Most prisoners can’t vote, but they’re still counted in voting districts

Updated September 26, 2021 at 7:01 AM ET

Prisoners are among the country’s least powerful people. But every 10 years, where they’re counted in census numbers can shift political power in the United States.

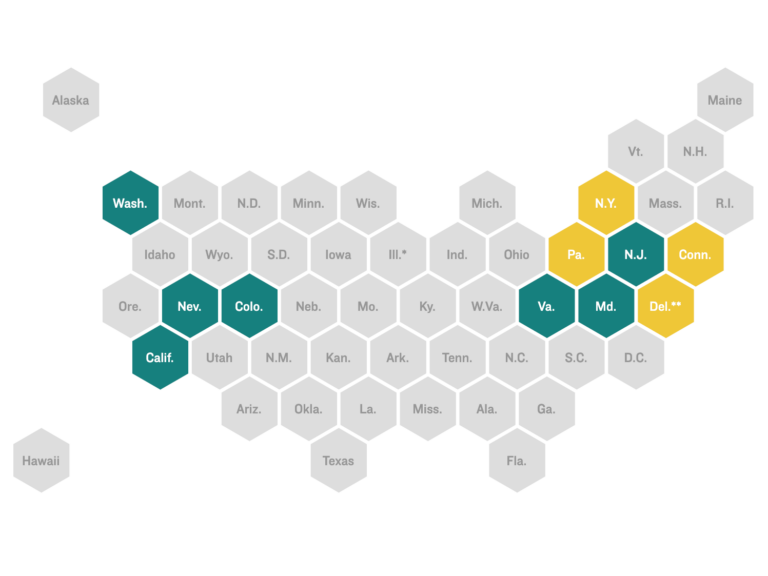

And as mapmakers turn last year’s census tallies of incarcerated people and other U.S. residents into the next decade’s voting districts, 11 states are trying to block what critics call “prison gerrymandering.”

That little-known practice involves determining the areas elected officials represent with census numbers that count prisoners as residents of where they are incarcerated. With those tallies, some redistricting officials have created local voting districts filled mostly with people who are locked behind bars and, in most states, cannot vote.

There’s a growing movement, though, to modify those census numbers before they’re used for redistricting — by reallocating counts of incarcerated people to where they last lived before they were imprisoned.

The 11 states with laws or redistricting commission resolutions for reassigning prisoner counts in this redistricting cycle each have their own way of modifying the census tallies. Some local governments have also developed methods to avoid forming districts made up primarily of incarcerated people. (Illinois has a new state law that’s expected to go into effect in time for redistricting after the 2030 census, and Colorado’s Independent Congressional Redistricting Commission decided last month to not reallocate prisoner counts for redrawing congressional maps despite a requirement under state law, which some consider unenforceable in light of a recent Colorado Supreme Court ruling.)

Last week, Pennsylvania’s Legislative Reapportionment Commission ultimately decided that when redrawing state legislative districts, people held in state prisons and serving minimum sentences that end on or before the next Census Day — April 1, 2030 — are to be counted at their last known addresses if they were living in the state immediately before they were incarcerated.

This kind of change, first modeled a decade ago by Maryland and New York, is expected to move political power away from prison towns. Many are rural, predominantly white areas that, for decades, have seen their census numbers boosted by the disproportionately Black and Latinx people who are incarcerated within their borders.

Are prisons the “usual residence” of all prisoners?

For the census, the federal government has counted incarcerated people where they’re locked up, including jails, since the first national tally in 1790. That’s when federal law specified that people should be counted at their “usual place of abode,” which the Census Bureau has interpreted to mean where they live and sleep most of the time.

Before the 2020 count, however, the bureau asked the public for feedback on its residence criteria. More than 99% of the close to 78,000 public comments about incarcerated people called for prisoners to be tallied in their home communities.

“They send me to a rural area, they count me in a rural area, and they get the benefit of what this body is worth,” says Dorsey Nunn, one of the commenters who serves on the Formerly Incarcerated, Convicted People and Families Movement’s steering committee.

Nunn, who is also the executive director of Legal Services for Prisoners with Children based in Oakland, Calif., sees parallels to how the Constitution originally required the census to count an enslaved person as three-fifths of a free person.

“I find it obnoxious, repulsive and objectionable that they’re going to count me like a slave while they’re holding me like one in some institution,” Nunn adds.

Still, the bureau concluded in 2018 that it would continue its long-standing policy, noting that counting prisoners anywhere other than where they’re held “would be less consistent with the concept of usual residence, since the majority of people in prisons live and sleep most of the time at the prison.”

Some formerly incarcerated people are concerned prisoners’ interests don’t seem to matter

Advocates against “prison gerrymandering” question whether it’s fair to consider the prison where incarcerated people happen to be held on Census Day to be their residence. Some prisoners serve sentences shorter than six months, and those with longer sentences are often transferred to other locations.

Critics of the bureau’s policy also point to the implications on political representation in a country that locks up more people than any other. While the numbers have fallen in recent years, the U.S. remains the country with the world’s highest incarceration rate, according to World Prison Brief by the University of London’s Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research.

