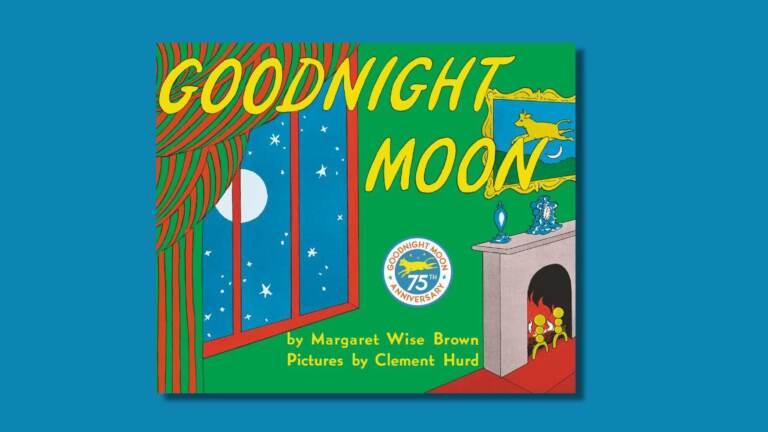

Goodnight Moon has comforted kids at bedtime for 75 years

(Meghan Collins Sullivan/NPR)

Without mystery, hero, handsome prince or fairy godmother — Goodnight Moon has now lulled millions of children to sleep, in more than two dozen languages, for 75 years.

