Syrian American doctors go to help heal those suffering in civil war

Listen-

-

-

-

-

-

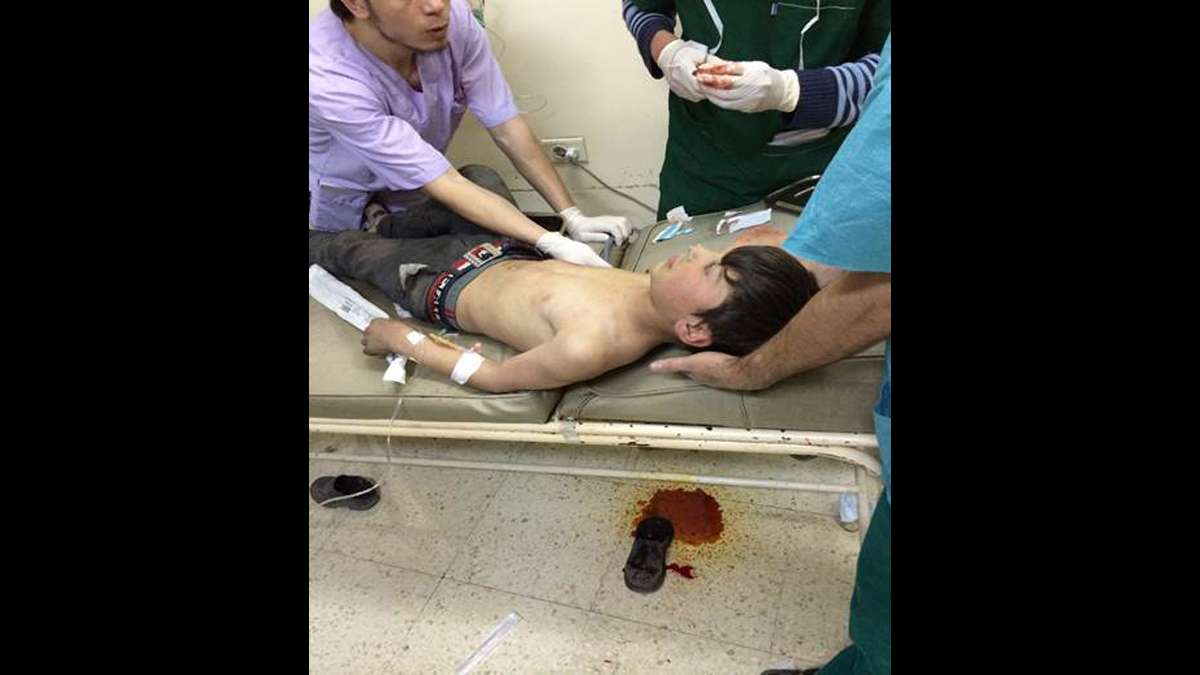

Dr. Abdalmajid Katranji

-

In conditions beyond primitive, where a bit of sanitized garden hose is used for surgical tubing and blacksmiths fashion metal scraps to hold broken bodies together, a group of Syrian American physicians hope to help the wounded and sick by any means necessary.

Since war broke out in Syria in March 2011, it’s claimed an estimated 170,000 lives as it’s driven countless others from their homes. Another casualty of war has been the delivery of basic and emergency health care.

Dr. Rim Albezem, who has a thriving cardiology practice in Bucks County, is acutely aware of the civil war and the toll it’s taking on civilians and the country’s health care system.

She and other Pennsylvania-based Syrian American doctors interested in heading an artificial-limb program recently visited a clinic at the border of Turkey and Syria on a fact-finding mission

What she saw there, she said, “is beyond any human core capacity to absorb and ignore.”

“I saw mostly patients with brain injury or spinal cord injury lying in bed with no appropriate mattress, with open sores,” Albezem said. “Severely depressed, no eye contact even with the treating physician … they had no hope and no interest in treating themselves.”

Most of the patients she saw were young men in their 20s with injuries, she said, “inflicted by either the regime or ISIS, the terrorist organization.”

From social gatherings to lifesaving mission

Albezem is an active member of SAMS, the Syrian American Medical Society headquartered in Chicago. Originally a place for social and professional gatherings, its mission changed as soon as the war in Syria began. As it became an active medical relief organization, it has raised about $15 million to do its work.

The organization’s National director Dr. Zaher Sahloul, met recently with Pennsylvania and New Jersey physicians at Albezem’s home in Newtown.

Just returned from a risky trip where he performed surgeries in a half-destroyed hospital near Aleppo, Sahloul documented his journey with narratives and photos. In one of them, the window of the operating room in the only hospital area that remained intact was blocked by stacked sand bags.

“I am a critical care specialist, so when I go and do medical missions, inside Syria, I’m dealing mostly with patients who’ve had injuries related to bombing and shelling, sniper wounds, gunshot wounds, crush injuries related to destroyed buildings,” Sahloul said.

“It’s estimated that there’s about 500,000 Syrians who have lifelong disabilities related to the trauma and the injury and the amputations,” he said. “We’re also dealing with psychosocial or psychiatric trauma related to the destruction, to the killing and the torture.”

As the most prominent member of the organization, Sahloul in May presented a revealing report to the House Foreign Relations Committee to elicit support and bring visibility to the war. He quoted findings from the World Health Organization to illustrate the enormous medical toll the war is taking.

“The WHO estimated that 50 percent of Syria’s hospitals were destroyed, and 15,000 Syrian physicians have fled or have been forced to flee Syria,” he said.

Out of Damascus University, on to very different paths

Sahloul and Albezem both studied medicine at the University of Damascus. One of Sahloul’s classmates was Bashar Al-Assad, then studying ophthalmology and now president of Syria. Complicated family and political reasons led Al-Assad to turn his back on healing, and follow in his father’s footsteps as a brutal dictator, Albezem said.

At the Bucks County meeting, Sahloul was accompanied by his colleague Dr. Abdalmajid Katranji. Born in the U.S. of Syrian parents, Katranji runs a hand clinic in Michigan.

He has become a sort of trouble shooter in the Syrian medical relief effort by combining high- and low-tech techniques to help Syrian doctors operating in the war zones. Those approaches include using YouTube and Skype for “virtual surgeries” to adapting any available object.

“If I need materials such as screws or plates, if you know there’s a local mechanic who is a bit of a blacksmith, you try to engage them and see what they can do to create some of the devices or the instruments that you would otherwise use,” Katranji said.

He also enlists local seamstresses for improvised suture threads and needles or disinfected gardening hoses for surgical tubing.

To cross the border between Turkey and Syria, SAMS doctors rely on an underground network of people who escort them to improvised clinics or warn them when it’s not safe. A number of field hospitals have opened on in the Turkish side of the border.

Since it began, SAMS said its doctors have treated half a million patients, performed 70,000 surgeries and trained about 500 local medics.

Fulfilling an oath, acting on faith

Risks, Returning to the safety of his practice in the United States is always emotional, said Katranji, especially after a recent near-miss explosion.

“You hug your wife a little bit harder, you kiss your kids a couple more times, because you just realize how close you were,” he said.

His family understands the risks he must take, Katranji said.

As a Muslim, doctor and American, like many of his colleagues at SAMS, he said he’s bound by faith and by medical oath to protect and care for all the wounded, no matter what side they’re on.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.