Contemporary Lenape artists offer their perspective on Lenape history

“Never Broken” at Michener Museum in Doylestown, Pa., asked Indigenous artists to tell the history of the Lenape people.

Listen 1:27

Ahchipaptunhe of the Delaware Tribe of Indians and Cherokee, created large scale paintings inspired by the geometric designs on Lenape stamped baskets and pottery. His work is featured in ''Never Broken: Visualizing Lenape Histories,'' at the Michener Museum. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

David Haff, an artist who grew up in the greater Philadelphia region, is a member of the Cherokee and Delaware Tribe of Indians. He has adopted a Lenape word as a name: Ahchipaptunhe, meaning to talk strange.

Now based in Phoenix, Ahchipaptunhe identifies strongly with his Lenape heritage and incorporates it into his abstract works. But he had not personally encountered any historic Lenape objects. He presumed they didn’t exist.

“I grew up in the tri-state area, Lenapehoking, and I hardly would ever see any Lenape artifacts,” he said. “So when the Michener Museum said, ‘We have traditional Lenape artifacts and we want to show you,’ I was so ecstatic.”

“It sounds strange, but even looking at the pottery, I get shaky just being in the presence of these things,” he said. “I believed that they were lost.”

For the exhibition “Never Broken: Visualizing Lenape Histories,” now on view at the Michener Museum in Doylestown, Pa., Ahchipaptunhe created large-scale, monochrome abstract pieces based on the patterns of Lenape pottery fragments and woven baskets seen in the same gallery. Some of them date to the third century,

Borrowed from the New Jersey State Museum, the objects under glass have patterns that are echoed in Ahchipaptunhe’s paintings. The pottery was carved with hash marks; the baskets have a checkerboard weave stamped with graphics. The Lenape artisans likely used carved potatoes dipped in ink to stamp their baskets.

Ahchipaptunhe admits he has no idea what the patterns or graphics mean, if they represent anything literal at all. He is more interested in thinking about how his ancestors made things.

“Is there a story behind these forms? That’s something that I won’t ever be able to pull out,” he said. “But having this simpler conversation about form and design is important to me. As an abstract artist, I love that. It puts me in the driver’s seat to have a direct conversation with the viewer.”

“Never Broken” was curated in partnership with the Lenape Center in New York City, whose director, Joe Baker, says this is the first exhibition of contemporary Indigenous artists to feature Lenape artists, exclusively. Typically, exhibitions of Indigenous artists feature work of people from a variety of tribal backgrounds.

“This show is about a homecoming, a return, a remembrance of our ancestral land,” said Baker. “We have a responsibility to remember, to think about, and reflect upon this place that we come from and to create a response to that in our own way, in our own voice, in our own time.”

Baker included some of his own work in the exhibition, including a recreation of a Big House, a large structure that would serve as the basis of the Lenape system of religious beliefs. A building made of tall timbers acted as a gathering place to contemplate the natural and supernatural worlds.

In the center is a large pole in which a face has been carved, with 12 furrows in its brow.

“The Center Post, which was the connector for the lower world and the upper world,” said Baker. “If you look at the face, the 12 lines on the forehead represent the 12 levels of the upper world, the heavens.”

Baker also included several of his own large abstract paintings in the exhibition, including “Three Sisters,” in which he imagines his grandmother and her sisters returning to the Lenapehoking land.

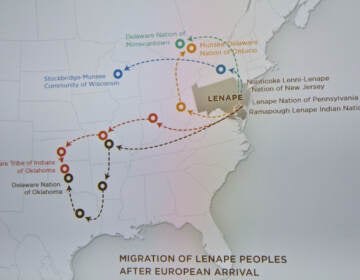

In the 18th century, the Lenape were forcibly displaced from the Lenapehoking, and continued to be displaced throughout much of the 19th century until they landed in Oklahoma. Baker’s grandmother, Stella Whiteturkey Fugate, owned land in the Osage reservation in Oklahoma on which oil was discovered. She was murdered by poison in 1924. Baker says she was killed for oil during the Reign of Terror.

