On 60th anniversary, SNCC veterans reflect on the struggle to register Black voters in the South

SNCC emerged as a force in the southern civil rights movement through their involvement in Freedom Rides and voter registration campaigns.

Listen 8:59

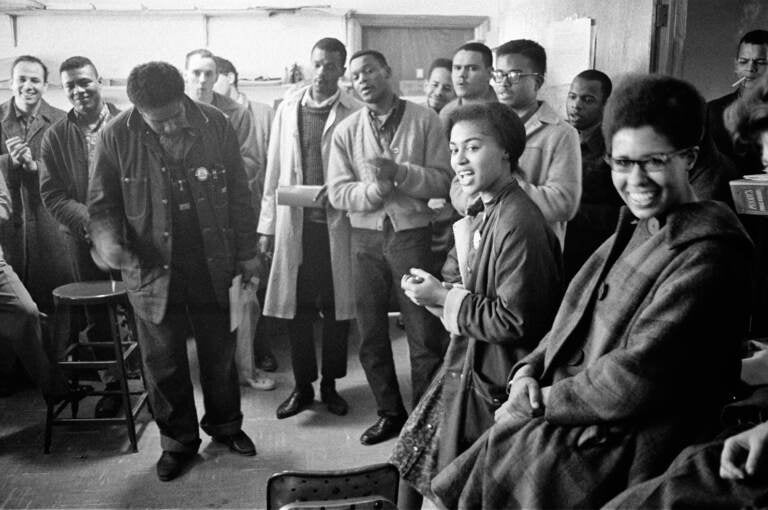

James Forman leads singing in the SNCC office on Raymond Street in Atlanta, (from left) Mike Sayer, MacArthur Cotton, Forman, Marion Barry, Lester McKinney, Mike Thelwell, Lawrence Guyot, Judy Richardson, John Lewis, Jean Wheeler, and Julian Bond, 1963, Danny Lyon. (Courtesy SNCCDigital.org)

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, was founded in April of 1960 by young people dedicated to nonviolent direct action tactics. Almost immediately, SNCC emerged as a force in the southern civil rights movement through their involvement in Freedom Rides and voter registration campaigns. During the 1960s, hundreds were arrested and many beaten, some killed. But they helped change America and turn young people like John Lewis into civil rights leaders.

Their work is not done. There is a renewed movement afoot that bridges the original generation of SNCC activists with the young leaders in the Black Lives Matter movement. SNCC turned 60 years old recently and is hosting a conference this week to further cement the cross-generational connection.

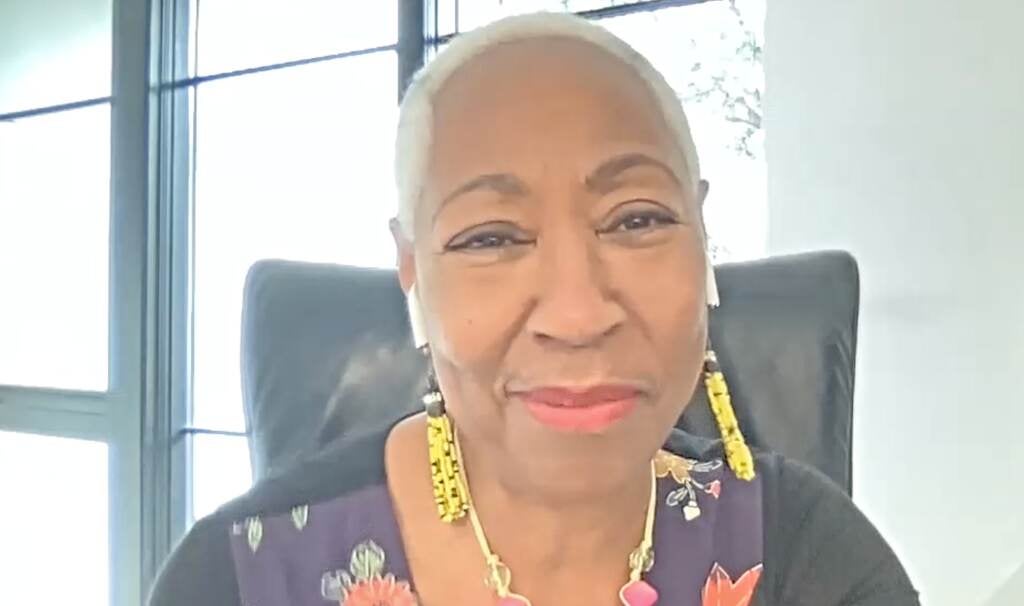

Judy Richardson began her activism as a student at Swarthmore College and went on to work in the SNCC National Office in Mississippi and in Alabama. Jennifer Lawson was just 16 when she joined the civil rights movement and became part of the SNCC as a student at Tuskegee University. Both are part of the 60th anniversary celebration.

WHYY Host Cherri Gregg sat down with Richardson and Lawson about their journey as activists and the passing of the baton to newer generations.

—

SNCC was a grassroots effort. Set the scene on how SNCC was able to inspire so many people and so many young people to risk their lives to help make change. And I’ll start with you.

