How backyard chickens blur the lines between farm animal and pet

In some cities, like Philadelphia, people run afoul of the law by keeping chickens. But back in the old days, it was the natural order of things.

Listen 11:03

Ms. V smiles at one of her chickens in her yard in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts.

For years, Ms. V wanted chickens in the backyard of her Philadelphia home. Her husband said no, and they never discussed it again.

Three years ago, when he passed away, Ms. V was not in a good place.

“I was very depressed, didn’t want to leave my house, didn’t talk with anyone.”

Six months later, a chicken escaped from her neighbor’s yard and came into hers. She gave the chicken back, but the chicken flew over a 7-foot fence and returned the next day. Her neighbor said he would either have to give the chicken away, or give it to her.

“It never, ever once dawned on me to say, give her away. I said, `I’ll keep her.’ And I named her Helen. So she was my first girl,” Ms. V said. “She gave me a reason to get up out of the bed every day.”

Ms. V had to learn how to take care of Helen: getting up in the morning to let Helen out of the coop, giving her fresh water and nutritious food. She also found the Philadelphia Backyard Chickens Facebook group, which has more than 2,000 chicken owners and enthusiasts.

She learned that chickens are social animals, so she got another one, named Sylvia.

“They were just like two little old ladies … one following the other. And then they just waddle and you will watch them walk across the yard. And it was just … awesome,” Ms. V said. “They’re my girls. They’re not just chickens. They’re my babies … they give me purpose to get up every morning and go outside.”

Ten months after Ms. V got Helen, a hawk attacked, and Ms. V found Helen in a corner with her eyes closed and the comb on her head wilted and pale. Ms. V didn’t see any wounds, but Helen was clearly not herself. She brought Helen inside to recover. Helen drank some water, her comb looked better, but she died the next morning.

Other backyard chicken owners advised Ms. V not to bury Helen as she would with another pet, because a raccoon or scavenger might dig up the body. Ms. V put Helen in a securely taped box in the freezer until the trash truck arrived.

“I couldn’t just put her in the trash can,” Ms. V said. “I got the box and put it in there in the truck myself.”

“Someone had asked me, well, why didn’t you eat the chicken? I have a hard time eating my pet,” Ms. V said. “If … your cat or dog dies, would you consider making a meal out of it?”

Subscribe to The Pulse

She still has Sylvia and three other chickens, Gladys, Rosebud, and Bella. They live in her yard, where Ms. V has a sturdy chicken coop, a holly tree, and a greenhouse that she says belongs to the chickens, though Ms. V will eat the greens she grows in there as well. The chickens do not seem at all afraid of humans, and they eat out of Ms. V’s hand.

Livestock Ban

Ms. V’s taking a big risk talking about them, because what she is doing is illegal. That’s why we’re not using her full name — Philadelphia does not allow its residents to keep chickens.

“Just talking with you could put me in jeopardy of having animal control come to my home and put a notice on my door and tell me I have three days to remove them from my property. And for each day that I don’t remove them, I get fined,” Ms V said. “Am I willing to go that far? Yeah. Am I willing to fight this to the end? Yeah … I am not going to surrender my girls.”

Philadelphia has a 2004 law that bans chickens and other farm animals because of the “nuisance and noise.” The City Council member who introduced the bill and the Animal Care and Control Team in Philadelphia did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Because of the law, said Maureen Breen, administrator of the Philadelphia Backyard Chickens Facebook group, “All of the group members live in fear of having their chickens reported.”

Philadelphia is an outlier from most large U.S. cities, which allow backyard chickens in some capacity. It classifies chickens as a type of farm animal, but they fall into this in-between place where they are now both livestock and pets.

That’s because the idea of what a pet is has changed.

Back in the 19th century, U.S. city dwellers practically lived next to horses, pigs, cows, and chickens, according to research from Catherine Brinkley, a professor of human ecology at the University of California Davis.

