SE Pennsylvania is driving less even as economy grows, bucking regional and national trends

A few weeks ago, I received a seemingly random email with the subject: “Interested in Test Driving a New GM Vehicle?”

Assuming it was spam and not interested in buying a car anytime soon (or ever, really), I deleted it and didn’t give it second thought until a few days later, when my girlfriend asked if I wanted to go on a trip to Longwood Gardens. She had this free car for a week, you see, a Chevy Volt, because someone at Chevrolet emailed her, asking if she wanted to test drive an electric car for a week, no strings attached, even though she also had absolutely zero intentions of buying a car anytime.

Car salesmen have used pressure tactics and test-drives to get potential buyers to commit ever since the Model-T. But why were these massive auto manufacturers targeting the founder of sustainability app start up and an outspoken bicycle booster?

Well, we’re both millennials with a considerable amount of social clout (or, in this case, Klout) and the auto industry is giving influencer marketing a try. In a world where ads show up everywhere from urinals to faces, marketers are trying to cut through our wary filters by getting your friends and family to hawk their wares for them. This sort of “organic” advertising has been shown to be highly effective.

Why aren’t non-car companies bombarding my email with free offers? (Seriously, let’s go guys.) Millennials aren’t buying cars as much as our older Gen-X siblings did. And the nation’s most populous generation is starting to enter its thirties, traditionally a prime car buying time. So carmakers, desperate to convince my generation to pick up the keys, are resorting to tactics like offering free test-drives to thirty-somethings like me, in addition to their regular strategy of bombarding us with commercials and product placements.

Millennials aren’t buying as many cars because they don’t need them: millennial driving is down across the nation. But it’s not just millennials. Driving – usually measured by daily vehicle miles traveled (DVMT) or annual vehicle miles traveled (AVMT) – has been down over the past few years, regardless of age.

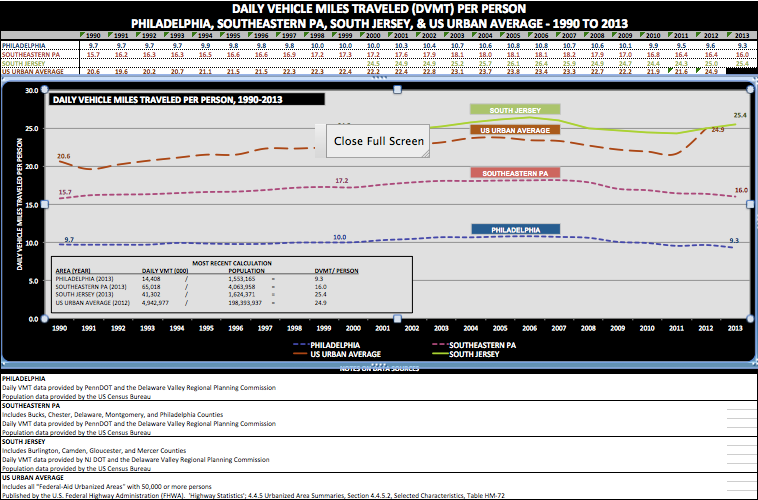

That downward trend in DVMT may be coming to an end, though. In 2014, DVMT in the United States rose for the first time since the recession, as the economy continued to improve, more people returned to work, and gas prices plunged. In urbanized areas across the U.S., DVMT per capita started to rise in 2012, shooting up to 24.9 miles per day from 21.6 in 2011.

