A codependent’s guide to codependency

When people are in unhealthy or unbalanced relationships, we often use a term to describe them: codependent. But what does that actually mean?

Listen 11:08

Many movies, like "A Star is Born," present codependent relationships as romantic ideals. (Warner Bros.)

When people are in unhealthy or unbalanced relationships, we often use a term to describe them: codependent.

I know this first-hand. Over the years, friends, partners, and therapists have told me that I struggle with codependency. But I never had a super firm grasp on what that meant, where it came from, and what I could do about it.

So this Valentine’s Day, I decided to take a closer look.

Searching for a definition

I started by asking friends why they think of me as codependent.

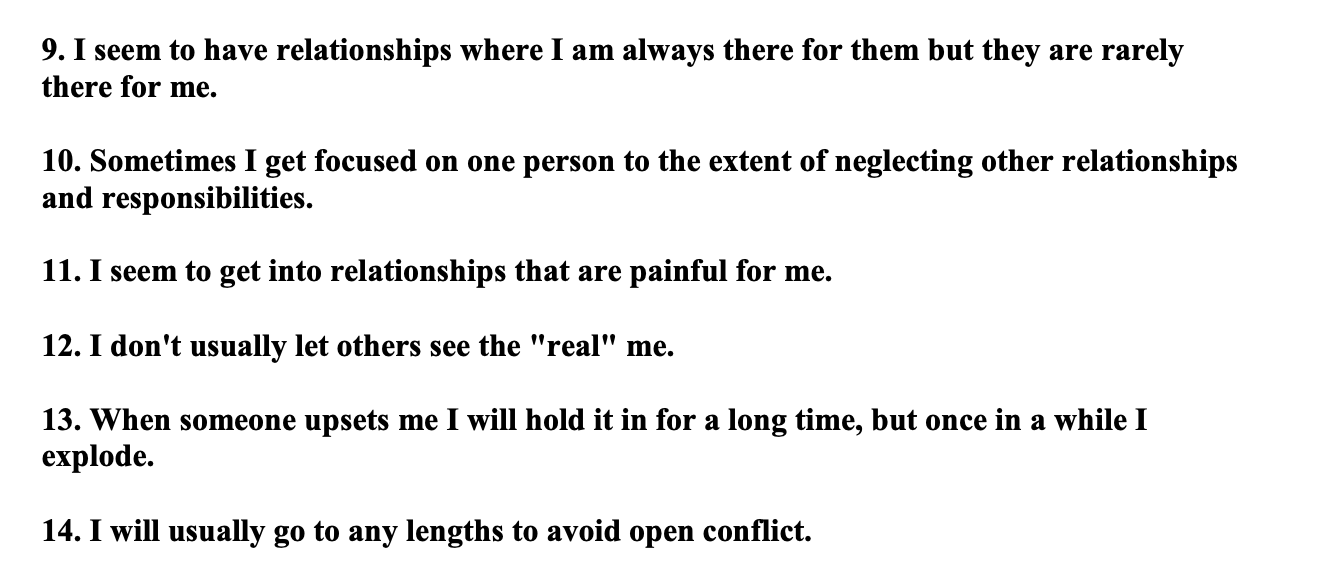

One friend, August Guang, told me that I jump into relationships too quickly. “You and the other person get in very, very deeply,” Guang said. “And prioritize each other in a way that I guess sometimes feels like shutting off the rest of the world.”

Another friend, El Sigelman, told me I’m conflict-avoidant, and a people-pleaser. “You sometimes will go against yourself, in order to maintain a level of pleasantness,” Sigelman said.

Lee Luke pointed out that I’m a caretaker, perhaps as a way of shunting attention away from my own needs and desires. “I think you often displace that with caring about other people,” Luke said.

My friends aren’t wrong. I do have a record of losing myself in relationships. I am a caretaker, and a wuss around conflict. Does that constellation of traits add up to codependency?

Next, I called up psychology researchers, therapists, and relationship coaches, and asked them to define the term.

“Codependent people live for others,” said Shawn Burn, a psychologist in California. “They don’t know where they end and others begin.”

“Codependents believe if they’re loved, then they’re lovable,” said Darlene Lancer, author of “Codependency for Dummies.”

“They end up doing a lot of caretaking — mostly with the intent to regain some control, and also for emotional validation,” said Misty Hook, a therapist in Texas.

