How do we predict flooding, and what can we do about it?

The worst of the flooding brought by Tropical Storm Isaias may be over. But it serves as a harbinger of what could come next time.

Listen 1:00

Alfredo Salce records footage of the auto shop he works at nearly under water on Colwell Lane in Conshohocken, Pa. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The worst of the flooding brought by Tropical Storm Isaias may be over. But it serves as a harbinger of what could come next time.

When the storm swept through the mid-Atlantic Tuesday, it left power outages, destroyed buildings, and submerged streets in its wake. And although all tornado watches and flash flood warnings were canceled by evening, the Philadelphia region continued to watch the water rise. The city’s Eastwick section was driven underwater yet again. Lansdowne and Upper Darby were covered in mud.

Creeks and rivers in the Delaware River watershed surged to record-breaking heights. In Montgomery County, a stretch of the Perkiomen Creek near Graterford rose to 19.14 feet, surpassing its previous 1935 record by nearly a foot. In Lehigh County, rain from Isaias inundated Allentown’s Jordan Creek until it rose to 11.82 feet, breaking its previous flood record of 11.6 feet set in 1972 by Hurricane Agnes.

Not 1, but 2 flood of records have occurred from the rainfall brought on by Isaias. pic.twitter.com/lezPu538Z8

— NWS MARFC (@NWSMARFC) August 5, 2020

The Schuylkill River meets the Delaware in Philadelphia, but it starts more than 100 miles to the northwest, flowing through Schuylkill, Berks, Chester and Montgomery counties before reaching the city. That flow, combined with the dozens of tributaries that run into the shared watershed, means the worst of its storm-driven flooding can start outside the city, too, which can spell catastrophe.

In 2018, Pennsylvania’s Emergency Management Agency documented about $163.5 million in public infrastructure flood damage. Only about $62 million was covered by federal disaster aid, meaning the remaining $101.5 million in damage had to be absorbed by municipalities, counties and state agencies.

Not included in those numbers are the millions of dollars in damage sustained by the owners of private homes and businesses.

And things are only getting worse. Randy Padfield, PEMA’s acting director, told State Senate committees last year that the frequency and intensity of precipitation events in the northeastern United States have increased by as much as 74%, creating a similar increase in flood damage. And over roughly the last 25 years, the vast majority of flooding reports have been outside established flood zones.

Where are those flood zones, exactly?

