Salem, New Jersey residents to decide who should deliver their drinking water

Salem residents will vote on whether New Jersey American Water should take over the city’s drinking water system.

Listen 4:56

Douglas Frost turns on the tap in his Salem, N.J., home. He doesn't trust the water, but he fears privatization will only make it more expensive. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

There’s been a competitive door-knocking campaign in the small city of Salem, New Jersey.

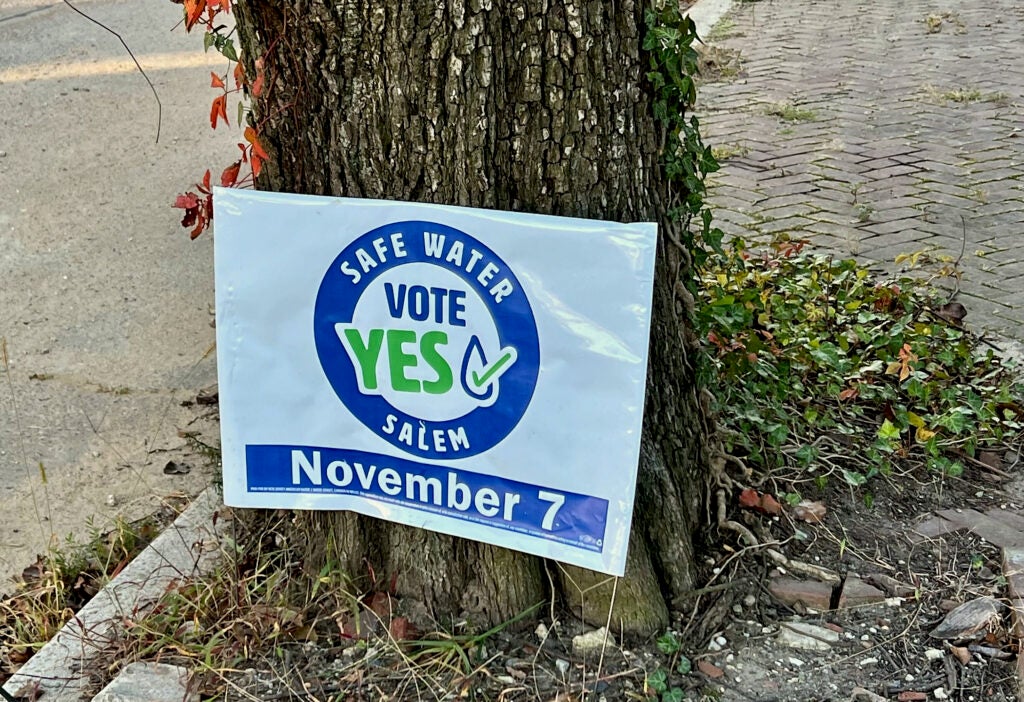

Volunteers have handed out leaflets and assembled yard signs throughout the South Jersey community to prepare for Election Day.

The effort was not for a political candidate, however, but for a battle over water.

When Salem residents head to the polls on Tuesday, they will vote whether the town should sell its water system to New Jersey American Water, a subsidiary of the largest investor-owned water utility in the U.S.

If successful, the sale would become one of more than two dozen similar transactions by investor-owned utilities across the region in the past five years.

Salem city officials say they’re struggling to make ends meet — industry has left, and the city’s main drag is lined with boarded-up vacant buildings. The city is facing an $11 million debt, and officials say they have no choice but to sell their drinking water.

They’re also grappling with toxic PFAS chemicals, which could set the city back $1 million to clean up. The “forever chemicals,” found in numerous household products and firefighting foam, are linked to serious health problems, including some cancers. Last year, one well in Salem contained PFAS levels above state standards and has been shut down ever since.

“PFAS can show up any time, anywhere. And if it happens again before we get this filtration system on, it’s going to be a bigger issue,” said Salem Mayor Jody Veler.

