‘Bellwether for the city’: Housing advocates say luxury townhomes in South Philly violate legal agreement

The developer of St. Anthony’s and Artist Village argues his company is in the clear.

Listen 2:00

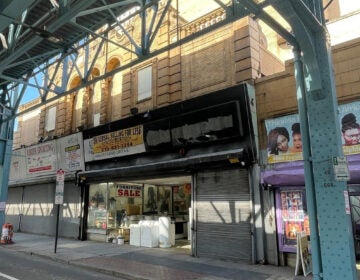

With the parking lot gone, Birchwood resident June Burris sometimes struggles to find a spot in her crowded South Philadelphia neighborhood. Since her landlord took away the parking lot that she and other residents used, her car has been vandalized twice. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Have a question about Philly’s neighborhoods or the systems that shape them? PlanPhilly reporters want to hear from you! Ask us a question or send us a story idea you think we should cover.

Near the edge of Graduate Hospital sits a former school building that retiree June Burris loved to call home.

Burris moved to St. Anthony’s Senior Residence in 2011 because she was living on disability benefits at the time, and federal tax credits secured by the developer made the building affordable. She also liked that St. Anthony’s had off-street parking and grassy grounds, rare amenities for an apartment building in South Philadelphia.

“The back of the building, you had an area where you can have picnics or whatever. You had benches outside,” Burris recalled. “It just seemed real cozy.”

The building’s appeal has faded recently, however. Roughly two years ago, the owners of St. Anthony’s began building a row of luxury townhomes on part of the property’s parking lot. Tenants were barred from using the lot and made to park on the street. Burris, who lives on a fixed income, has seen her car broken into twice since then, forcing her to replace two windows.

Burris, 68, has also had to contend with construction-related noise for several hours each weekday. The townhomes, which are being marketed for more than $1 million online, sit just beyond the living room wall of her tidy apartment.

There’s also a broader, more troubling issue with the new development, affordable housing advocates say. Public records show the townhomes may violate a legally binding agreement the property owner signed decades ago requiring the project remain affordable until 2032. That means the project could draw civil litigation as the city continues to search for ways to expand its limited stock of affordable housing.

Advocates are raising similar concerns about another affordable project the same developer built in the neighborhood a few years before St. Anthony’s — concerns the developer says are unfounded.

Burris finds the whole situation appalling.

“They’re not putting signs saying, ‘You’re not welcome. That one’s not welcome.’ But they’re doing it with the dollar sign,” she said.

Competing interpretations

These days, Graduate Hospital is a majority white neighborhood and one of the wealthiest in the city. But in 1998, it was a working-class Black community with a fair share of vacant properties and drug dealing.

That July, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority acquired the St. Anthony de Padua Parish School, a vacant five-story brick building on Carpenter Street, less than a mile from the Schuylkill River. The agency also took control of several additional parcels on surrounding streets.

Later that year, PRA selected Ingerman Regis Corp to create 53 affordable rental units by renovating the school and a group of existing rowhomes. To finance the $6.1 million project, Ingerman secured a pair of loans and leveraged Low-Income Housing Tax Credits from the federal government.

Accepting the tax credits meant the project had to remain affordable for 15 years. The Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency, which issued the credits, also placed a restrictive covenant on the development requiring the “project” to remain affordable for a total of 30 years, according to documents obtained by WHYY News.

In addition, a provision of the covenant, a legally binding document, requires the owners to allow tenants to remain in their units for another three years at the same rate.

After that, Ingerman would no longer be obligated to keep the development affordable.

While a judge may find the restrictions only apply to the building, affordable housing advocates argue the restrictive covenant applies to the entire St. Anthony’s development — the building, the grounds and the parking lot where 10 luxury townhomes now sit. That would mean Ingerman jumped the gun by about seven years.

Dina Schlossberg, executive director of Regional Housing Legal Services, called building the townhomes a “gross violation” of the covenant. And she’s concerned Ingerman’s actions could deepen Philadelphia’s affordable housing crisis if the PHFA elects not to enforce the terms of the indenture.

PHFA is the only entity with the ability to take action against Ingerman, though impacted residents could sue privately.

“This is a bellwether for the city,” said Schlossberg. “If he doesn’t have to [comply with the restrictive covenant] then why do others have to?”

Schlossberg said her organization has never seen a property owner use a portion of a site covered by a tax credit transaction to build a market-rate development — without first getting consent from PHFA.

CEO Brad Ingerman said his company never needed permission from PHFA to move forward with construction. The restrictive covenant, he said, only applies to the apartments at both sites, meaning the luxury townhomes don’t violate the agreement.

If the opposite were true, he said, red flags would have gone up.

“We not only had the title companies that were ensuring title for owners of these homes take the position that there was no restriction that applied to the land, but we also had two different lenders and two different lawyers representing those lenders that took a similar position that the land was not subject to any restrictive covenant,” said Ingerman.

Maximizing profits?

In November, City Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson penned a letter to the executive director of PHFA. The document, obtained by WHYY News, details the circumstances at St. Anthony’s — now called Birchwood at Grays Ferry. It also covers concerns the veteran lawmaker had with a separate luxury development on the grounds of Artist Village, another affordable housing project the city chose Ingerman to develop in Graduate Hospital in the 1990s.

“Such blatant disregard of the terms of a legal contract deserves an equally strong response from PHFA that makes whole the tenants of these projects and captures these ill-gotten gains to support affordable housing in the immediate neighborhood, where affordable options are in short supply,” wrote Johnson, whose district includes St. Anthony’s and Artist Village.

Artist Village sits near the corner of 17th and Bainbridge streets, less than a mile away from St. Anthony’s. It consists of two buildings with a total of 36 units. And like St. Anthony’s, the project received Low-Income Housing Tax Credits that prompted a nearly identical restrictive covenant from PHFA, which also refers to the development as the “project.”

In this case, the covenant expires in 2028.

Ingerman is building 14 new townhomes on the site, replacing an entire parking lot and open space part of the site. The townhomes are being marketed for nearly $2 million. The development also includes a new 20-unit building that is physically attached to one of the affordable ones.

Ingerman obtained building permits for both sets of townhomes before the end of December 2021, according to city documents. The timing is significant. Any building permits dated after that deadline were automatically subject to a new iteration of the city’s controversial tax abatement program that requires property owners to pay more to the city over the first 10 years.

Under the latest version of the program, the value of the abatement gradually reduces over time. Before now, the abatement enabled developers and homeowners to avoid paying taxes on any new or rehabbed property for 10 years.

In his letter, Johnson said Ingerman moved forward with the developments when the company did in order to maximize his profits.

Veteran zoning attorney Darwin Beauvais said the restrictive covenants in place for St. Anthony’s and Artist Village would not have stopped Ingerman from obtaining building permits.

“If an application is submitted for a zoning permit or a building permit, and the application follows what’s required under the code, a permit will be generated, unbeknownst to any other policy issue. This is not to take away from [Licenses and Inspections], it’s just that that’s what our permitting office is made to do,” Beauvais said.

Now Council President Johnson is pushing PHFA to take a series of remedies. He is calling on the agency to extend the restrictive covenants at both properties by 30 years; compensate tenants for the loss of parking; and compel Ingerman to use any “windfall profits” from the projects to support additional affordable housing, among other recommendations.

Through his spokesperson, Johnson declined an interview request.

In an email, PHFA spokesperson Scott Elliott said the agency is “reviewing the situation involving these properties.”

“Final decisions on any action are still pending,” Elliott said, “and we do not have a timeline as to when we may, or may not, take action.”

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.