Teaching math and science through art, and a neural net (made of children)

Listen

An art installation in the prison yard at Eastern State Penitentiary illustrates the soaring U.S. incarceration rates since 1900. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

In the fall of 2013, Ben Volta arrived at Morton McMichael School with no ideas. He had just been hired by the school in the Mantua neighborhood of West Philadelphia, in partnership with Mural Arts Program, to develop a mural with the students.

He had no lesson plan, no vision of what the mural would be. He came on the first day of class, sat down with the other 7th graders, and listened to the teacher.

“I remember them doing a lot of long division,” said Volta. “I don’t remember how to do that, and I was trying to figure it out as they go.”

Ben Volta directs the painting of a massive mural that wraps around Morton McMichael school in Mantua. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Ben Volta directs the painting of a massive mural that wraps around Morton McMichael school in Mantua. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Like many 7th graders, his mind started to wander. As a kid, Volta was a terrible student, barely earning the marks to graduate from high school, but he always excelled at art. While not paying attention to long division, he remembered a short movie he had once seen called “Powers of 10,” a 1977 short film made for IBM by Ray and Charles Eames – designers famous for the Eames chair.

The film is a visual experiment in representing exponential multiplication. It starts by focusing on two people picnicking in a park in Chicago, and slowly zooms out. Every 10 seconds the field of view expands to the next power of 10. It takes just a few minutes to reach the infinite expanse of the universe.

Painters (clockwise from left) Jason Mattis, R. Craig and Jesse Krimes put the finishing touches on the Micro to Macro mural designed by students at Morton McMichael school in Mantua. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Painters (clockwise from left) Jason Mattis, R. Craig and Jesse Krimes put the finishing touches on the Micro to Macro mural designed by students at Morton McMichael school in Mantua. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Then it zooms back in by the same power of 10, in reverse, quickly finding that couple on the picnic blanket and zeroing into a microscopic level, probing the structure of skin cells.

“It went from the people out the universe, and the universe back to the people, and in their skin cells,” said Khia Smith, one of Volta’s students. “It was weird, is what I’m saying.”

“I remember that. The whole class had that “ewww…wow” factor,” Volta responded. “Everybody liked it, but its was “ewww” when you got in and recognize that is inside all of our skin cells.”

Once you get “ewww” out of 12 year olds, you’re golden. Volta started taking the seventh graders through design exercises that would end of up becoming the mural, called “Micro to Macro.” At the south entrance to the school, the wall is made of exploded molecular imagery, becoming plant cells and trees to the east. As the mural wraps around the corner and moves north, the imagery becomes cosmic with solar systems and planetary orbits.

As Ben Volta’s Micro to Macro mural wraps around Morton McMichael school, wraps around the corner and moves north, the imagery becomes cosmic with solar systems and planetary orbits. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

As Ben Volta’s Micro to Macro mural wraps around Morton McMichael school, wraps around the corner and moves north, the imagery becomes cosmic with solar systems and planetary orbits. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Along the way the students learned about plant biology, the solar system, and vesica piscis – an obscure way to create perfect equilateral triangles by drawing circles with a compass. It’s how the ancient Egyptians built the pyramids.

Volta is not a scientist, and he is not particularly good at math. Nevertheless he is recognized as an excellent teacher of Science, Technology, Engineering and Math – the so-called STEM educational initiative. Add Art to the mix, and STEM becomes STEAM.

“The idea was authentic learning,” said Jerry Jackson, a middle school teacher at Grover Washington school in Philadelphia who had worked with Volta for six years. “It’s using different subjects simultaneously: not trying to teach math, not trying to teach art, but using both in an authentic situation.”

Students are demonstratively better if they learn STEM subjects through art projects, according to Jackson. With the help of grant money, Grover Washington hired Volta to come in once a week to teach art. However, Grover Washington does not have a period of the day set aside for art education. Every week, Volta joined Jackon’s math class to develop a creative project that leveraged math concepts like geometry and basic algebra.

“We would compare the data at the end of the year of the class that completed the project with another class,” said Jackson. “They got the same instruction, but once a week the homeroom class got the art project. Their results were always higher. Year after year – it wasn’t a fluke – it always resulted in improved test scores.”