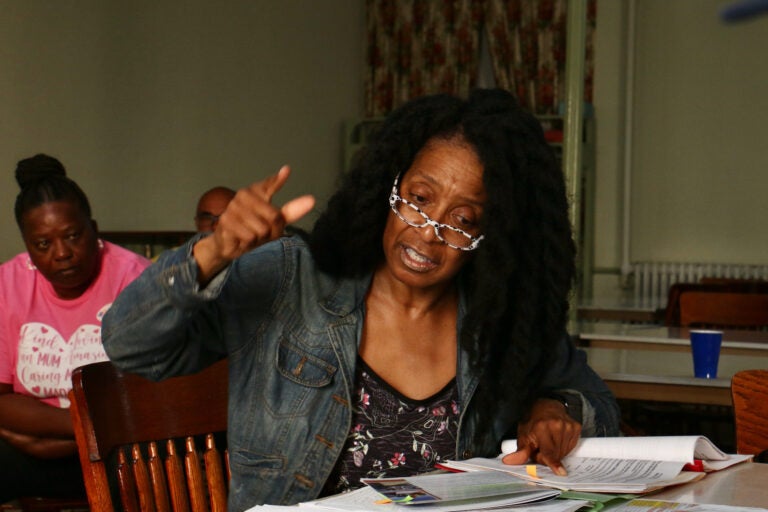

But residents such as Janice Roots don’t buy it — arguing constituents shouldn’t be forced to pay for the city’s “poor financing decisions.”

“This has nothing to do with the PFAS in our drinking water. They don’t give a crap whether the PFAS problem gets fixed or not,” said Roots, who is leading a grassroots campaign against the measure. “They want to settle the debt in this city that they created.”

Roots, with the help of nonprofit Food & Water Watch, collected 250 resident signatures to petition the city to place the decision on Tuesday’s ballot.

The referendum has led to a campaign that rivals any small-town political election. A large billboard promoting the sale greets drivers as they enter the city of only about 5,300 residents. The debate has become so heated, some residents against the measure allege their yard signs have been stolen.

Those in favor of the sale believe New Jersey American Water will provide clean drinking water. Those opposed worry the company will raise rates in Salem, where the median household yearly income is $26,000.

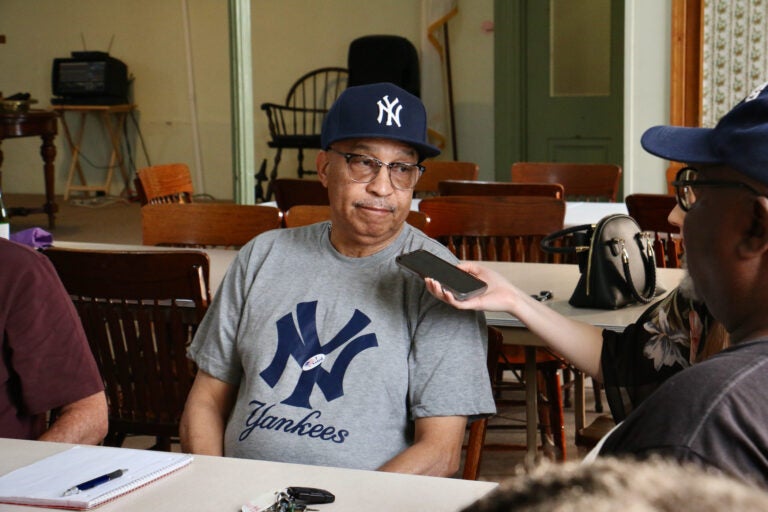

“I’m not making a whole lot of money,” said Otto Batemen Sr., 78, whose sole income comes from performing in a rhythm and blues band. “And with the groceries, rent — and then you got these stores around here just pushing up prices because they want to.”

A history of financial struggles

Mayor Veler said the city’s financial woes began long before she was elected in 2022. Around 2010, the city took out a state loan for a water system that would, in part, transition the supply from well to surface water. However, the system failed, which led to a settlement with EG Power & Water and other contractors for a poorly designed filtration system.

“The city has a long history — and I’m not blaming anybody in the past, everybody made the best decisions that they could make. But we’ve been unable to manage this system for quite some time,” Veler said.

