Scranton vet has no regrets over letting Army test mustard gas on him

Listen

Walter 'Babe' Gantz at his home in Scranton, Pa. (Todd Bookman/WHYY)

There’s a working class neighborhood in South Scranton, Pennsylvania with hills steep like San Francisco’s. At the top of one block, Walter “Babe” Gantz holds court at his kitchen table, where he’s spread out documents and photographs from his time in the Army.

Born November 1, 1924, the straight backed 90-year old has spent most of his life here, in a neighborhood that used to be known as the “Polish Alps.”

He was in high school here when the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor. He graduated, enlisted, and began training as a combat medic, though he claims infantry would have been a better fit.

But before heading to Europe with the rest of the 95th Medical Battalion, Gantz was approached by his commanding officers.

“They asked for volunteers,” said Gantz. “Of course, when you are 18, you are young and foolish, so you volunteer.”

Gantz (left) poses outside a medical tent in Holland in 1944 or 1945 with Dick Kent.

Gantz (left) poses outside a medical tent in Holland in 1944 or 1945 with Dick Kent.

He was sent on a five-week secret mission to Bushnell, Florida. The “Bushnell Project” was part of a massive series of covert chemical weapons tests, kept classified by the military until the early 1990s. An estimated 60,000 American soldiers were subjected to agents including mustard gas; masks, protective clothing and various ointments were evaluated.

Gantz’s own father had been injured by chemical weapons in World War I, and there was widespread fear this type of warfare would return to the battlefield. Part of his medical training involved treating chemical burns, so Walter knew full-well what he was getting himself into. Still, the mission proved to have moments you couldn’t prepare for he said.

“There was a Canadian Halifax bomber,” he said. “That bomber used to come overhead, two, three-hundred feet above ground, and they would actually spray us with chemical agents.

“You know, it is a funny thing. I heard that Halifax Bomber for years and years. That just stayed with me, really,” he said.

Gantz would make it through that first month of tests physically unharmed.

“We would march several miles wearing the gas masks. We would run a quarter-mile, maybe half a mile, with the mask on. And we chopped down trees, dig trenches…the field tests, that was brutal. That was tough.”

Then one evening, in March of 1944, he and his fellow soldiers were sleeping in a field, two to a tent, when they were caught off-guard. A fog of mustard gas rolled through the area.

“During the nighttime, they would set off these chemical bombs,” he said, “and they explode these bombs, and the end result, we were, the both of us, were burnt.”

Dime-size blisters bubbled up on his lower legs and back, while his eyes and lungs began stinging. His tent-mate, Verle Perrin, who would become a lifelong friend, was more seriously hurt.

Medals awarded to Gantz for his World War II service include one (center) given for his participation in the Bushnell Project (Todd Bookman/WHYY).

Medals awarded to Gantz for his World War II service include one (center) given for his participation in the Bushnell Project (Todd Bookman/WHYY).

An ambulance brought them under heavy guard to MacDill Air Force Base, near Tampa, where he was instructed not to call home, and wasn’t allowed visitors. Still, he says his ten days in the hospital weren’t all bad.

“They treated us royally. You know, funny thing how you remember things even after 70 years. But, in them days, burlesque was very popular, OK. And there was a fan dancer — the most popular fan dancer in the country — by the name of Sally Rand.

“And she came and put on a show for us…I don’t remember too much about the hospital, but I remember Sally coming,” he said with a laugh.

The “Babe’s” wife of 65 years, Jean, sits across the table from us. She throws me a half-smile in response to the Sally Rand story.

An oath, and a broken promise

He didn’t used to talk about these mustard gas tests — with her or anyone — for decades following the war.

“You have to remember, none of this is on my discharge,” said Gantz. “We were threatened, if we were to say anything to anyone, family included, that we would wind up in Fort Leavenworth — that’s a prison. Of course, when you are young, you are very fearful, and so I kept mum all that time.”

Gantz didn’t suffer any long-term health effects from exposure to mustard gas, though several of his buddies including Verle Perrin did. It would take until the early 1990s, when under scrutiny, the Veterans Administration finally promised compensation for the severely injured. (Recent reporting by NPR finds those promises went largely unfulfilled.)

“You know, the sad thing about it, the government actually turned their backs on us. They never followed up on us, to how we were doing or anything like that.”

Gantz says he could have left that hospital in March of ’44 and gone back to civilian life. Instead, he decided to put his medical training to good use, in places like Holland, France, Belgium and Germany.

“In them days, patriotism was a very big thing, you know what I mean? And so I decided to go back with the 95th, and I’m glad I did. I really am,” he said.

Inside his hilltop house, a collection of medals, including the Bronze Star, hang on the wall behind glass.

Gantz says members of the 95th Battalion held reunions over the years, but nobody ever mentioned the “Bushnell Project” or similar chemical weapons tests. They swore an oath to their country. An oath none of them took lightly.

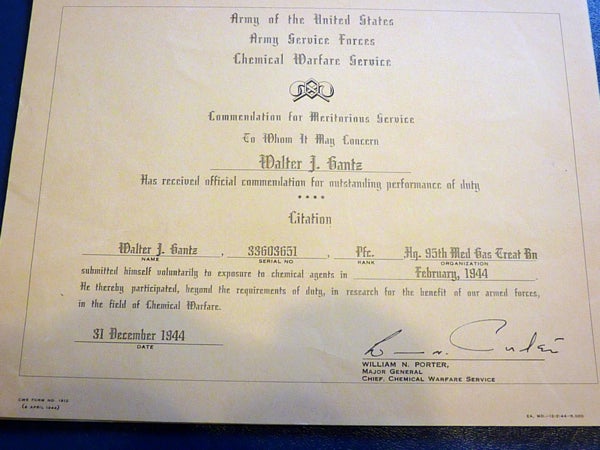

A certificate commends Gantz for his participation in the Bushnell Project. (Todd Bookman/WHYY)

A certificate commends Gantz for his participation in the Bushnell Project. (Todd Bookman/WHYY)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.