In a codependent relationship, “your partner is your everything. Your best friend, the only person you can talk to, your entire system,” said Quinn Gee-Edwards, a therapist in Washington, D.C.

A lot of this resonated with me. But still, it felt imprecise. These sound like common struggles, especially at the start of a new romance, in relationships between young people, or if you’ve been socialized to think of caregiving and selflessness as good things — which a lot of us have.

Codependency is not an official mental health condition. It’s not in the big diagnostic handbook, the DSM. Yet it’s a term clinicians and researchers use all the time, and it resonates with so many people. Best-selling self-help books have been written about it. There are 12-step support groups for codependency.

It made me wonder, what’s the origin of this term? Why did it emerge in the first place?

Codependency and mental health

The concept of codependency arose in the 1940s and ’50s. At the time, psychologists and counselors were trying to understand how families and entrenched relationship dynamics shaped people’s mental health, particularly around addiction.

Researchers were finding that “they could take someone with an illness, put them in the hospital and treat them, and they would get better,” said Darlene Lancer, a marriage and family therapist in California. “But then they would go back to their family and get ill again.”

Practitioners started to realize it’s not enough to treat mental health conditions alone. You also have to treat relationships, or the interstitial give-and-take between people.

Many psychologists believe codependency is instilled early on. Through family dynamics and life events, children come to believe that their value comes not from their innate selves, but in how they can get others to recognize or accept them.

“Your focus, it’s outside of you,” Lancer said. “It’s something external to you, rather than being aware and attending to your inner loneliness and emptiness, or sadness, or anger — or whatever the feelings may be — and being able to comfort yourself and ask for what you want.”

For instance, children of people who struggle with substance abuse, mental health conditions, or chronic illness often learn that their value is in being a caretaker, or in keeping things together.

Codependency can also arise with parents or guardians who are emotionally absent, or rigid and controlling. Say a father doesn’t like that his son cries a lot and likes to write poetry. Lancer said that kid learns to suppress his feelings, and hide parts of himself to be accepted.

Tracy Davis-Black, a therapist in North Carolina, pointed out that codependency actually starts out as a coping skill. Codependents figured out a way to fulfill a need — for attention, care, or a sense of safety.

“It’s this pattern that has served somebody well in a lot of ways, and was really smart and adaptive in a way, to survive the chaotic family environment,” she said.

But over time, codependency can become a problem. And by adulthood, the programming is often lodged deep in. Particularly when it’s a response to trauma.

People often talk about “fight, flight, and freeze” as automatic responses to trauma. Now, some trauma theorists have added a fourth “F,” for “fawn,” Davis-Black said. It refers to people-pleasing, or submission, as a way to ease stressful situations.

Other psychologists have characterized codependency as a personality disorder, or as its own type of addiction: a love and relationship addiction.

Programs like Codependents Anonymous and Al-Anon, a support group for families and friends of alcoholics, take a 12-step approach to tackling codependency.

Cultural conditioning

But many experts say that codependency is about more than pathology. There’s also social conditioning to consider.

Take for example someone who’s naturally empathetic, and put them in a religious context that idealizes self-sacrifice. Could that lead to codependency?

What about socializing around gender? Society often teaches people to be women by teaching them to be nurturing and helpful, or to take a back seat to others, said Quinn Gee-Edwards, the therapist in Washington, D.C.

Gee-Edwards said the “strong Black woman” trope inspired her to publish a codependency workbook just for Black women, called “I’m Doing This For Me.”

“A Black woman doesn’t have time to cry or emote, because ‘I gotta go to work’ or ‘I gotta take care of this’ or ‘I gotta be the savior for everyone,'” she said.

Economic and cultural factors come into play, too. People who are poor or cut off from systems of care are often forced to rely on their partners or families more, just to get their needs met.

Meanwhile, some non-Western cultures are more collectivist. What Western society might consider to be codependent — like an adult child living with parents — might be considered normal and healthy in those contexts.

Then, there’s this huge cultural force: the portrayal of romantic love.

“Historically, our needs were met by a village of people, right?” said Joy Harden Bradford, a therapist in Georgia.

“Now, romantic love has almost turned into this thing where your partner is expected to meet all your needs,” Bradford said. “When, really, that’s impossible. Like, no one person can be everything for someone else.”