The city’s water and sewer system also has a deficit, which City Administrator Ben Angeli blames on decreasing commercial customers. He said the water system also needs significant costly upgrades, such as refurbishing its water tower, building a PFAS filtration system, and replacing aging water meters.

The city is not alone — acquisitions of municipal water supplies by investor-owned utilities are increasing across the U.S., utility experts say. Infrastructure is aging, and many municipalities can’t afford the upkeep required to meet drinking water standards, or address the impacts of climate change such as increased flooding and drought.

A 2018 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency report estimates public water systems across the U.S. need $472.6 billion in infrastructure investment over the next two decades.

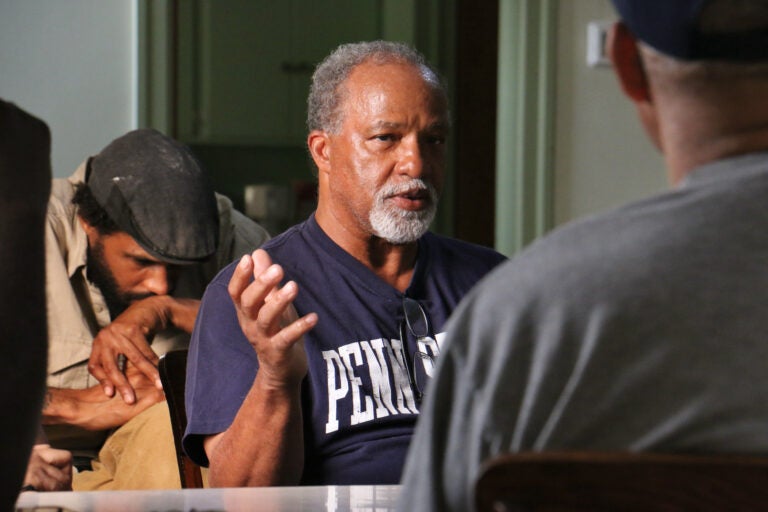

Investor-owned utilities have an advantage over municipalities because they receive returns on their investments, said Howard Neukrug, executive director of the Water Center at the University of Pennsylvania. Public systems would need to raise water and sewer rates about 12% a year to replace pipes and filter PFAS, and invest in the future.

“We’re coming to this point where there’s this big investment need … and they can’t get enough money from the rates because the rates are kept artificially low for political reasons often,” he said. “So you can’t do what needs to be done.”

Federal funding for water systems also has fallen by 77% in real terms since its peak in 1977. That’s partly because funding from the Clean Water and Safe Drinking Water Acts have shifted from grants to loans, said Peggy Gallos, executive director of the Association of Environmental Authorities, a New Jersey trade association for publicly-owned water, wastewater, and solid waste utilities.

And there’s greater incentive for investor-owned utilities to acquire public water supplies, Gallos said. Several states have passed fair market value laws, which allow companies to consider the future value of a utility, pay above that price, and then pass along those costs to consumers, she said.

Through the third quarter of 2023, American Water closed on 14 acquisitions across six states, adding 7,900 new households and businesses. At the end of September, the company had 32 transactions under agreement across 10 states, reflecting another 88,100 households and businesses. Seventy percent of these acquisitions and transactions were for municipal water, according to a company spokesperson.

A Cornell University study of the 500 largest community water systems in the U.S. found that privately owned systems have higher annual bills and lower affordability. According to the report, New Jersey and Pennsylvania have some of the highest in the sample.

“They’re just more expensive because their customers have to support that return on investment,” Gallos said.

Mark McDonough, president of New Jersey American Water, called those assertions “false.” If the sale in Salem is successful, the company will implement a two-year freeze on rate hikes. There would be a 3% increase over the next three years, however. But McDonough said New Jersey American Water has assistance programs for customers struggling to pay their bills.

McDonough argues that investor-owned utilities are held accountable, because they must seek approval for rate increases from a public utilities board that considers potential impacts on customers.

“Our rate increases tend to be very controlled, unlike what you see in municipalities — where they can raise rates without review by anyone other than the city,” he said.

