read, got misty eyed that these [Civil War] guys were showing them honor,” he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.