The hidden cost of child care in Delaware: Families skipping meals, quitting jobs and falling into debt

Some families are turning down promotions and making financial sacrifices to qualify for state help amid skyrocketing costs.

Listen 1:45

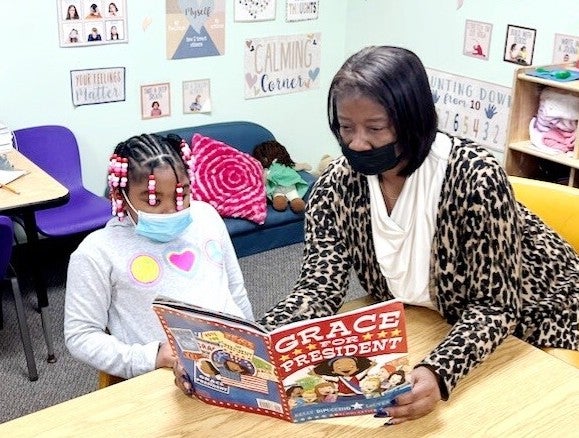

File: Melanie Price, who runs A Leap of Faith, reads with a student (Courtesy of Melanie Smith)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

In Delaware, the child care crisis has reached a tipping point.

Parents across the state face a daunting combination of soaring costs, limited availability and long waitlists, all while trying to maintain their jobs and provide for their families.

For many, child care has become one of their highest expenses, often rivaling or exceeding the cost of housing, transportation and food. With limited financial assistance and a lack of accessible programs, families are increasingly burdened, with many finding themselves in debt, cutting back on essential needs or even reducing working hours to avoid losing child care subsidies.

‘It’s not surprising, but disheartening’

Those challenges are reflected in a recent survey overseen by Kirsten Olson, CEO of Children and Families First, alongside other advocacy organizations and community groups. She said the findings highlight the undeniable strain on families.

“More than 75% struggle to afford child care that meets their needs. I don’t think that was surprising but I think it really demonstrates how child care and child care cost is a barrier for families,” Olson said. “What was disheartening to hear were stories like parents skipping meals to afford child care or turning down raises or promotions to maintain eligibility for state assistance that help them pay for child care. And that folks are even leaving the workforce altogether, because child care is such a critical issue for them.”

The survey, which captured the voices of over 400 families across Delaware, reveals a stark reality of a system stretched to its breaking point. Among respondents, 28% reported that an adult in their household had to leave the workforce or decline promotions due to a lack of child care, while 54% reduced their working hours.

Nearly a quarter of respondents reported living in debt due to the cost of child care, with some describing the financial burden as equivalent to a second mortgage.

“For families with young children, child care may be among their highest monthly expenses. So it may be more expensive than the mortgage payment or their rent. It may be more expensive than their car payment, their food, their utilities,” she said. That often leaves parents with difficult choices to make. “That’s when we hear about things like people reducing our work hours or quitting a job so that they can continue to find the child care that they need.”

Regional disparities and cultural barriers

The challenges in accessing affordable, quality child care are especially stark in rural Sussex County, where transportation issues and economic divides exacerbate the crisis.

“What I think about in Sussex County is transportation. Transportation is not as readily available as it is in New Castle County,” she noted. “Sussex County is a very large county and so if I’m working in Rehoboth, but I live in Seaford, those two places are far apart from each other. And trying to find child care that I need and the hours that are accessible and that I can get back and forth to can be a different challenge.”

“We see the different economic divides in the county — the eastern side of the county may have more financial resources, higher number of retirees. And then on the western side of the county, we tend to see higher needs and lower income,” she added.

Toni Dickerson, administrator of Sussex Preschools and chair of the Child Care Association of Sussex County, echoes Olson’s concerns, highlighting the shortage of child care services and resources in Sussex County, Delaware’s largest and most rural region.

“There’s not enough of us,” said Dickerson. “The biggest challenge is that there are not enough [spots] for child care. So at that point, affordability does not matter. There are thousands more children than there are [spots] and that is looking at all licensed programs, whether it is a center-based program like mine or family care programs where the provider is highly qualified.”

This shortage is evident in the Delaware Child Care Map Report 2024, which shows significant disparities in licensed child care facilities across the state:

- Sussex County: 168 facilities with a capacity of approximately 7,440 children

- Kent County: 167 facilities with a capacity of approximately 7,906 children

- New Castle County: 554 facilities with a capacity of approximately 38,663 children

Since the pandemic, Dickerson’s center has observed a striking shift: Where they once served a largely Latino population, they now see only a few families dropping off their children — a pattern that was unheard of before the pandemic.

“We have maybe three or four Latino families that are in our school age program,” she said.

“Pre-COVID, we had so many Spanish-speaking families. We are slowly seeing an increase in the Haitian Creole families, but again, not until the age of like 2 and a half, 3.”

For some communities, the barriers are even steeper. Households where Spanish or Haitian Creole is spoken were more likely to experience financial strain. These families often face additional hurdles, such as finding child care providers who are culturally and linguistically appropriate. While their struggles mirror those of English-speaking families in many ways, their lower-income status exacerbates the challenges.

Voices of families

With an option to add comments in the survey, a New Castle County parent earning less than $31,000 annually shared that accessibility and affordability were significant concerns — issues echoed by nearly 70% of Latino respondents.

“[Si el cuidado infantil fuera más fácil de encontrar o más asequible] económicamente podría ser autosuficiente. Mi salud mejoraría,tanto física como mentalmente,” ellos dijeron.

“[If child care were easier to find or more affordable] I could be financially self-sufficient. My health would improve, both physically and mentally,” they said.

Another parent from Kent County said if things were more affordable and accessible, they would be able to start their own business following that American dream.

“[Si gadri a te pi fasil pou jwenn oswa mwayen, mwen ta] fè yon ti biznis,” yo di.

“[If child care were easier to find or afford] I would start a small business,” they said.

As the next legislative session approaches next month, advocates like Olson and Dickerson plan to present their findings to legislative leaders, urging policy changes that include increasing state-funded preschool slots, expanding eligibility for child care subsidies and raising participation care rates to address the challenges families face.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.