This messaging is all over pop culture, Bradford said.

Consider movies like “Twilight” or “A Star is Born.” People swooned over these films — they were presented as romantic ideals. Yet both featured toxic, codependent relationships.

Can you call it love if it’s codependent?

To be fair, it’s not just culture that’s setting us up for codependency. It’s our brain chemicals, too. That roller-coaster fueled by dopamine, serotonin, and butterflies … it feels so good.

And that’s why it can be hard to suss out codependency early on in a relationship. A few therapists told me that they don’t even bother looking for codependency in the first year or so of a relationship, because it looks like the initial stages of falling in love and wanting to merge hard with another person.

So, how can you tell a codependent relationship apart from a healthy relationship?

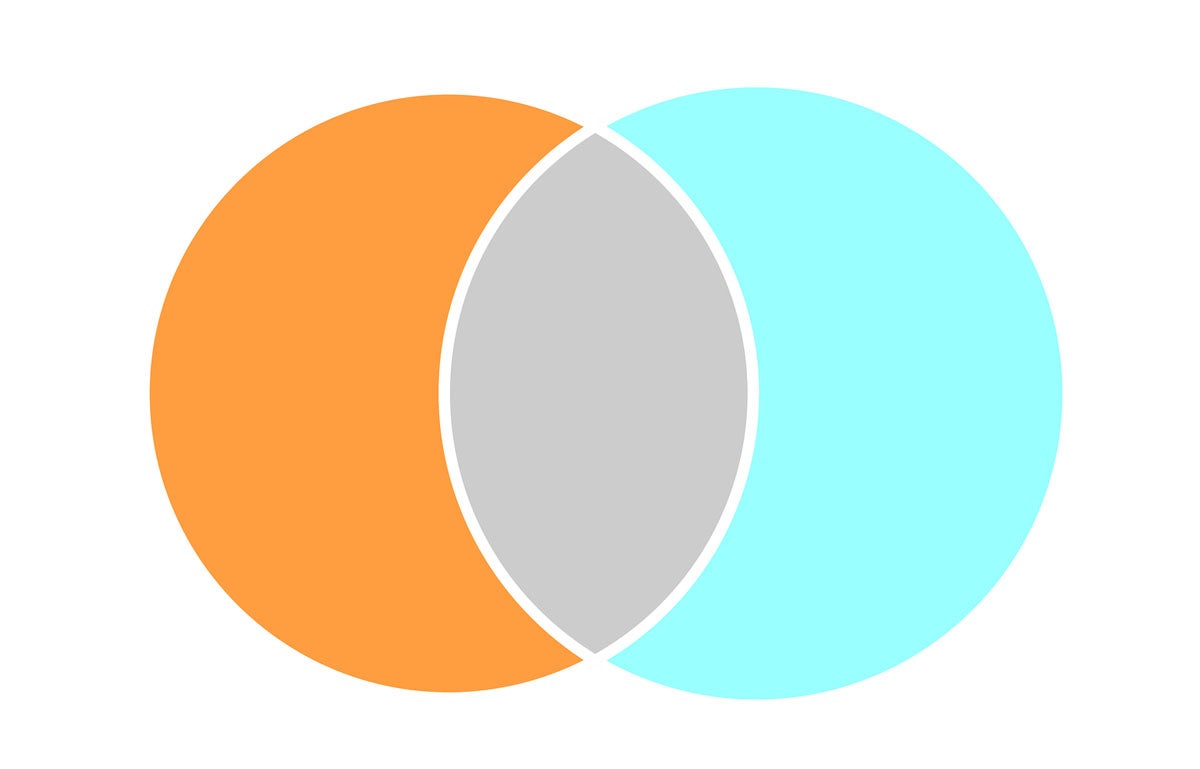

Shawn Burn, the psychologist in California, said that, over time, a healthy relationship should settle into interdependence, rather than codependence.

Think of it like a Venn diagram: two circles, with a bit of overlap, or enmeshment. That overlap is good. You want there to be mutual caretaking and sharing within the relationship.

But there’s also a significant part of each circle that’s independent, or differentiated. Meaning the partners still have their own lives — their unique interests, relationships, and activities.

“There’s autonomy, yet connectedness,” Burn said.

Put another way, healthy love should make each person’s life bigger. But in a codependent relationship, lives can shrink down to just what’s shared in the relationship. Partners become highly enmeshed — even though, at first, they were likely attracted to each other’s individuality.