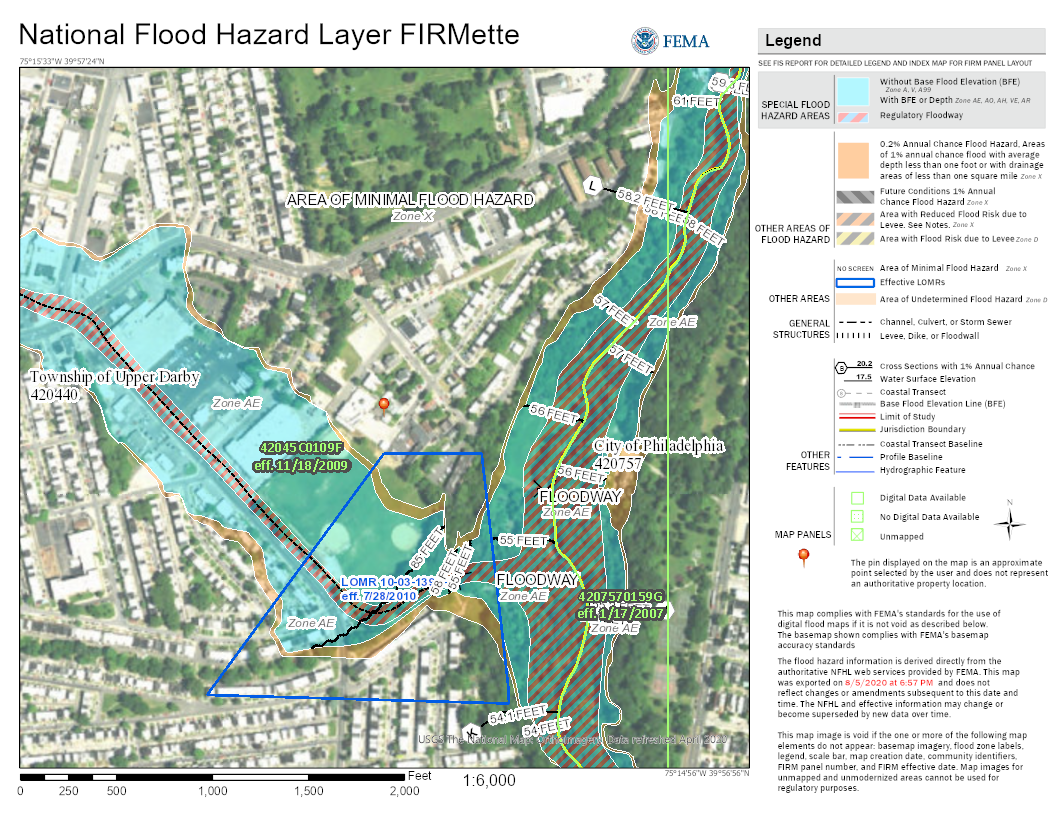

Maps available publicly from the Federal Emergency Management Agency indicate which areas of the Philadelphia region are most susceptible, designating special flood areas and future flood risk zones.

The flood maps indicate 69th Street in Upper Darby as a danger zone, for example; striped blue zones are regulatory floodways, while zones in blue are designated special flood hazard areas and zones in orange are areas that could potentially be at risk from more severe storms.

But some Upper Darby residents and business owners, devastated by Isaias’ impact, say they weren’t previously aware of the area’s history or risk for flooding. In the absence of either hazard warning or stormwater management, they say, they’re paying the penalty.

You can look up your area’s level of hazard here.

Even FEMA flood risk maps rely on a limited set of data, said Christiana Pollack, a hydrologist and project manager at Princeton Hydro, an environmental services and engineering firm. Shifting climate, changes in precipitation and water flow, the age of the data used, and even the underlying topological information on which the map is built can affect researchers’ ability to accurately predict floodplains and hazard zones. That’s why waterways like the Perkiomen and Jordan creeks may appear to flood beyond expected boundaries.

When doing flood analysis and mitigation, researchers start by examining past effects. “The residents in the area usually have a strong memory of what storms have hit the most hard … you can tie their history and memory with the weather record,” Pollack said. “How much rain fell? How quickly did it fall?”

Once a location’s history is understood, it’s a matter of balancing that with future predictions. Particularly severe storms might surpass National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration criteria for 1% annual chance weather events, commonly referred to as “100-year storm events,” which are hypothetical scenarios used to calculate potential future hazards. “Five hundred-year storm events” are even less likely, so scientists might avoid planning extensive and costly mitigation efforts around them; still, Pollack said, in the event that they do occur, their effects could be catastrophic.

“It’s very much a balance.”

What does climate change forecast?

Environment and weather researchers say that as climate change advances, the Philadelphia region will be hit by heavier, more frequent rains and storms. Globally, changing ocean levels will result in more destructive flooding in coastal communities, as well as along the tidal Delaware and Schuylkill rivers.

The ability to handle such weather catastrophes is critical.

Hiba Baroud, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Vanderbilt University, cited three factors: the increasing frequency of natural disasters, more dense urbanized populations, and a growing vulnerability to infrastructural failure.

“Infrastructure systems, especially in this country, were built a very long time ago, at a time where these kinds of storms were not as frequent — and so they were built to certain types of standards that do not apply today and will definitely not apply for future,” she said. “One failure could lead to the deterioration of many other systems.”

For example, Baroud said, a storm’s high winds could cause power outages. Power outages mean residents can’t charge their phones, which in turn means a loss of communication and network connection. But electricity also dictates the function of traffic and transportation systems, the distribution of water, the accessibility of heat.

“We cannot plan for infrastructure resilience and treat these different systems in silos,” she said.

That’s why, even as state and local governments reel from Isaias’ effects and work toward relief and cleanup, Baroud said, it’s essential to plan longer-term.

“No disaster is anything like the others, unfortunately … we continue to see events where we’re going to say, ‘Oh, I’ve never seen something like this,’ or “Oh, that’s the strongest storm I’ve ever witnessed.’ So when we’re planning for the future, it’s important not to plan for events that have already occurred. [You] have to account for the fact that these climate events will become more frequent than you think.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.