The Supreme Court deals a new blow to voting rights, upholding Arizona restrictions

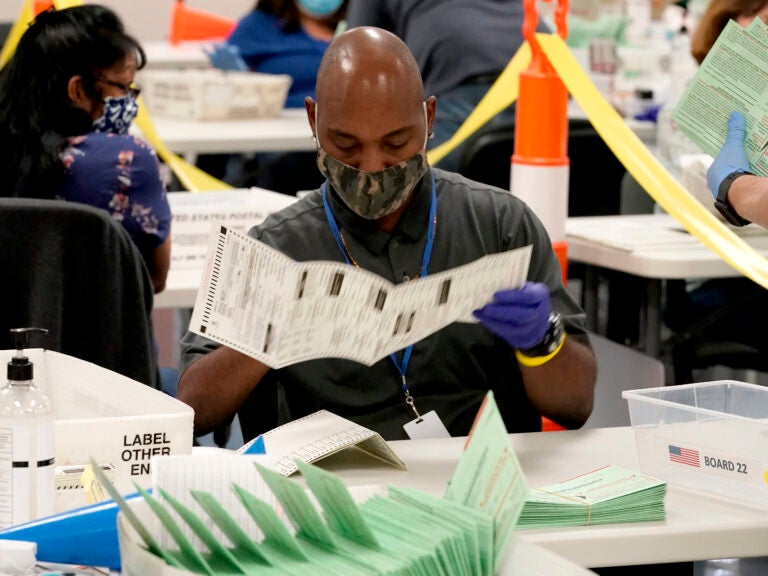

Election workers sort ballots at the Maricopa County Recorder's Office in Phoenix. Mail-in ballots in Arizona are already being counted. (Matt York/AP Photo)

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday narrowed the only remaining section of 1965 Voting Rights Act, rendering the landmark civil rights law close to a dead letter.

Arizona had banned so-called “ballot harvesting” as well as a policy that threw out an entire ballot if it was cast in the wrong precinct.

The 6-3 vote was along ideological lines. Justice Samuel Alito write the majority opinion for the court’s conservatives. Justice Elena Kagan and the court’s two other liberals dissented.

The “Court declines in these cases to announce a test to govern all VRA [Section 2] challenges to rules that specify the time, place, or manner for casting ballots,” Alito wrote. “It is sufficient for present purposes to identify certain guideposts that lead to the Court’s decision in these cases.”

The landmark law, widely hailed as the most effective piece of civil rights legislation in the nation’s history, was reauthorized five times after its original passage in 1965, but for all practical purposes, all that is left of it now is the section of the law banning vote dilution in redistricting, based on race.

Eight years ago, the court by a 5-to-4 majority gutted the law’s key provision, which until then required state and local governments with a history of racial discrimination in voting to get approval from the U.S. Justice Department for any changes in voting procedures.

When that provision was struck down by the court in 2013, the only protections for voting rights that remained in the law were in Section 2.

Though Section 2 has largely been used to prevent minority vote dilution in redistricting, importantly, it does bar voting procedures that “result in a denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” So the Arizona case was viewed as particularly important because it was the first time the court dealt with a claim of vote denial under Section 2 and how to evaluate it.

“This Court has no right to remake Section 2,” Kagan wrote in her dissent. “Maybe some think that vote suppression is a relic of history—and so the need for a potent Section 2 has come and gone. … But Congress gets to make that call. Because it has not done so, this Court’s duty is to apply the law as it is written. The law that confronted one of this country’s most enduring wrongs; pledged to give every American, of every race, an equal chance to participate in our democracy; and now stands as the crucial tool to achieve that goal. That law, of all laws, deserves the sweep and power Congress gave it. That law, of all laws, should not be diminished by this Court.”

Specifically at issue were two laws. One barred the counting of provisional ballots cast in the wrong precinct. The other barred the collection of absentee ballots by anyone other than a family member or caregiver.

Arizona Republicans and the Republican National Committee argued that both were needed to prevent fraud. But the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that there was no record of fraud, and that there was evidence that these two provisions ended up denying many minorities the right to vote. The appeals court noted, for instance, that ballot collectors were needed in some large, rural and remote parts of the state. It pointed, for instance to the Navajo Nation, an area the size West Virginia, where there are few post offices or postal routes, and where people without cars often have no way to send their ballots without collectors picking them up.

The high court, however, rejected the lower court findings.

Arizona, of course, has been ground zero for Donald Trump’s claims that the election was stolen, and a Trump-inspired audit has been taking place (took place) in the state in May. The attempt to undo the certification of the election results was widely discredited, even by some Republican officials, and was meaningless because the state’s electoral voter were long ago certified for Joe Biden.

But the court’s decision could play an important role in next year’s mid-term elections, and elections thereafter.

Many Republican dominated states have passed laws far more problematic than the two at stake in Arizona. Indeed, the two laws at the center of Thursday’s case are not unusual. Other states have enacted limits on absentee ballot collectors, especially when fraudulent practices have been uncovered. Although the Ninth Circuit found no evidence of fraud in the Arizona election system, problems with absentee ballot collection systems have occurred elsewhere. Perhaps the most prominent example came in 2018 in North Carolina when a Republican vote collection and tampering scandal resulted in a new congressional election being ordered for one district.

In the wake of Trump’s false allegations that Democrats stole the 2020 election, many states, particularly those dominated by Republicans, have sought to change voting laws in a way that critics say is aimed at curtailing the right to vote, particularly among minorities. Last month, the Brennan Center for Justice reported that 22 new voting laws had been enacted and 389 proposed in 48 states just since the 2020 election.

The U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill, H.R.1, that would have set federal standards and overridden voter suppression provisions across the country, but in the Senate opponents blocked consideration of the bill.

The laws that the court ruled on Thursday are not themselves unique, and some Democrats consequently thought that challenging them risked a decision that would make it harder to challenge other restrictions in the future. But former Democratic Party chairman Tom Perez maintained that the situation in Arizona was different because of the huge rural areas without postal service in the state.

At the same time, GOP lawyers defending the laws candidly admitted during the oral argument in the case, that the Republican legislature’s motive in enacting the Arizona voting restrictions was less anti-fraud and more political.

Not having such restrictions “puts us at a competitive disadvantage,” said lawyer Michael Carvin, on behalf of the GOP. ” Politics is a zero sum game, and every law they get through an unlawful interpretations of Section 2 hurts us.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))