Salem raised water rates by 25% in July, and back in 2012, rates were raised by 55%.

Residents grapple with whom to trust

American Water must gain the trust of residents in Salem, who say they’re frustrated by the city’s “poor management” of the water system. The aging meters have a history of providing false readings, which has led to some residents underpaying what they owe.

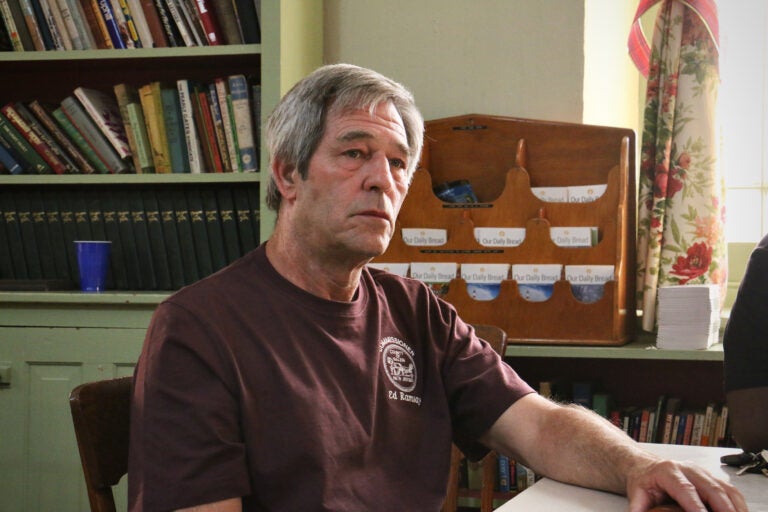

Other residents say they’ve been hit with surprise water bills. Douglas Frost, 73, received a bill for $1,300 this year — double his usual bi-yearly payments.

“They didn’t show me any paperwork. They just showed me the end figure of the 13 plus. And anybody would be a little aggravated at that,” said Frost, who’s voting against the sale.

Renters also say they’ve faced water shutoffs in recent months. Ambriona Thompson said her disabled father and grandmother, whose utilities are included in their rents, lost their water connection for 48 hours without warning last week.

“My grandma cannot be in my house, because she’s disabled and can’t do steps, and I have a lot of steps in my home. So, there was really nowhere for them to go,” Thompson said.

City Administrator Angeli said the city has hired an employee to address meter and billing issues, and that the city is committed to adjusting incorrect bills.

Some residents say they believe the sale is the culmination of “inefficiency” and “misspending” among Salem officials. Instead of handing over their water to a company, they believe constituents should hold the city government accountable.

Resident Craig Maue said he simply doesn’t trust American Water to have the residents’ best interests at heart.

“The American Water Company is a corporation with stockholders, and their primary thing is to make money,” he said. “I think the best way is to start paying attention to what’s going on in the city government … We could always vote new people in.”

But several other residents who spoke to WHYY News said they’re in favor of privatization because they don’t trust the city’s water, which they say often smells of chemicals and has a bad taste.

Ginny Jared said two of her daughters have lupus, and another daughter has a history of infertility issues. Jared, who owns a hair salon, wonders if PFAS is the cause.

“I’d rather pay for good water and good health,” she said.

McDonough of New Jersey American Water agrees his company is in a better position to provide safe drinking water and tackle significant challenges.

“There are always challenges … whether it be climate variation or other emerging contaminants other than PFAS,” he said.

What the future holds

If the referendum passes, American Water expects the sale will close in June 2024, and its first priority is to design and implement a PFAS filtration system.

Mayor Veler said the $18 million sale will help the city pay its debt, and focus on projects that improve the city, such as building a new community center.

If the referendum fails, City Administrator Angeli said it will be a “long haul,” but officials will find a way to move forward. A recent audit of the city’s water and sewer operations determined rates would need to increase about 68% to eliminate the deficit, though Angeli asserts taxpayers should “never have to pay” for it.

He said the city would work to install a PFAS filtration system with the help of the state’s Department of Environmental Protection.

“We have not ever stopped thinking about what we need to do should this referendum not pass,” Angeli said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.