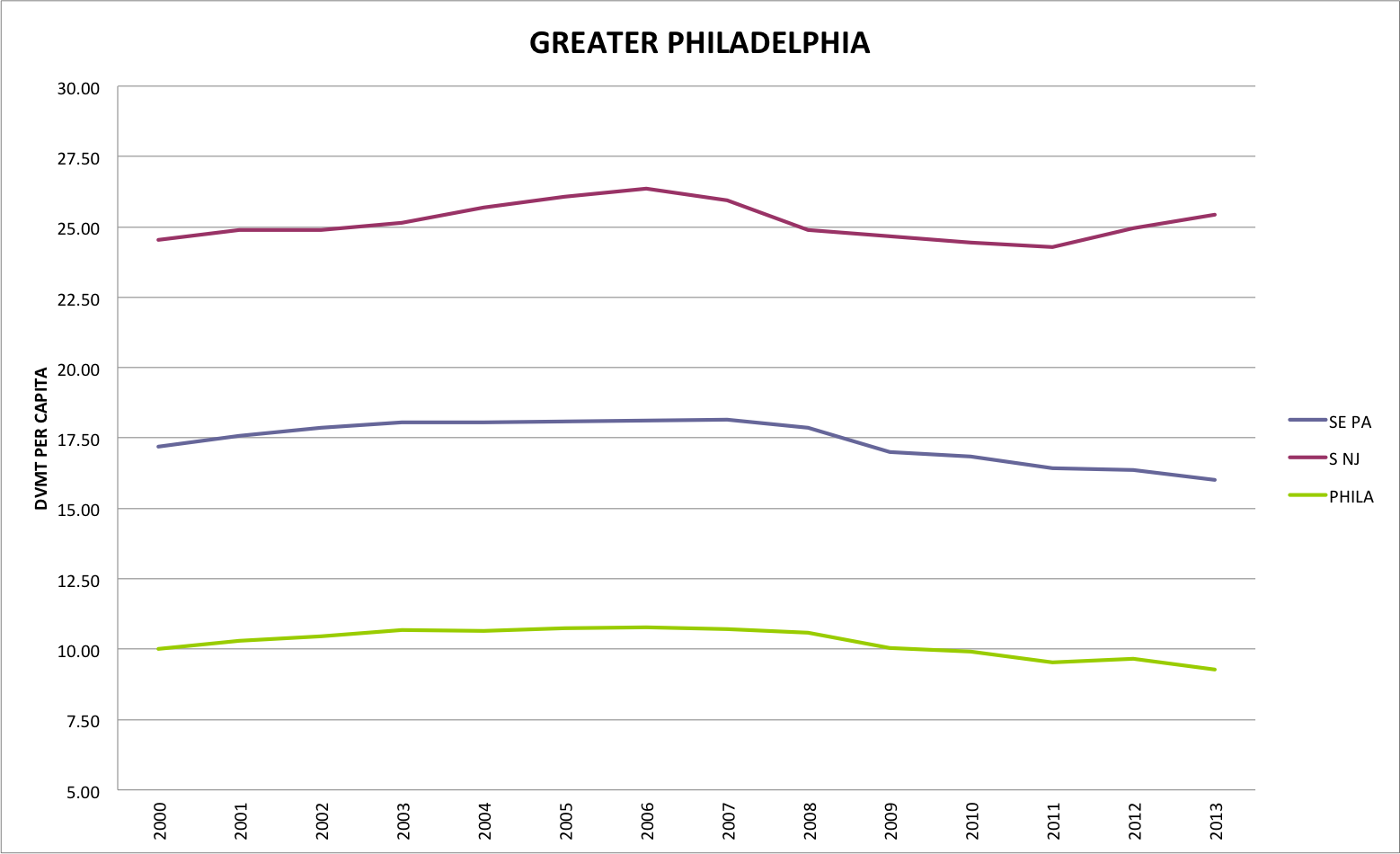

Unlike the rest of the nation, Southeastern Pennsylvania isn’t rushing back to rush hour traffic. According to a recent analysis by Erik Johanson, Manager of Strategic Planning at SEPTA, DVMT per person in Philly and its Pennsylvania suburbs continued to decline, even as the recession came to an end in the region. But, perhaps driven to the highways by the ubiquitous sounds of Springsteen hits like “Racing in the Street” and “Thunder Road”, South Jerseyans have increasingly driven more since 2011.