Jennifer Lawson (JL): SNCC was started by students, and it was founded by Ella Baker, who was a remarkable woman who worked with the NAACP. But she felt “you students should have your own group.” And it was because students at that time, in 1960, were saying “I have had enough” and students started doing just very simple things, like sitting in at lunch counters of segregated places and saying, “No, I refuse to be asked to go down behind the store to eat. We demand that we should be served as human beings right here at this counter.” It brought together some incredibly brilliant young people from different schools, predominantly Black colleges and universities. But all over, those students then started saying, “This is about more than just food at lunch counters. Let’s look at how we can improve the lives of the African American community.”

I want to bring you in, Judy, to talk about this, because you were working in the organization. Nonviolence was a cornerstone. Can you explain why that was so important?

Judy Richardson (JR): We knew that we did not have the guns. Our main thing was, how do you get Black people registered to vote without getting them killed? And we knew that the state government, the local government — all controlled by white people — and the federal government, they were not going to support us. And what we had to do was be able to organize at the grassroots, with the Mrs. Hamers and the Mrs. Blackwells, throughout the Deep South in the rural south. But if you reacted with guns, they would shoot you down. They would kill what you were doing and everybody who was around with you. And your larger responsibility was to the people that you were organizing with. At the same time, it was the rural south. So there were people who definitely defended themselves who were local.

I read some of the transcripts, Jennifer, about being in these spaces knowing that your life was on the line. How did that impact your life and what did that do to you as a young person? People died in this movement.

JL: Judy and I both know so many people who lost their lives because of their work in the civil rights movement. … A very concrete way in which it changed, dramatically changed, my own life [is] I was a student at Tuskegee and planning to go on to become a doctor someday. And that all went away when one of my classmates, Sammy Younge Jr., was killed in January of 1966. We would go out into the community to help register people in rural Macon County [in Alabama] to vote and … he was killed. And I thought to myself, “What’s the value of my education if I can’t even safely live in the state of Alabama?” So I joined many other students at Tuskegee who then started marching, demonstrating, continuing our work on getting out the vote, and … then some of us decided, “No, we’ll leave school and join SNCC and work full-time with SNCC in Mississippi and Alabama and Georgia to try to really change things.” And it’s one of the proudest accomplishments of my life that the work that we did really did make a difference.

What do you think was the critical thing that helped shift the minds of the people in power to help make the change?

JL: Well, I wouldn’t say that we were shifting the minds of people. For example, during this time. George Wallace, an avowed segregationist, was the governor of Alabama. We didn’t put our emphasis on changing George Wallace’s mind. Judy and I worked in Lowndes County. Where we went into Lowndes County, there were only four registered Black voters, because Black people had been so intimidated that they couldn’t register to vote. When we left Lowndes County, people had not only registered to vote, they had created their own political party. The Lowndes County Freedom Organization had had as a symbol, the black panther, and that was the first Black Panther [Party] emerging in the movement. In that way, they weren’t trying to change the minds of the people who were in power. They were trying to become the people who were in power. So later, the man who started the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, he became the sheriff and served as sheriff there for about 20 years.

So basically, it showed people how to pick up the reins for themselves.

JL: Exactly, exactly. It was about empowering people.

JR: But I would also just like to add to that that when Jennifer mentions George Wallace, you know, he cuts back on his segregationist… He vocally becomes less racist. But that’s only because there are Black people registered to vote. And in Alabama, he has to worry about these folks who are going to come to the polls on Election Day. Now, there were always white allies. I mean, there were wonderful people who really supported us and provided funding and provided their bodies, and some were killed in the process. But the main thing was how do you get Black folks organized so that white people know that we are a power to be dealt with? Part of the reason that you use the vote is because we don’t have Koch brothers money. But what we do have is our vote.

Yeah. And I want to fast forward to today, when you look at the movement, I mean, we saw the tragic murder of George Floyd. You know, we look at today, a lot is left undone.

JR : Yeah, we really do understand the importance of working with the young people, and it’s because we see ourselves in them. You know, as Jennifer said, we were the only youth-led civil rights organization working in the South back in the ‘60s. … And what we saw was brilliance. Part of that is seeing that brilliance in these young people, and they’re looking to us and we’re looking to them.

SNCC will be celebrating its 60th anniversary virtually. Tell us about this effort to bring the generations together and move forward.

JL: It will be a mixture of things. It’ll be a very thoughtful gathering where we look at the strategies and we consider the future, but it will also be a celebration as well. Throughout this whole pandemic, we have been meeting with young activists and organizers from across the country and with students from many colleges and universities. And it’s been so heartening to us that they are asking us to join with them, it gives me this great sort of sense of optimism about our future in this country.

It’s going to be fun too.

JR: Absolutely. And you know, part of what grounded SNCC was music. I mean, we had the SNCC freedom singers. They will be there again. Toshi Regan and Martha Redbone, Sonia Sanchez from Philly is going to be there on the artists’ session. But also, you know, we have the government people who have become elected officials because Black people are voting. The new activists. Nsé Ufot, who heads the New Georgia Coalition.

What do you hope people take from this conference as you move forward and work on that unfinished business?

JL: I hope that, individually, people take with them the sense that, whatever walk of life you’re in, each of us can make a real difference.

JR : So people, if they could just understand, it’s a long struggle. We may not see it in our lifetime, but if you do nothing, nothing changes. And I got to change it for the people who are coming behind me.

Thank you to Judy Richardson and Jennifer Lawson.

The SNCC 60th anniversary conference runs now through October 16. Details at sncc60thanniversary.org.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.