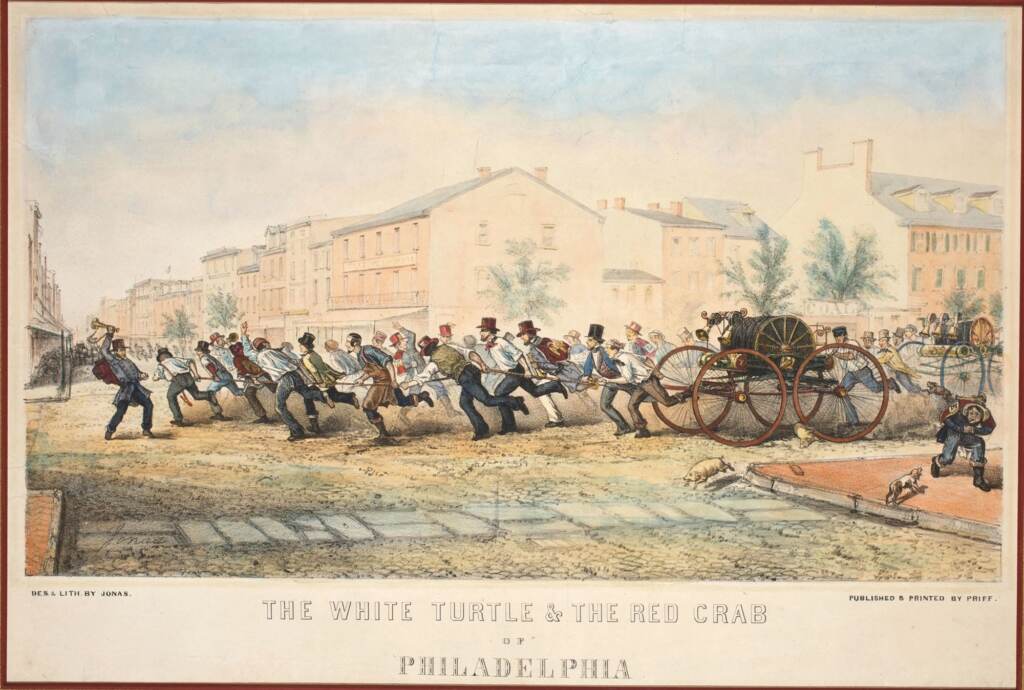

“Early cities had a lot of pigs running around, and if you look at lithographs, or early images of cities, you see pigs everywhere.” Brinkley said. “New York, there’s a famous painting … two hogs running around knocking people over. There are these wonderful lithographs of firemen … trying to put out a burning building in Philadelphia, and there were so many pigs that the artist drew a pig stuck under the wheel of the fire engine.”

Cities needed those animals because they provided food and infrastructure: Cows provided fresh milk, horses moved people and cargo, pigs ate garbage, and chickens provided fresh eggs.

But the people who lived in cities could hear, see, and smell the animals. So as cities got bigger, people began to turn on the animals.

Brinkley found that U.S. cities created boards of health in the 19th century to regulate animal agriculture. Public health ordinances then led to zoning regulations pushing slaughterhouses and dairy farms and piggeries first to poorer neighborhoods, and eventually out of cities altogether.

As urban livestock declined, pets became more popular, according to Andrew Robichaud, a historian at Boston University who specializes in 19th-century America and animal history.

The newly founded Society of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals promoted pets as a way to encourage kindness to animals. Robichaud said George Angell, who led the Massachusetts SPCA, “really thought that creating a new generation of Americans who are kind to animals would solve a lot of social problems … if we taught children to be kind to animals, they would be kind to one another.”

Now, across cities in the U.S., more people are becoming interested in urban agriculture, which brings cities full circle. Advocates want public officials to welcome chickens back in cities, but now with chickens that are not just sources of fresh eggs, but also, and maybe more importantly, companions and friends.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.