Colleges struggle to meet demand for mental health services

Listen

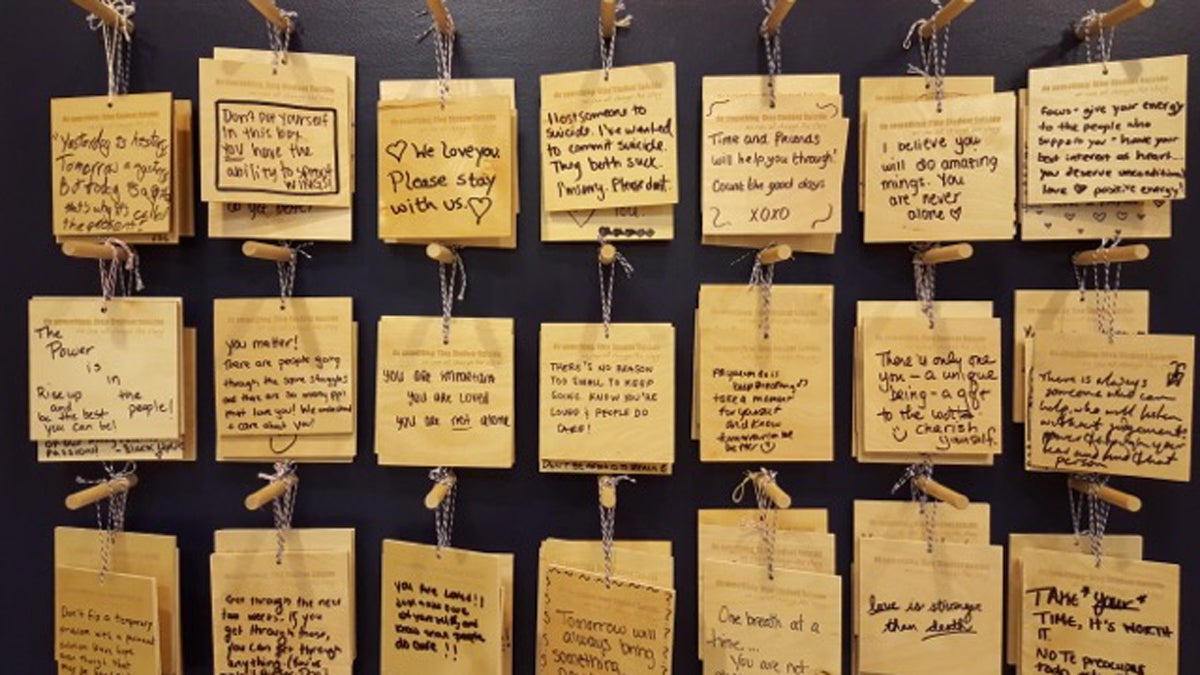

The wall of messages outside of University of Michigan's Counseling and Psychological Center. (Renee Gross/for WHYY)

More college students than ever before are seeking mental health services, but many centers are struggling to keep up with the growing demand for help.

Over the past 15 years, college counseling centers have been doing more outreach. They’ve introduced special initiatives, such as the National Depression Screening Day, to encourage students to pay attention to their mental health. Now—due partly to the success of their outreach—more college students than ever before are seeking mental health services. But many centers are struggling to keep up with the growing demand for help.

Dr. Todd Sevig is the Director of the University of Michigan Counseling and Psychological Center (known as CAPS). He says that the role of the center goes beyond counseling.

“Our job is to really help individual students, but we all also try to help the culture, the community, the campus,” he says.

Creating a culture more accepting of mental health issues has had some unexpected consequences. It means that more students are feeling comfortable asking for help.

Dr. Sevig notes that “this is a wonderful thing”. But the increase has also presented some challenges.

“Just this fall semester, we had an increase of 20 percent in terms of students coming in requesting services,” says Dr. Sevig. “There was one week compared to the same week the year before that the increase was 45 percent.”

The increase has been hard on the center. Dr. Christine Asidao is the director of engagement and community outreach at the University of Michigan CAPS. She says, “We have a large staff – around 53 people. But if you think about our student population- it’s not always enough for 43,000 students, right?”

The entire staff had to think creatively to try to address the students’ needs. So they hired temporary staff, increased the number of groups available, and did more workshops on preventive coping skills.

“We tried many different things,” says Dr. Asidao. “But again the numbers were kind of staggering.”

University of Michigan isn’t alone. Colleges across the country are experiencing a similar boom in demand for mental health services. Again, this is a good thing.

Dr. Victor Schwartz is a psychiatric professor at NYU and the medical director of the Jed Foundation which helps promote mental health on college campuses. He says, “in some ways, we’ve made some headway in that more students are prepared to reach out for help sooner because I think that, as a system, we’ve been doing a good job educating young people.”

But education and outreach isn’t the only reason behind the swell of traffic at counseling centers.

“There are some number of young people who, in the past, might have not been able to make it to college and other higher-ed settings, who now are able to attend, but they come with their medical and mental health histories,” says Schwartz.

Another change is that students are seeking help at their college counseling centers instead of in their communities. Why? Money. In the community, the cost of treatment depends on what your insurance covers. But on campus, mental health services are included in cost of tuition.

Now college counseling centers are trying to expand to offer more services to more people. But first, they have to go through the backlog of students already signed up for help.

Schwartz says, “If you follow college newspapers, you’ll certainty regularly see articles that are decrying a two or three week wait to be seen at the counseling service.”

Taylor, a sophomore at UM, acknowledges that sometimes it can take a while to get an appointment. She decided to visit the CAPS Counseling Center her freshman year. At the time, she was experiencing depression and self-mutilation. She says that when you’re struggling with feelings such as self-hatred and frustration that “a week is a long time to wait.”

Back at University of Michigan’s CAPS Counseling Center, Dr. Sevig says he is working on this issue. He notes that the center now has a crisis counselor on duty for students who need to be seen immediately. He’s also in the process of addressing the other concerns brought about by the increase of student demand. But he doesn’t want the outreach to stop. In fact, he wants to build on it. He wants to reach groups where mental health stigma still hasn’t gone down.

“More students are engaged in mental health this year and the last two years than ever before,” says Dr. Sevig. “And so we are both promoting, helping, supporting that, but also trying to extend that. How can we use that wave for the greater good, here?

Dr. Sevig is working with his staff to put his money where his vision is. This spring, large signs advertising the college counseling center will appear inside the University’s buses. Despite strained resources, he says he hopes this campaign will be taking one more step towards creating a healthier campus culture for all.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.