Abd’Allah Lateef, one of three formerly incarcerated Black men from Philadelphia who joined the NAACP in a lawsuit last year that tried to force Pennsylvania to change where prisoners are counted for redistricting, recalls feeling “displaced and isolated” while serving time and trying to reach his elected officials.

“Your interests didn’t matter to anyone in policy,” says Lateef, who on Census Day in 2010, was held at a state prison in Pennsylvania’s Greene County, more than 300 miles away from his hometown. “The only thing that mattered was that you were representative of a number.”

Prison towns have reaped political power for decades

The rise in the country’s incarcerated population since the 1970s has brought political power to many areas with prisons, especially in states where the population numbers the Census Bureau produces are used as is to redraw voting districts.

Calls to change where prisoners are counted for the census have drawn pushback from Republicans, including the late GOP redistricting strategist Thomas Hofeller who once wrote that the effort is “being encouraged by Democratic or Liberal organizations and could involve the Census Bureau in yet another political conflict.”

Last year, Virginia’s Democrat-controlled General Assembly passed a state law that requires 2020 census numbers to be modified before they’re used for redistricting. For the redrawing of congressional, state legislative and local voting districts in Virginia, prisoners with last known addresses in the state are to be counted there instead of where they’re incarcerated.

But in August, Republican State Sen. Travis Hackworth filed a lawsuit that challenged how this new redistricting rule was put in place.

The case, which was dismissed last week on procedural grounds, argued that reallocating prisoner counts will ultimately “reduce the voting power and representation of permanent residents” of districts that typically have “greater Republican voting strength.” Those residents, the suit also contended, “often expend substantial local resources to support their local correctional facilities.”

Opponents of “prison gerrymandering” are focused on the political power of Black and Latino communities

Local governments do sometimes receive federal money that is distributed based on funding formulas that factor in census numbers, which, for prison towns, include the counts of incarcerated people.

But for Robert Holbrook — the executive director of the Abolitionist Law Center who joined Lateef in the Pennsylvania lawsuit, which was dismissed on procedural grounds in January — reallocating prisoner counts to their home communities is “not about the money.”

“Mass incarceration disproportionately impacts Black and brown communities. Therefore, when you have prisoners from these communities incarcerated in prisons in rural, white districts, it is depriving political representation to these communities,” says Holbrook, who was counted for the 2010 census as a resident of Pennsylvania’s State Correctional Institution at Greene, where Lateef was also held. “And when you’re dealing with the state legislature, all resources and all funding flow from your representation in that state legislature.”

“When we start talking about voting rights and how that has impacted especially the Black and brown communities, this is a part of that,” says Corrie Betts, chair of criminal justice for the NAACP’s state conference in Connecticut, another state with redistricting rules for reallocating prisoner counts.

Pinpointing where prisoners used to live is complicated

Counting prisoners at their last known addresses is not as easy as it may sound.

Last month, the Census Bureau released counts of people in correctional facilities at the same time it put out new redistricting data. But states with new redistricting rules still have to sort through prison records.

“You might have an address for somebody, but it’s missing the ZIP code,” explains Aleks Kajstura, who is the legal director at the Prison Policy Initiative, the leading advocacy group for counting incarcerated people in their home communities. “Once you’re trying to map thousands of addresses, all of a sudden missing a few ZIP codes kind of starts to add up.”

It’s a challenge that Karin Mac Donald, director of California’s redistricting database, started trying to prepare for about seven years ago after learning that her state would require the counts of people held in state prisons whose last known residences are in California to be reallocated before voting maps are withdrawn.

“In many states, redistricting data are built pretty much at the very last possibility because there’s no funding available to do it over time,” says Mac Donald, who worked with the state’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to obtain records. “For us, we knew this was coming.”

New privacy protections may make the process even messier

Mac Donald, however, has been concerned about how the new privacy protections the Census Bureau applied to the 2020 census redistricting data could throw another “wrinkle” into the process.

Because those protections intentionally skew data at the census block level in order to keep people anonymous, the number of prisoners, as well as their racial and ethnic demographics, that the bureau reports for a block may not match with the data in prison records.

How state and local redistricting officials deal with that uncertainty when redrawing voting maps could have implications on how the voting rights of people of color can be protected, according to Doug Spencer, an associate professor at the University of Colorado Law School who is an expert on Voting Rights Act lawsuits.

“It will be more difficult to bring these cases,” says Spencer, who is currently running the website All About Redistricting, which is tracking the redrawing of political maps across the country. “What that requires then is voting rights experts and redistricting commissions to be more transparent about their choices.”

Advocates are looking ahead to potential changes by 2030

Despite these complications, advocates of changing where prisoners are counted say they’re committed to seeing more change in time for the next round of map drawing, after the 2030 census.

By then, more states could put in place new redistricting rules — and the Census Bureau could adopt a different policy for where it counts prisoners, which would lessen the burden on states having to modify redistricting data themselves.

“We’re not going to go away,” says Terrance Lewis of Philadelphia, one of the formerly incarcerated men who filed the Pennsylvania lawsuit and who was ultimately exonerated of a crime he did not commit. “I believe, in time, that scheme is going to go down.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))