Three maps tell the story of urban farming in Philly right now

Philadelphia’s vibrant urban farming community faces new pressures as land values increase. Three maps reveal challenges — and opportunities.

A young girl works in a community garden. (Courtesy of VietLead)

Hundreds of Philadelphians grow their own food on city land. African and Southeast Asian immigrants cultivate African eggplant and Thai roselle in South Philadelphia. Mexican immigrants and Puerto Ricans grow jalapeños and gandules in Kensington. In neighborhoods across the city, some 418 edible gardens bloom across 500 parcels.

But these spaces face an uncertain future as development pressures encroach.

The areas where many of the edible gardens cluster — South and West Philadelphia and Kensington — are gentrifying fast and growers find themselves facing eviction from land no one else wanted until now.

As the city moves forward with a first-ever Philadelphia Urban Agriculture Plan, three maps created by Interface Studio, with data gathered by Interface and partners at Soil Generation, tell the story of where Philly’s urban farmers are now and where they may be in the future.

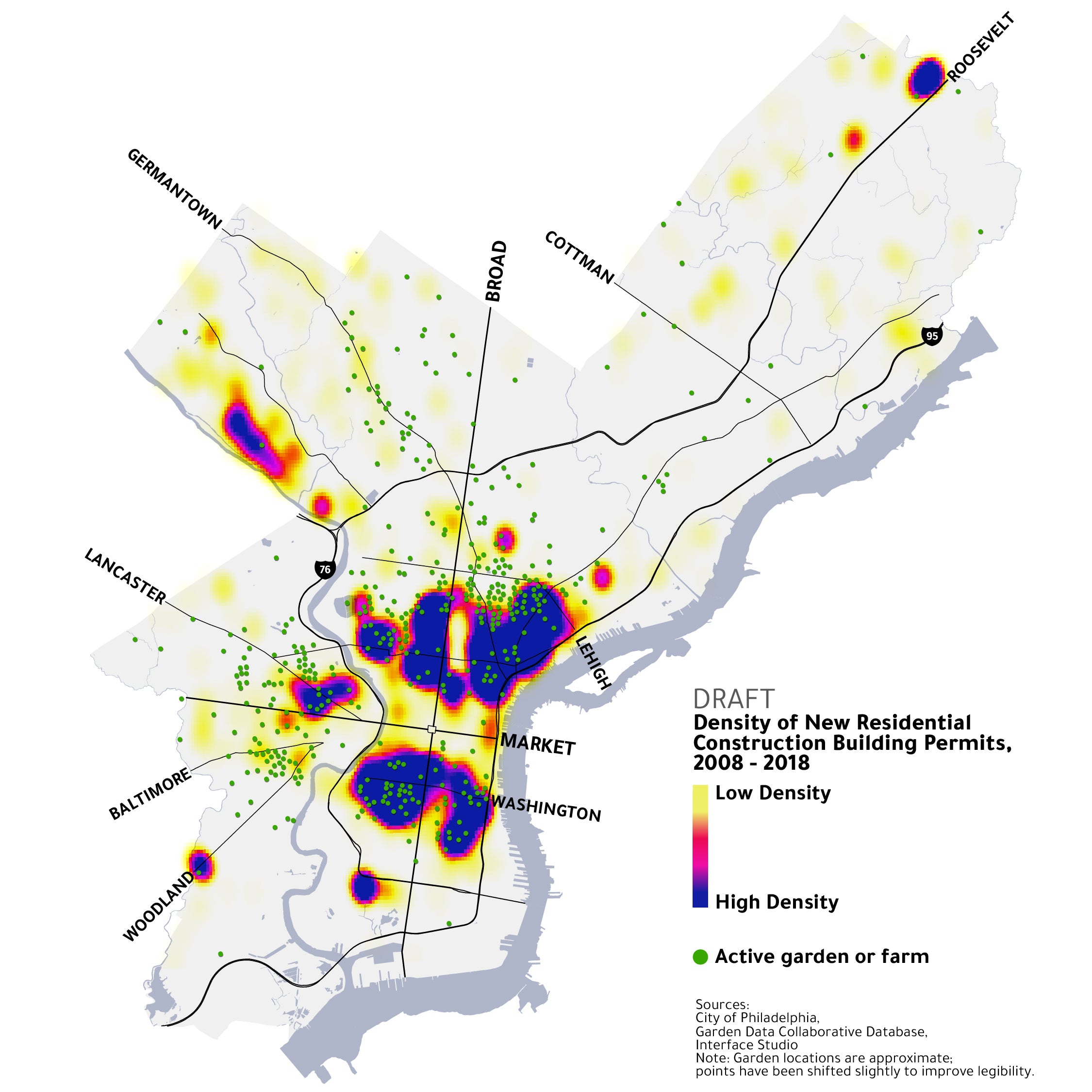

Threatened by development

Philadelphia lost at least 141 gardens and farms, according to the Philadelphia Garden Data Collaborative. Each disappearing farm has a unique backstory, but new development has replaced many of them.

