Like chocolate and beauty, good ads light up your brain

Listen

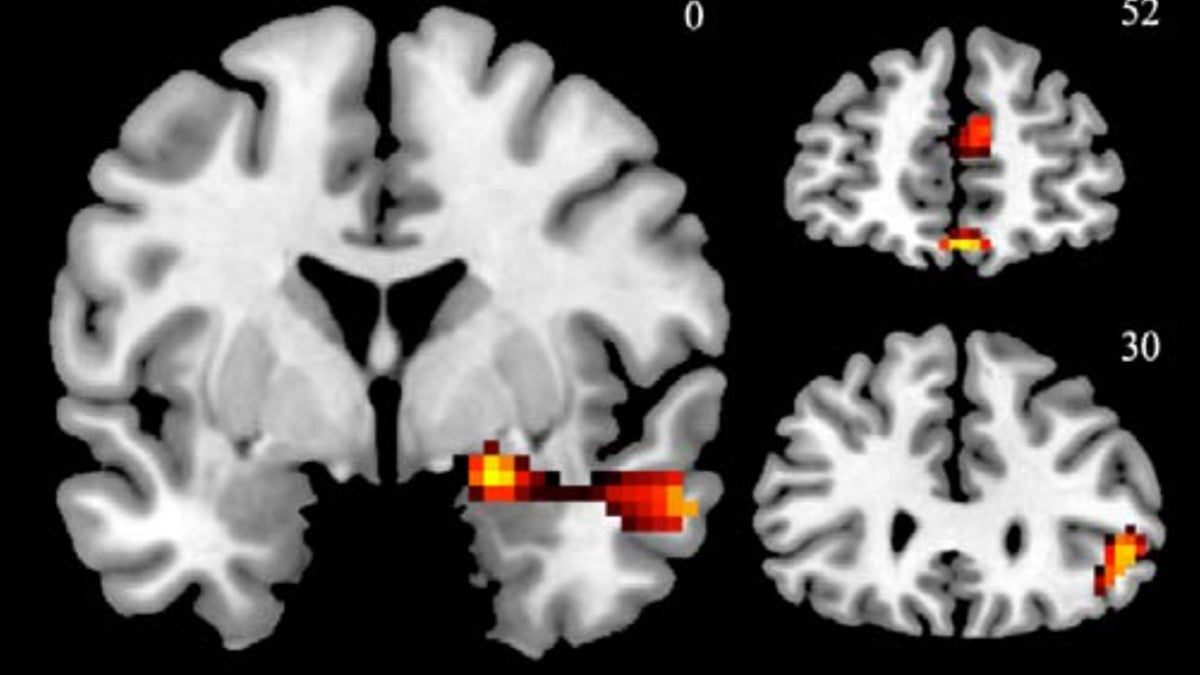

This fMRI image shows activations in the brain

New research explores how the body reacts to successful commercials.

Thirty seconds is an eternity when spent suffering through a bad television commercial.

That’s why marketers and creative types spend lots of time and energy testing ads before they launch. They may want to pay attention to some new research out of Temple University, which finds the best way to predict a commercial’s quality isn’t through traditional focus groups, but instead through the reactions found deep within the viewer’s brain.

“The goal was to try to determine if we can learn something more about what makes an effective commercial, beyond what people say in response to a simple question like, ‘Did you like this commercial?’ says Vinod Venkatraman, associate professor of marketing at Temple.

He, along with colleague Angelika Dimoka, brought in 300 participants to test a range of different methods commonly used to predict a commercial’s success. Using 37 recent ads, they monitored the viewer’s biometics, including heart rate and skin conductance, along with traditional focus group-style Q&A metrics. They also used more advanced techniques, including eye tracking and EEG scans, which monitor electrical activity in the brain. Finally, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) tests looked at blood flow in the brain.

They were then able to compare the results with two years of actual sales data supplied by the companies whose products were featured in the spots. The results pointed to a clear winner.

“We found that a brain area that we were able to capture using fMRI was the most predictive of advertising success,” says Dimoka. “So that brain area could double the prediction that was given to us by the traditional self-reported (focus group) measures of how well this commercial performed.”

Paying attention to changes in the ventral striatum

The fMRI scans showed that one specific region of the brain would come alive whenever a good ad came on the screen: the ventral striatum.

“It is well known because of its role in reward processing. It is like one of the main reward centers in the brain,” explains Venkatraman.

Located in the subcortical region, the ventral striatum is part of the circuitry that reacts to lots of different positive stimuli, like a bell that rings whenever something good happens.

“Things ranging from looking at attractive faces to eating chocolates to getting monetary rewards, all of them consistently activate this region,” says Venkatraman.

The concept here is that a good ad fires up this brain process, too, creating a feeling of desire in the viewer.

According to Dimoka, when this part of the brain is activated, ‘something pushes you to feel that you will get rewarded by using the product.’ And that is how you sell things.

Just don’t call it the brain’s ‘buy button’

Venkatraman says the findings are getting a lot of hype in the press, with some questioning whether or not fine-tuned ads would be a net positive.

Do we really want sugary cereal ads to more accurately hone in on impressionable kids, or politicians swaying the vote with spots that exploit ventral striatum activity?

Is it really such a good thing to let marketers in on the ‘buy button’ in our brains?

“I hate the ‘buy button.’ There is no such thing as the ‘buy button,’ my god,” assures Carolyn Yoon, a noted neuromarketing researcher at the University of Michigan.

While there appears to be a connection between the ventral striatum and a feeling of desire, she says the brain is far too complex to be whittled down to a series of buttons and levers. There’s a lot more that goes into getting someone to make a purchase than just tickling this one subconscious sensor.

But Yoon says the industry is paying attention.

“I think eventually this will become a part of the portfolio of different methods that marketers use,” along with traditional focus groups, eye trackers and EEG.

On the ‘buy button’ point, the report authors agree with Yoon.

“There is not one buy button, and there will never be one,” says Dimoka. “What we are trying to understand is how people make decisions, and that is why we do these studies.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.