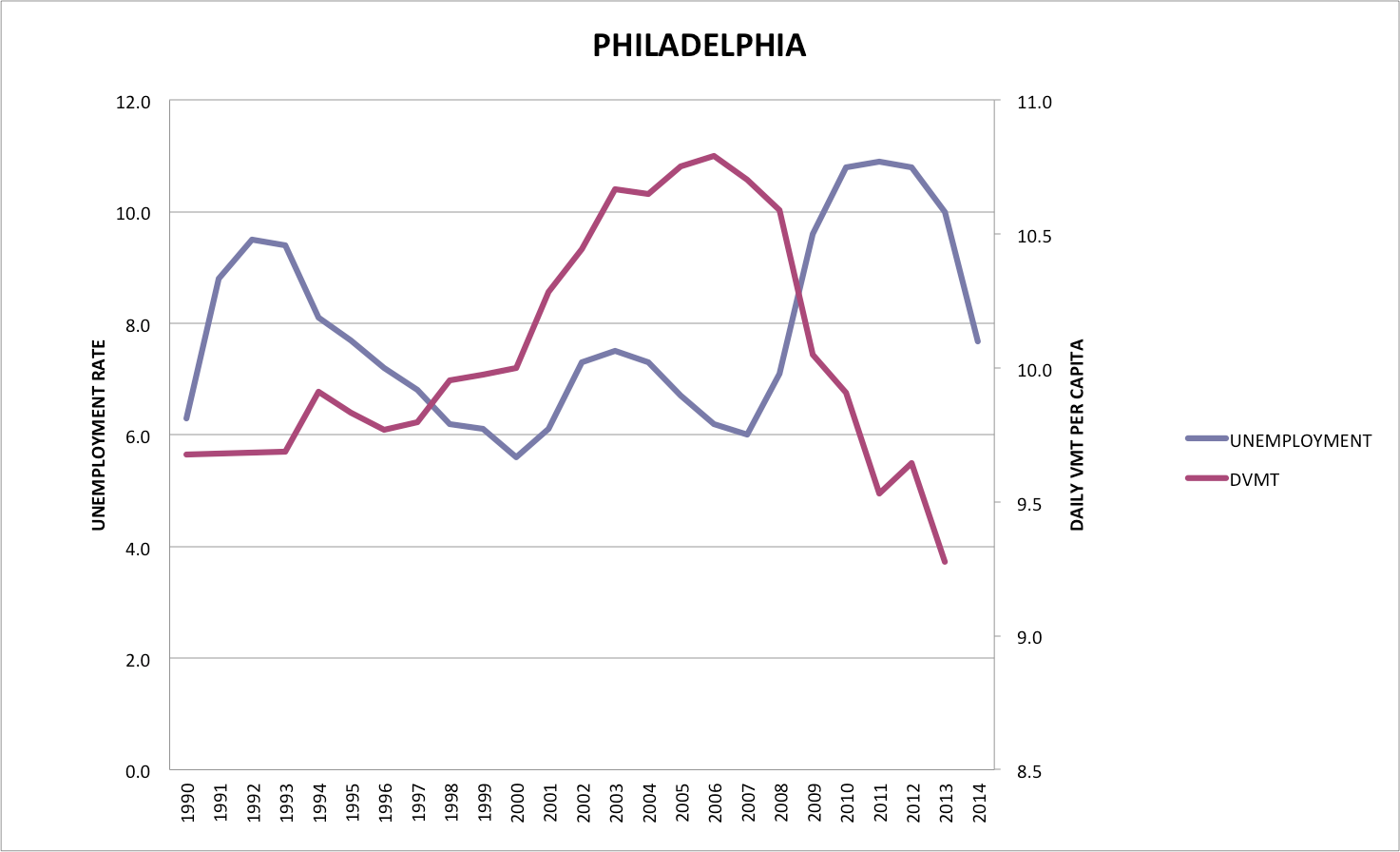

In Philadelphia, unemployment has come down from a recession high of 10.9 percent in 2011 to 7.7 in 2014. But at the same time, Philadelphia’s DVMT has been falling since 2009. And it’s also been falling in the suburban counties SEPTA serves, leading Johanson to credit “dense walkability in the city and a comprehensive regional transit system connecting people to jobs,” for a lot of the decline.