Hundreds of gardens remain vulnerable because, often, the farmers don’t own the land they tend and do not have a clear route to ownership. By crossing the city data of building permits for new residential construction and existing gardens, Interface and Soil Generation found that one in three active farms could be threatened by gentrification in areas such as Point Breeze, Pennsport, Fishtown, Port Richmond, Norris Square, Brewerytown, Francisville and Manayunk.

“Most places where gardens are being threatened are in places with higher development pressure,” said Kirtrina Baxter, an organizer with Soil Generation.

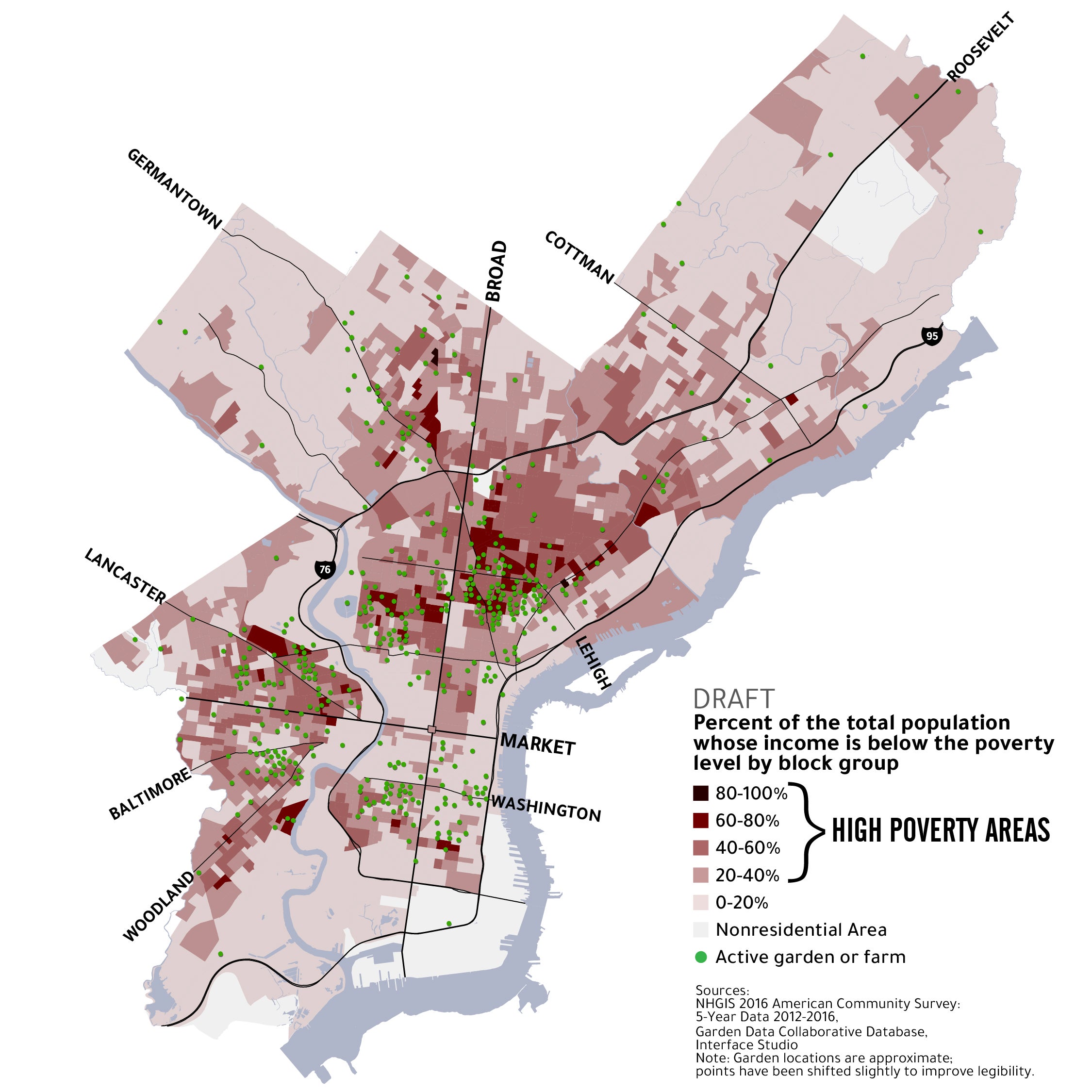

Clustered in neighborhoods without many options

Sixty-seven percent of the active gardens or farms in the city bloom in areas where poverty rates run higher than the city average and more than half of households are Black, Latinx or immigrants and have little access to high-quality food.

“The gardens are showing up in areas of high need and people are taking autonomous practices and growing their own food because they need it,” said Ash Richards, Philadelphia’s urban agriculture director.

Yet the need for edible gardens remains far from met. Draft data collected by the city shows that only 20% of those living in areas without much access to high-quality produce live near an active garden or farm.

