What Trenton’s ‘Central Park’ once looked like

There are many ways to get to Trenton’s Cadwalader Park, whether cycling alongthe D&R Canal State Park or following the winding path to Ellarslie, the Trenton City Museum.

This summer, Ellarslie has launched an ambitious exhibition, Cadwalader Park: An Olmsted Vision, on view through September 17, with an opening reception Saturday, July 15, 6-9 p.m.

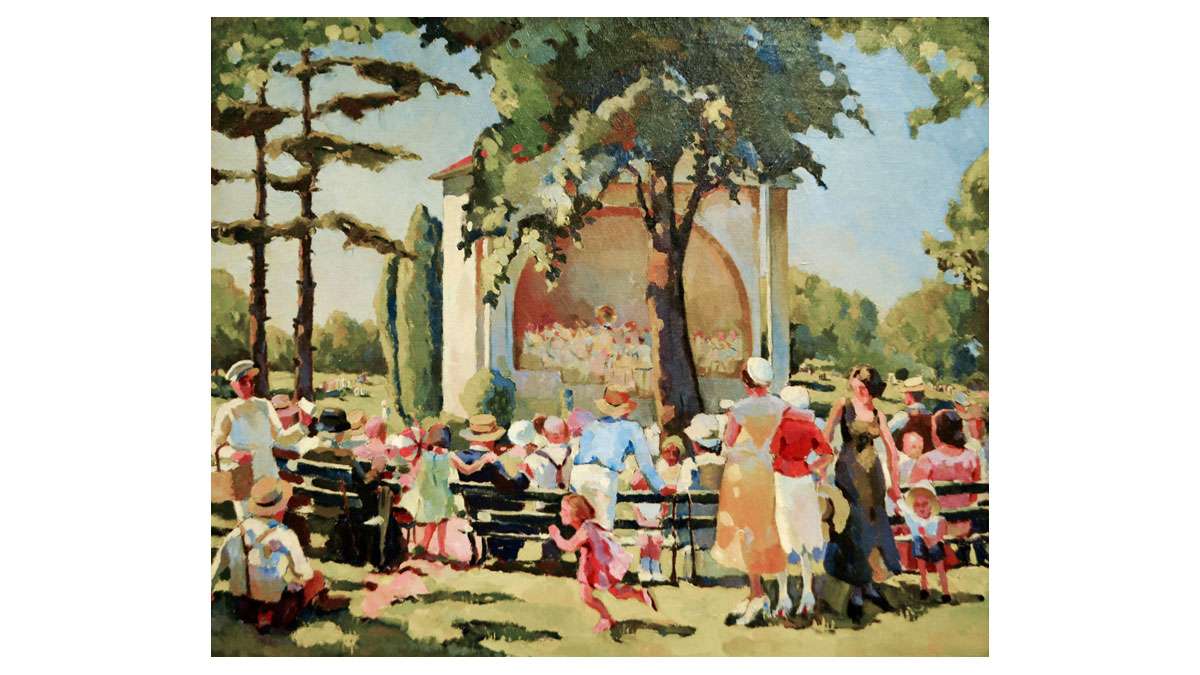

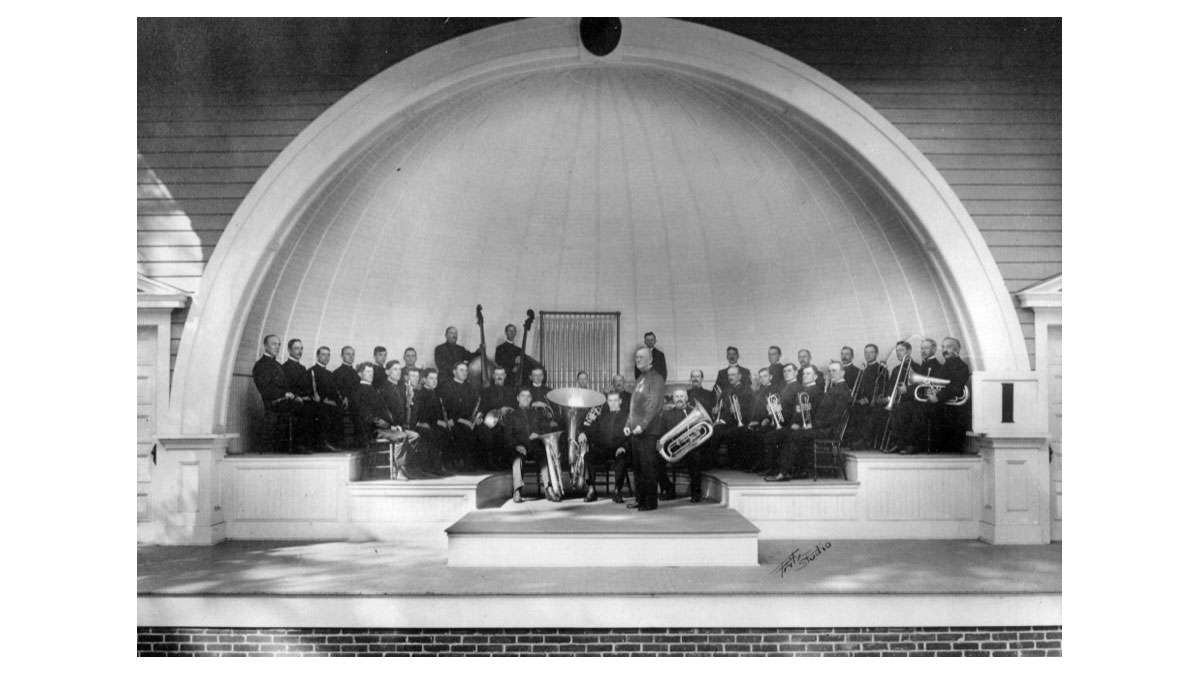

At 109.5 acres, Cadwalader Park is the largest park in the City of Trenton, beloved by those who recall pony rides, picnics, concerts and the balloon man, the monkey house and animal paddock, inhabited by deer, geese, ducks and even unusual animals such as peacocks and camels. The park serves as a reminder that Trenton, in its heyday, was a center of innovation, entrepreneurship and skilled employment.

An Olmsted Vision is timely, as a $2.4 million project is underway to restore and upgrade Cadwalader Park, with funding from the Department of Environmental Protection ($2.3 million) and the City of Trenton ($120,000). Plans include improved pathways and trails, with handicapped access; recreation and playground area and equipment upgrades; picnic grove relocation and upgrade; and more modern amenities.

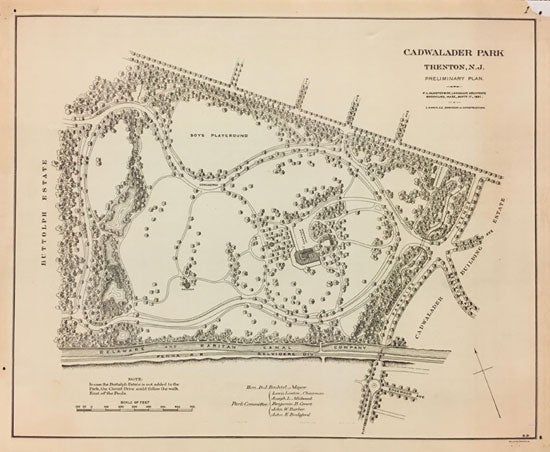

Cadwalder Park Plan by Frederic Law Olmsted, architect of New York City’s Central Park (Photo Trenton City Museum)

“This is the only park in the state designed by (Frederic Law) Olmsted,” says Cadwalader Park Alliance’s Randy Baum. “Though the park has suffered through several decades of funding cutbacks, it still retains many of the landscape and spatial qualities present in the original plan.”

Frederick Law Olmsted, widely known as the designer of New York City’s Central Park, is considered the father of American landscape architecture. Born in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1822, Olmsted, who never completed college, studied surveying, engineering, chemistry and farming, and dabbled in such careers as scientific farmer, merchant seaman, newspaper correspondent and author. He toured the parks and private estates of Europe, publishing books on his travels. Through his writing, he opposed slavery and argued for abolition.

By the time he began his work in landscape architecture, he believed that the public realm should be a respite; a place to retreat from the stress of urban life; and that public open space should be accessible to all.

In 1857 he became superintendent of New York City’s Central Park and, along with architect Calvert Vaux, won the design competition for the park the following year. He spent the next seven years as the primary administrator in charge of the construction of Central Park. Olmsted’s success in park making led to his renowned career designing and creating some of the nation’s most important urban parks, from Boston and Buffalo to Milwaukee and San Francisco.

