Philly graphic novelist explores the emotional roller coaster of hip replacement

Emily Steinberg, a painter and graphic novelist, believes comics are a powerful way to confront feelings and combat loneliness in medicine.

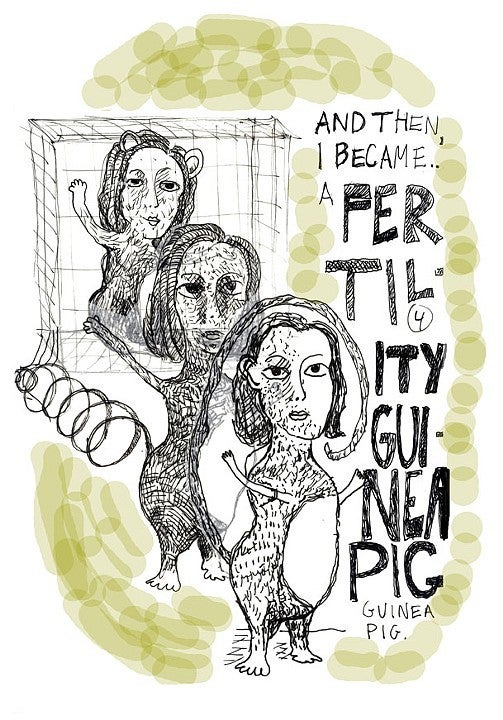

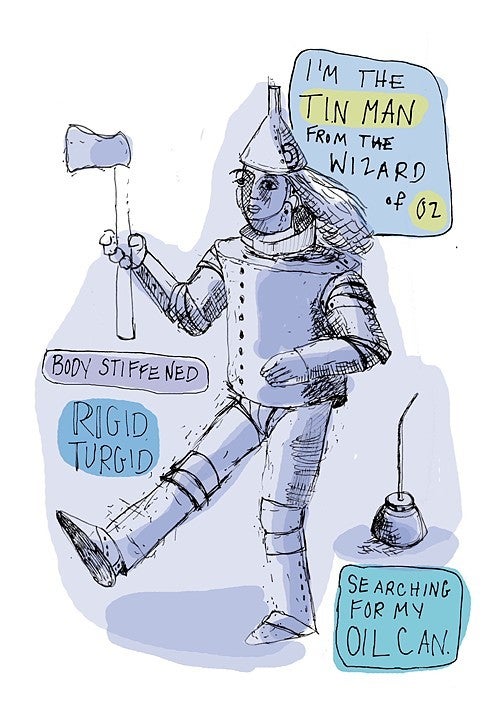

"Mid-Century Hipster" is about Philadelphia graphic novelist Emily Steinberg's experience of getting a hip replacement. (Courtesy of Emily Steinberg)

Diagnoses, surgeries, birth and deaths.

Many of life’s most intense moments happen in hospitals and doctors’ offices. A major medical event is perhaps one of the most universal human experiences. Yet it can also be one of the loneliest.

Emily Steinberg, a Philadelphia-based painter and graphic novelist, wants to address this — by bringing emotions more to the forefront in medicine.

Steinberg makes comics — or visual narratives, as she likes to call them — that grapple with events in her life, and the emotional ripples that come with them, many of which happen to be medical.

Medical experiences, she said, “are particularly evocative times in people’s lives. It’s a time full fear and hope and longing. It’s very dramatic. I think that lends itself really well to visual storytelling.”

Her latest comic recounts a recent hip replacement and was just published in the summer issue of Philadelphia’s Cleaver Magazine. “Six-and-a-half years ago, dancing like a 20-something freak at my niece’s wedding, my left hip snapped,” the story opens.

The work, called “Mid-Century Hipster,” is filled with panels of deep colors and rough lines sketching out feelings of fear, anxiety, depression, and, ultimately, triumph.

In one panel, a nurse, rendered in a saturated magenta, holds a larger-than-life syringe and seems to stare directly at the reader. In another, a post-op Steinberg droops toward the ground, as if she’s melting, struggling to walk to the bathroom in her hospital room. Often her panels have just one dominant hue, with accent colors for important words, or certain details, like the red hospital socks that stay with Steinberg through her recovery.

Originally trained as a painter, Steinberg broadened her practice to include autobiographical comics about a decade ago. She has created visual narratives that deal with depression, menopause, and infertility.

With “Mid-Century Hipster,” Steinberg said part of her motivation was that none of the step-by-step guides or informational resources she consulted prepared her for the psychological roller coaster of her surgery.

“I mean, it was scary. I was really scared. Just being surrounded by all these doctors with their masks and their headgear, it’s a lot of visual stuff to look at and process,” she said.

Not to mention, she added, “the whole idea of someone cutting into your body and taking out your hip joint with a saw, literally, and then putting something else in.”

A lot of emotional resonance came from little things, Steinberg said, which she highlighted in her comic — things like the weird disinfectant she had to shower with the night before the procedure, the jarring buzz of a hospital at 5 a.m. — making everything feel “like life or death, even though it’s not,” she says — and the angst of painkiller-induced constipation.

Visual storytelling as therapy

Making comics helps Steinberg confront her feelings about big life changes.

“I think my process is incredibly cathartic because I don’t really hold anything back,” she said. “It’s a good way to get to know who you are.”

She hopes to pass along comics as a therapeutic tool to others, too. Currently, Steinberg is the artist-in-residence at Drexel University College of Medicine, where she teaches visual storytelling to medical students and residents.

She believes having medical practitioners translate their personal experiences into words and images helps them work through their own sentiments and connect more with patients. One of her students, she said, used her course to process realizations about his privilege, which he came to after working at a clinic with many low-income patients.

“It allows them to kind of get into their whole mental-emotional space,” she said. “The medical profession can be very cut and dried, and it has to be on some level right? And I think that’s the inroads with graphic medicine.”

She also thinks that visual narrative lends itself particularly well to exploring feelings, calling it a cinematic art form.

Plus, people are drawn to combinations of images and words, she said, so the form fosters connection.

“When words and images are put together, that can be somehow even more powerful than either of them on their own,” she said. “It’s almost like there’s a spark that allows for double communication, that is incredibly energetic.”

The graphic medicine movement

Steinberg is not alone — she’s part of a movement, called graphic medicine, that is all about using visual narrative to tell medical stories. In the last decade, graphic medicine has gained momentum as a genre and community.

On the provider side, graphic medicine is a way to build empathy. On the patient side, it can demystify medicine and make navigating the healthcare system less scary.

Certainly, one of the central objectives of graphic medicine is “making everything more accessible and less freaky to people,” Steinberg said. “Let’s say you’re given a horrible diagnosis. If you can read something and say, ‘Wow, OK, people go through this,’ you feel much less alone. That’s comforting.”

“And that’s something I’ve heard over and over again about my own work,” she added. “People say to me, ‘I don’t feel like I’m alone anymore.’”

Steinberg is cooking up dreams of running a visual storytelling workshop with hospital patients. She’s also working on a new medical comic, “Gondolier in the Bathroom,” which is about her mother and dementia.

“It’s about what it does to the family. And what it does to the person,” she said. “It’s an incredible story, and it’s taken me forever to write it. My mother died 16 years ago. So I have not been able to do it yet, but it’s there and it’s coming.”

It has been a little over a year since Steinberg’s hip replacement. She said her new hip is performing very well — she walks five miles a day.

“Last year at this time, I would be lucky if I could walk from my bedroom to the living room without wincing,” she said.

She was also recently preparing to go to the doctor for an anniversary check-up.

“I’m going to bring ‘Mid-Century Hipster’ and show them,” she said.

Maybe it will create some dialogue between the patient and practitioner.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.