“These maps are showing us the gross gaps of food inaccess for areas of high poverty,” Richards said. “So what do we do to address that? At this moment in time, we know that it can’t be fixed by the private market supermarket, so then what else? I think urban ag fills in a lot of gaps.”

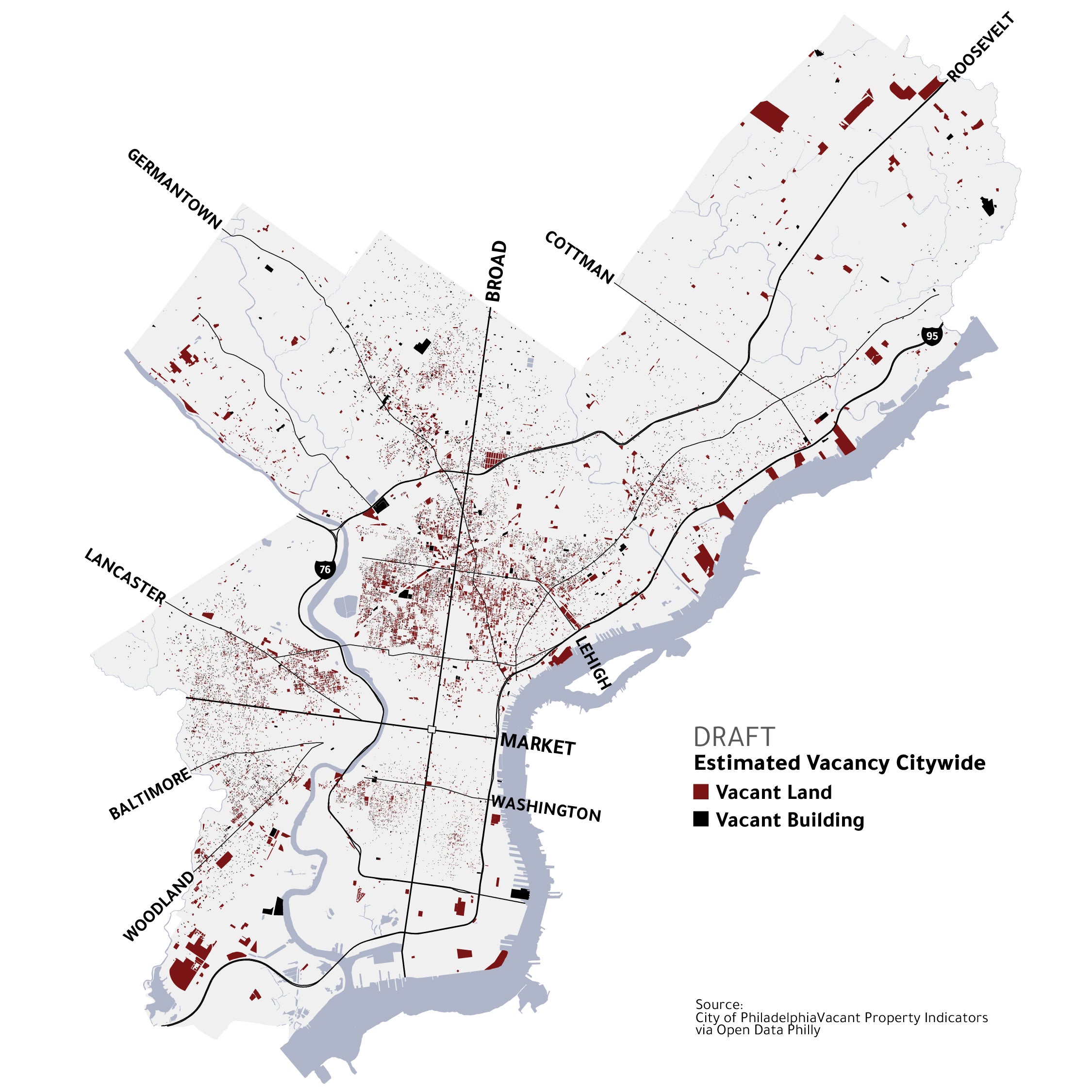

Opportunity to grow

As development pressures squeeze growers in some parts of the city, other areas offer fertile opportunity. There are 3,000 acres of vacant property in the city. Out of 42,100 vacant lots and buildings in Philly, about 6,000 properties are publicly owned and available to hand off to an agricultural-minded owner.

Richards sees a lot of social and economic benefits in transforming empty lots to grow food.

The city could produce more of the food it consumes without the need of trucking it from all across the country, Richards said, and that kind of development could create local jobs, increase access to quality food and reduce waste.

“I definitely want to see in the future our city preserving and creating more farms,” Richards said. “I think every neighborhood in the city should have farms and community gardens.”

Correction: This article was corrected to attribute the fact that 141 Philadelphia gardens and farms have been lost to the Philadelphia Garden Data Collaborative. The fact was also updated to reflect that the collaborative does not know the time frame in which the sites ceased operations.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.