Pa. college chemistry students find carbon monoxide in common vaping devices

The research challenges electronic cigarette industry claims about health risks the devices pose.

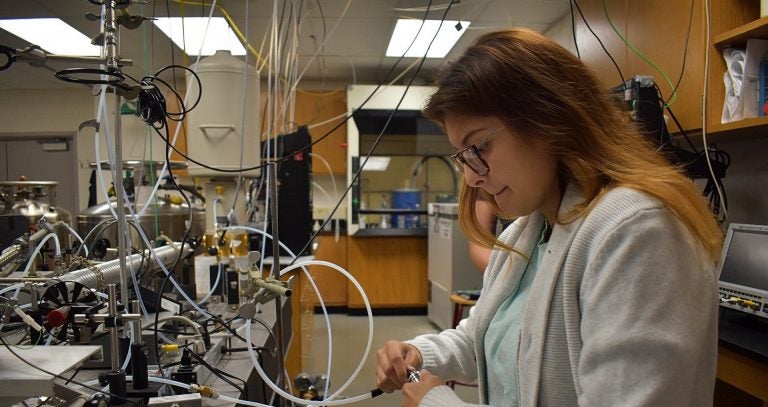

Buckenell chemistry senior Anna Islas connects a vaping device to a hose for testing. (Brett Sholtis/Transforming Health)

Electronic cigarettes release potentially harmful levels of carbon monoxide, according to research conducted at Bucknell University in Lewisburg that challenges vaping industry claims.

The study shows that two common vaping devices were emitting toxic gas, which is also found in cigarette smoke, during tests that simulated how a person would use them. Carbon monoxide levels “rose exponentially” when vaping devices were turned to higher power settings.

When the e-cigarettes were turned up to their maximum setting, those levels were 20 times higher than outdoor air quality standards, the study shows.

The Bucknell researchers said vulnerable populations should avoid vaping or limit use to lower power settings. They said e-cigarette makers should consider limiting the power range on the devices.

The study, begun in 2016, is being published at a time of heightened scrutiny over the risks of vaping. Federal health agencies are searching for what’s causing a vaping-related illness that has killed at least 33 people and put more than 1,400 in the hospital.

The research, slated for publication this month in the British medical journal Tobacco Control, is the second study this year to find carbon monoxide in e-cigarettes. A study published in January in Chemical Research in Toxicology noted the gas was present in “sub-ohm” vaping devices, a term for e-cigarettes that have been modified to increase their power output.

The Bucknell study was spurred by the curiosity of undergraduate chemistry students, said Dabrina Dutcher, an assistant professor of chemistry and chemical engineering at Bucknell. Students realized that atmospheric chemistry equipment could be used to test vaping devices.

One of Dutcher’s colleagues, chemistry professor Karen Castle, already had established a system for measuring carbon monoxide concentrations using a laser.

The two scientists used Castle’s method and a pump system that would simulate the action of someone inhaling the vapor.

“E-cig makers would have you believe they’re just gently aerosolizing it, but that’s not true,” Dutcher said. “There’s actual chemical reactions happening.”

Some of the levels they found were shocking, said Jewel Cook, a senior chemical engineering major who worked on the project.

“They were such high quantities that we didn’t really believe it was carbon monoxide at first,” Cook said.

Researcher Anna Islas said she spent the past two-and-a-half years adjusting settings to make sure she wasn’t doing things like burning the cotton wick used to soak up the e-liquid that contains the flavors and the addictive nicotine.

“So then once we started to see data without burning the cotton, and we frequently changed everything inside the atomizer tank, we realized it is carbon monoxide coming straight from the e-liquid,” said Islas, a senior in the chemistry department.

While this study was limited to two types of devices, called “box mods,” purchased at local shops, Dutcher said she expects the same principles to be at work in all e-cigarettes.

That raises questions about what’s in the flavorings that go into e-liquid, she said.

Those flavors are considered proprietary, meaning companies don’t have to list their ingredients. Because carbon monoxide levels varied from one flavor to another, it’s likely that something in some of those flavorings is adding to the chemical reactions, Dutcher said.

Health officials haven’t targeted carbon monoxide as they study the mysterious lung illness that has killed at least one person in Pennsylvania and hospitalized dozens. However, Dutcher said its presence indicates that other harmful substances are being released through related chemical reactions.

She pointed to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recent guidance that people should avoid vaping, saying that experts believe more than one factor is contributing to the illnesses.

“I wish we knew what to tell people to avoid, but we don’t know that yet,” she said.

Carbon monoxide in vaping devices isn’t necessarily a cause for concern, said David Peyton, a chemistry professor at Portland State University in Oregon. He noted that cigarette smokers have elevated carbon monoxide levels, and he said he wasn’t alarmed by the levels of the gas described in a preliminary report of the study.

However, the Bucknell team’s finding points to a need for more research, Peyton said. Ideally, that would involve clinical studies of people using the devices.

Alex Clark, CEO of the Consumer Advocates for Smoke Free Alternatives Association, said the researchers should have compared carbon monoxide levels produced by vaping devices to what is created by smoking traditional cigarettes.

Clark said the vaping industry largely views e-cigarettes as a way for people to enjoy nicotine while reducing their intake of carcinogens and harmful chemicals.

“We live in a world where people take risks, and people enjoy taking substances that change their mood,” he said.

Bucknell’s Islas and Cook said some college students start vaping without ever having smoked a cigarette, and many are unaware of all the potential risks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.