By the time Olmsted began designing Cadwalader Park in 1890, he had been planning parks in America’s leading cities for more than 30 years. Cadwalader Park is considered Olmsted’s last great urban park.

As with plans for Prospect and Central Parks, Olmsted’s plans for Cadwalader relied on the creation of long views across open, rolling meadows that contrasted with more densely planted park edges. Over the years, tree plantings in Cadwalader have closed many of the long vistas and open meadow effects envisioned by the Olmsted design. Clusters of trees have blocked natural high points, such as the Overlook, that might otherwise provide a prospect for views.

The canopy in Cadwalader Park includes maples, oaks, tulip poplars, American beech and more recent plantings of spruce. A decline of native trees was paralleled by an increase in Norway spruces and London plane trees—the Norway spruce is neither a shade tree nor one originally recommended by Olmsted.

Over the years, the Ellarslie mansion has been a restaurant, an aviary, a speakeasy and an ice cream parlor. The lower floors were converted into a monkey house in a Works Project Administration project in 1936. The construction of the large pond in the northwest corner of the park was also a WPA project.

The park remained popular with city residents after World War II but by the 1970s lack of maintenance had caused the condition of the park to deteriorate. In 1971, the City began a project to convert Ellarslie from a monkey house to the Trenton City Museum. Ellarslie and Cadwalader Park were placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, and the Museum opened in 1978.

Board member Karl Flesch grew up on a farm in Yardville, where he got his fill of animals, but came to Cadwalader Park for the rides. He remembers the strong smell of the monkey house in the early 1960s. “The monkeys were kept in cages that extended from the indoors to the veranda, where they could be viewed. I wish that more people would come and make use of park today. It needs restoration for future generations to enjoy it.”

Viewers can see history exhibits in Ellarslie’s second floor galleries, depicting the life and works of Olmsted and the history of the park including vintage and contemporary photos, park memorabilia, concepts from the 2000 plan for the restoration of Cadwalader Park and much more. The first floor galleries display works of art specific to the park, contributed by contemporary artists and on loan from private collections.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.