“Illegal land sales and land grabs were happening to seize allotment lands which were oil producing,” he said.

“Never Broken” is designed to use contemporary Indigenous art to seize control of Lenape history. Part of the exhibition features a set of historic paintings depicting the 1683 meeting of William Penn with Lenape chief Tamanend to agree on a treaty between the Lenape and European colonists.

Artist Benjamin West famously painted the scene in 1772, which was reproduced widely as prints and even on collectible dishware — a cup and saucer circa 1820 are on display. Another artist, Edward Hicks, kept painting that scene, which he called Peaceable Kingdom, over and over for many years.

But the scene of the Treaty of Shackamaxon, aka William Penn’s Treaty, is largely a historic invention. What exactly Penn and Tamanend agreed upon, and when exactly that agreement happened are not recorded in primary documents. The details of the presumed amicable arrangement exist mostly in paintings imagined by descendants of European colonists.

Baker said “Never Broken” is responding to the persistence of that imagined history.

“It’s pushing back against the myth of the foundation and formation of the United States of America,” he said. “The power of art to be the voice of contemporary expression is very, very important to this conversation.”

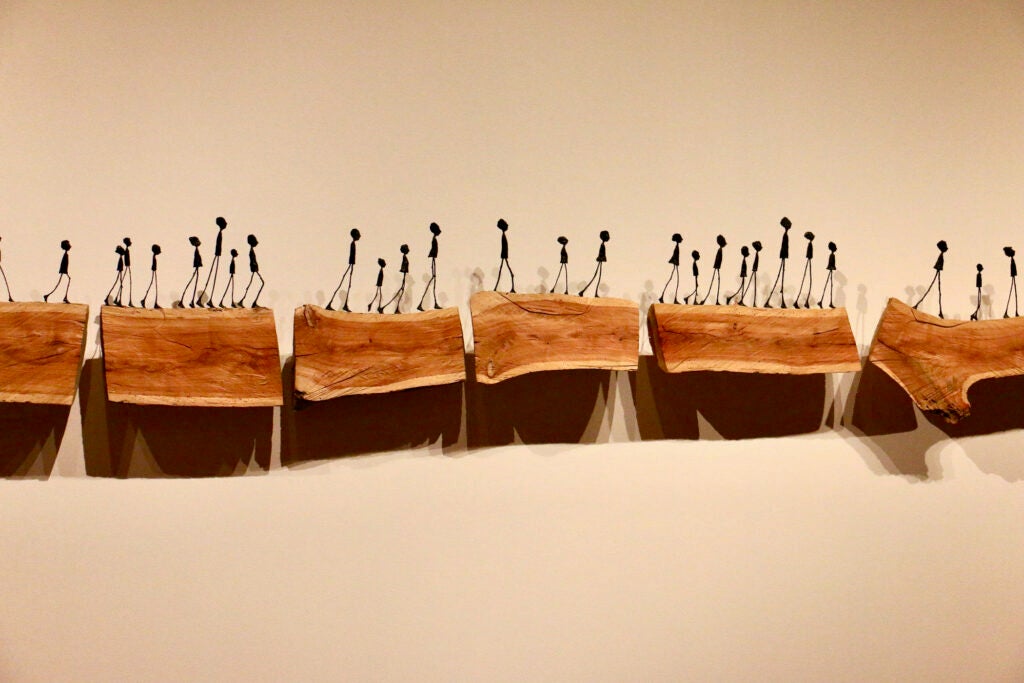

The exhibition also includes a large wall sculpture by Holly Wilson, “Bloodline,” featuring a long line of small bronze figurines, resembling stick figures, walking along pieces of a split locust tree. The piece comes out of Wilson’s research into her family genealogy, and her desire to give form to the people she was discovering in records.

“Never Broken” also features a video work by Nathan Young, who recorded himself walking a portion of the Walking Treaty, an agreement made by William Penn’s sons to occupy as much Lenapehoking land as a man could walk in a day. However, Penn’s descendants cheated the Lenape by using fast runners, instead of walkers, to stake out the land.

“Never Broken” will be on view at the Michener Museum until Jan. 14.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.