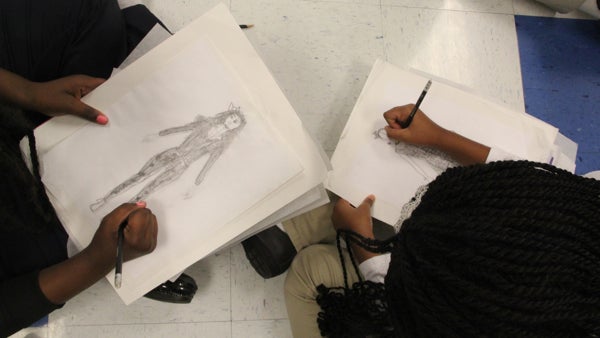

Students at Russell Byers Charter School sketch their designs for costumes representing nerve cells. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Students at Russell Byers Charter School sketch their designs for costumes representing nerve cells. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Volta’s current project, through Moore College of Art, is teaching 5th graders at the Russell Byers Charter School in Center City is about brain cells. He and Heather Ujiie, an adjunct professor of fashion at Moore, asked the kids to draw costumes based on the structure of neurons. Many of the kids drew super heroes with spikey things sticking out of their shoulders.

“Those are not spikes coming out,” said Volta, speaking to the class showing him its work. “Does anybody know what they are?”

A student softly but confidently offered up: “Dendrites.”

“All right. Yeah,” said Volta. “Dendrites. Good.”

Damiyah Webber, a fifth grader at Russell Byers Charter School, takes up her position at the end of a dendrite and awaits instructions during a rehearsal at the Franklin Institute. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Damiyah Webber, a fifth grader at Russell Byers Charter School, takes up her position at the end of a dendrite and awaits instructions during a rehearsal at the Franklin Institute. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

(Dendrites – if you need a refresher – are branches growing out of the axon of the neuron, which pick up electrical impulses from neighboring neurons.)

Volta and Ujiie guided the class to make a single, massive costume fitting all 25 kids simultaneously. Each is an axon (denoted by a bicycle helmet laced with illuminated wire, interconnected by dendrites (denotes by decorated, Styrofoam swimming pool noodles) creating a neural net of ten year-olds.

Students from Russell Byers Charter School act out the parts of a nerve cell during a rehearsal at the Franklin Institute. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Students from Russell Byers Charter School act out the parts of a nerve cell during a rehearsal at the Franklin Institute. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

“Fifth grade is great because they get excited really easily,” said Volta over the din of the class working on drawings. “You bring in color and creativity and they get excited pretty quick. Middle school you have to kick-start a little. High school is its own beast. It’s really challenging to wake them up.”

“We’re working on an axon,” said Andrew Drumwright, 10, sitting on the floor of the Franklin Institution working on his helmet. “The axon is holding the neurons. Right now I’m a neuron. When my helmet lights up, it’s a sign I have an idea.”

Students act out the parts of a nerve cell during a rehearsal at the Franklin Institute. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Students act out the parts of a nerve cell during a rehearsal at the Franklin Institute. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

On Jan. 21st, the class will perform a demonstration of its costume during one of the Franklin Institute’s monthly Community Nights. Some kids, like Drumwright, can explain the basic functions of the dendrite and axon. Other kids are less sure of the distinctions between them.

Whether or not the students grow up to be neurologists – or even remember the distinction between an axon and neuron – is beside the point for Volta. His teaching method is heavy on process: he starts projects knowing very little about the lesson content beyond what his students know. He learns the subject matter along with them, while letting their enthusiasm drive the direction of the project.

Aliajah Higdon portrays the nerve cell nucleus in her class science pageant at the Franklin Institute. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Aliajah Higdon portrays the nerve cell nucleus in her class science pageant at the Franklin Institute. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Volta says the point is to teach kids that learning is a process of discovery, not memorization of facts.

“The idea that it would be lost on them is minimal compared to the experience they had, about thinking about content in a creative way,” said Volta. “I want them to remember we went through this process that brought us to something unexpected.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.