You might start out loving your partner’s independent hobbies and beliefs, said Chloe Cook, a couples therapist in Georgia. But over time, you both “stop doing the things that you did when you were single.” And in lieu of those things, you start depending on your partner to build your self-esteem.

Research attempts

So codependency can result from trauma, cultural conditioning, love hormones, or a complicated mix of factors.

Rather than pinning down the exact roots of codependency, some researchers have tried to distill it down to its core characteristics or symptoms.

In the 1990s, Lynda Spann, a couples therapist in Colorado, helped develop a codependency screening tool. The Spann-Fischer Codependency Scale asks people to rate themselves on a series of statements, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.”

Based on her research, Spann concluded that codependency boils down to three elements: an extreme focus outside of the self; a lack of openly expressing one’s feelings; and an attempt to derive purpose and meaning through relationships with others, rather than through one’s own self.

Ingrid Bacon is another mental health researcher, based in London, who’s tried to get to the crux of codependency. After scouring the literature, she felt there wasn’t much research exploring the lived experience of codependency from the codependent’s perspective.

She decided to do deep, qualitative interviews with people attending support groups for codependency. As part of those interviews, she asked people to bring in visual representations of how they experience codependency.

One participant came with a picture of a quilt she’d made in childhood. Bacon recalled her saying, “I have a fragmented sense of self. I feel that my sense of self is in bits and pieces.” Recovering from codependency, to that participant, meant sewing the pieces together to construct a more cohesive self.

Another person brought in an image of a chameleon. That person told Bacon, “I’m always modifying myself, like a chameleon. I’m adapting myself to environments, to relationships, to situations where I lose a sense of who I am … and I over-adapt, becoming what is expected of me.”

Bacon’s research led her to define the core characteristic of codependency as a lack of identity, or a low sense of self, which leads people to live between emotional extremes.

Homework for codependents

So, if you think you’re codependent, what can you do?

First, know that codependency is common. It probably exists to varying degrees in every relationship, said Keesha Sullivan, a therapist in Florida.

For Sullivan, getting over codependency is about getting over automatic programming. Codependency happens like an instinct. It “will always be enacted until a different way is learned,” she said.

That’s why people who’ve struggled with codependency for a long time find themselves in the same cycles again and again. To fight it, you have to make it conscious. You can try fortifying yourself, by journaling about how codependency interferes with your goals or your health.

Because codependent people often suppress their emotions, it can also be helpful to practice noticing your feelings, said Misty Hook, the therapist in Texas. “Stop at various times during the day and just check in,” she said. “How am I feeling? Am I anxious? Am I happy? Am I mad?”

The next time someone asks what you want for dinner, if you have a habit of automatically saying, “I don’t care, what do you want?” stop and check in with yourself. What do you actually want? And try naming it.

Of course, one word kept coming up again and again: Boundaries.

Boundaries can be tricky, said Dedeker Winston, a relationship coach and cohost of the “Multiamory” podcast, which explores all types of romantic relationships. The most important part about boundaries is that they are “rules or limits you have put on your own behavior that protect you,” Winston said.

In other words, you’re not using boundaries to change anyone else’s behaviors. Your boundaries are meant to protect you, not to be used as a weapon against others.

Take some time to reflect on your boundaries and come up with plans for enforcing them. If your boundary is violated, you might decide to remove yourself from a conversation, change the way you engage with a person, or even break up with someone.

In any case, it does require “strength of will to apply it to your own behavior,” Winston said.

Knowing your feelings and boundaries leads to more intimate communication between partners, said Darlene Lancer, the author of “Codependency for Dummies.” When you’re talking, try to be radically vulnerable. And when you’re listening, try to be radically curious.

“That’s what keeps relationships alive,” Lancer said. “The aliveness comes from the authenticity.”

To be authentic with others, you first have to be authentic with yourself. Which means you have to know yourself, value yourself, and express yourself — even if that might generate conflict or discomfort.

“When you please and you try to adapt, this gap between your real self and who you want to present to the world grows wider and wider,” Lancer said. “Imagine Pinocchio, growing a nose every time he lies.”

“And when you do the opposite — when you’re authentic, even when it’s uncomfortable — you grow your real self,” she said. “It ignites all your inner power.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.