South Jersey shares the same economy as Southeastern Pennsylvania but towns like Cherry Hill and Collingswood were designed around cars, not transit. If you live in Medford, driving is the only way you can get around, and lower DVMT is a clear indicator that times are tough and many people are staying home just to save on gas. But in Philly and many of its suburbs, neighborhoods grew around trolley stops and train stations. Towns like Ardmore, Wayne and Lansdowne grew tightly around their railroad stations, creating walkable communities.

“People really do have options in Philadelphia that they might not have some other places,” said Christopher Puchalsky, Deputy Director of Transportation Planning at the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission.

“When you give people transportation options – real options, not you can drive or… you can put you life in danger [while waiting for a bus] in a grassy median with no bus stop – they tend to take them.”

While Philly has options – and will add another when Indego bike share launches in a few weeks – it also has one of the highest poverty rates in the nation. When DVMT declines because of options, we can celebrate the reduced traffic and greenhouse gas emissions, but when it declines simply because households can’t afford to put gas in their car, that’s obviously bad.

Compared to South Jersey, where driving really is the only way to get around, it’s difficult to parse what exactly causes Philly’s low and declining DVMT. But given that it hasn’t spiked coming out of the recession suggests a deeper change in how Philadelphians get around.

Almost all of Philadelphia’s population growth can be attributed to the rise in the millennial population (immigrants are the other big factor). It’s no coincidence that as more millennials move to the city, fewer of them have bought cars. Just why isn’t clear, but is probably a combination of the facts that, compared to older generations, millennials hold more student debt, face worse job prospects, wait longer to get married and wait even longer to have kids. All these factors make millennials more likely to stay in the city, and less likely to drive. It’s a cycle – virtuous if you like cities, vicious if you make cars.

But it isn’t just the kids. Puchalsky noted that more people are biking to work in Philadelphia across all ages – it’s not just clichéd hipsters in skinny jeans. And while older generations still tend to move out of the city they aren’t moving out in the same numbers as they once did.

“Urban areas are not seen in the same light as they used to be,” said Puchalsky. “Crime rates are down dramatically. Tighter pollution controls make it nicer to walk around the city.” Puchalsky also noted that, while far from ideal, race relations have improved since the 60s and 70s.

Johanson’s analysis shows a relatively sharp jump in DVMT per capita across urbanized areas, suggesting that even as people move to other cities more, their driving patterns are still highly influenced by their economic circumstances. But most American cities don’t have public transportation systems as robust as SEPTA, which has the nation’s sixth largest ridership. Both Houston and LA have significantly larger populations than Philly, but SEPTA has more passengers than those two cities’ transit agencies combined.

Nationally, GDP and VMT are no longer as highly correlated as they once were suggesting that more people are moving to cities where they have real transportation choices. This change also reflects how our economy has become less driven by hysical goods, which need to be shipped and trucked from place to place, and more by services and intangible goods like computer software.

Johanson’s study doesn’t include DVMT for 2014, which is when gas prices started to drop significantly, meaning we might still see driving numbers pick up regionally. But SEPTA’s ridership is up so far in the current fiscal year that began last July, so even if it turns out that DVMT is going up in the area, that doesn’t necessarily mean people are abandoning the subway for a Subaru. It may be that people can simply afford to travel more, generally. Both Johnson and Puchalsky said they expect to see a small bump in the region’s DVMT in 2014, but not as large an increase as in other cities.

Johanson admits his analysis looks at macro data, “so you got to take everything in context and with a grain of salt.” DVMT is a top-line number, the effect from a dozen factors. Gas prices undoubtedly pushed some to public transportation when it was relatively high in 2006. And now that they’re historically low in 2014, some SEPTA passengers will trade in their fare cards for Ford cars.

But if Philadelphia only sees a small increase in driving despite the short-term influences, and alternative modes continue to grow, driven by new attitudes about public transportation and bicycling, then how we spend our precious few transportation infrastructure dollars will need to change, says Puchalsky. “I think there are real trends that really change the way we need to plan for our transportation system.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.