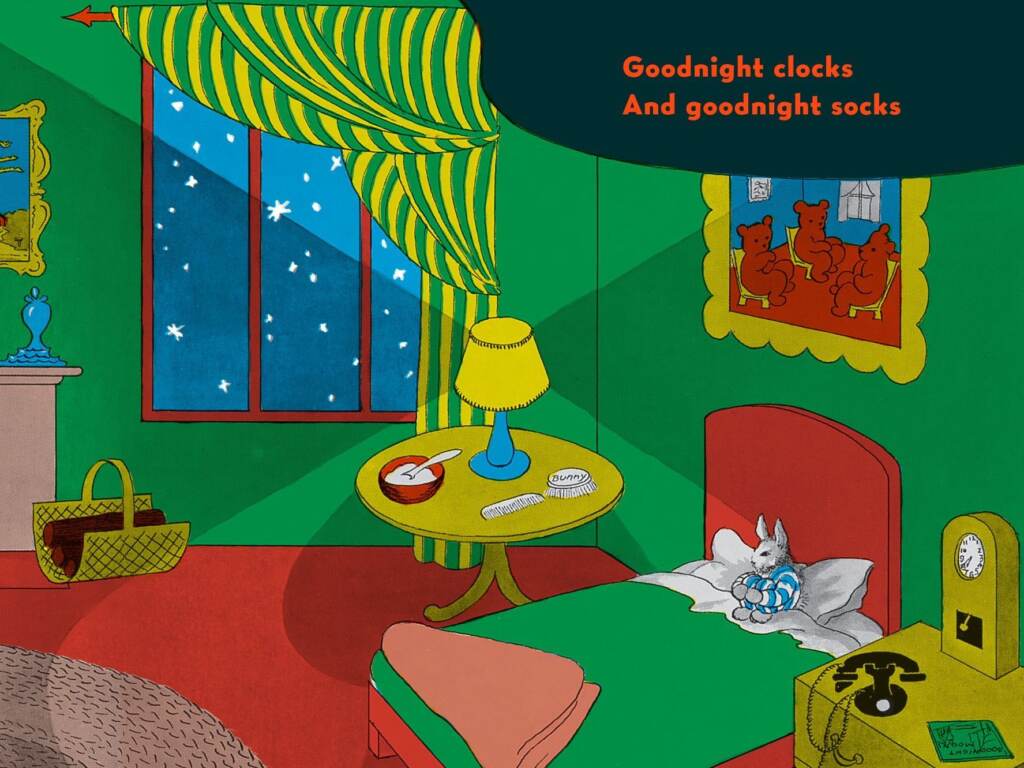

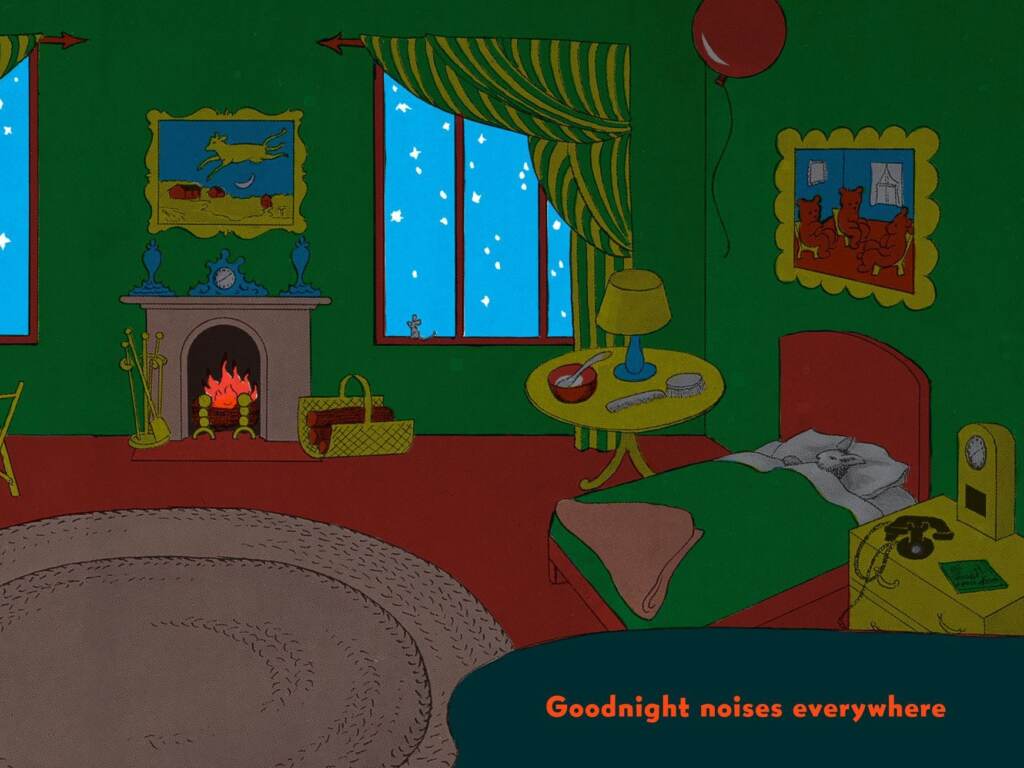

Written by Margaret Wise Brown, with illustrations by Clement Hurd, the picture book, which has sold more than 40 million copies since its publication on Sept. 3, 1947, wins its readers with a soothing series of goodnights to the everyday objects in “the great green room” before bedtime.

“It mirrors what’s happening for the child, but it also gives them a feeling of some other world, something else that’s sort of a larger, more peaceful world,” says Thacher Hurd, Clement’s son and himself a children’s book author and illustrator.

“‘Good night stars and good night air. Good night noises everywhere.’ It’s very expansive. You don’t even think about it, but it is extremely sort of open and wide and a big feeling to it,” reflects Hurd.

Goodnight Moon has been adapted for stage and screen, been featured on The Simpsons, parodied, and given a special reading by LeVar Burton to Neil deGrasse Tyson. To celebrate its 75th anniversary, HarperCollins is publishing a special slipcase edition with a new foreword by Thacher Hurd.

But the now iconic picture book was by no means an overnight sensation. Hard to believe — but in 1947 this innocent bedtime ritual was considered revolutionary.

Fairy tales versus the here-and-now

Once upon a time, librarians set the standard for what books children should read. For decades, they believed classic fairy tales and fantasy were best for young minds, says children’s book historian Leonard Marcus. They favored stories, he explains, “that transported children out of the everyday world and enriched and cultivated their imagination.”

By contrast, Brown brought children into a world they might know.

“Goodnight Moon was one of the first books for young children that focused on the everyday and recognized its value and significance for young children,” says Marcus, author of Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon.

In 1935, Brown began a long association with the progressive Bank Street school in New York City. Founded by educator and writer Lucy Sprague Mitchell, Bank Street brought together psychologists, pediatricians, sociologists, and student teachers to explore how children learn. They collected data by observing and talking directly to the experts: the children themselves. Their findings are neatly summed up in the title of Mitchell’s Here And Now Story Book.

Marcus says Bank Street practitioners learned that children, “want to know about the world they’re in at the moment, starting with their own room and their own surroundings and their own street. The noises they hear, the airplanes that go overhead, the trains and cars that go by, they thought all those everyday things were wonderful from a from a young child’s perspective.”

The udder problem

Goodnight Moon had its own kind of “here-and-now” spirit. But for a children’s book to be commercially successful in 1947, it needed the approval of the New York Public Library, namely its influential children’s librarian Anne Carroll Moore.

Moore had an aversion to the progressives at Bank Street, something Goodnight Moon‘s editor at Harper’s, Ursula Nordstrom, knew first-hand. In 1945, Moore tried to prevent another book Nordstrom edited, E.B. White’s Stuart Little, from being published. Moore was apparently disturbed at the thought of a mouse being born to a human.

Nordstrom, says Marcus, understood that Moore and other librarians “were very squeamish about bodily parts and physicality in general.” So she told illustrator Clement Hurd to make small tweaks to a couple of the items in his vibrant and detailed “great green room.”

In an early version of Hurd’s artwork, the mouse was on the little bunny’s bed and the cow jumping over the moon in the picture on the wall was anatomically correct with an udder. Take the mouse off the bed and remove the udder from the cow, Nordstrom advised. “She was on the alert,” says Marcus. “She didn’t want to deep six a book based on one or two details in the pictures.”

When Goodnight Moon was published in 1947, reviews were generally positive. The Christian Science Monitor wrote, “in these days of hurry and strain, a book for little children which creates an atmosphere of peace and calm is something for which to be thankful.” Kirkus Reviews called it a “really fresh idea.”

But, despite Nordstrom’s efforts, Moore was not impressed. The New York Public Library not only excluded Goodnight Moon from its recommended children’s book list, it didn’t even acquire it for the NYPL system.

“What they didn’t understand was, [Brown] went straight to the child and that sort of basic human need,” says Jean McGinley, vice president and associate publisher for HarperCollins’ Children’s Books. McGinley calls Brown a “trailblazer” who “broke a formula” and incorporated “social emotional learning…before anybody else.”

Margaret Wise Brown was something of a glamourous, wild-child: a spirited, creative and experimental writer known for wearing furs and driving a convertible. She loved rabbits and kept them as pets. The Runaway Bunny is another Brown/Hurd collaboration. But she was also active in the sport of “beagling” in which runners race through the woods after beagles chasing down hares or rabbits — and not to kiss them goodnight. “She was not like a sweet, cute children’s book writer,” remarks Thacher Hurd wryly.

“I don’t especially like children”

Commenting on the possible contradiction between creating cuddly bunny characters and hunting them for sport, Brown told Life magazine, “Well I don’t especially like children, either,” she continued, “at least not as a group. I won’t let anyone get away with anything just because he is little.”

But Brown expressed that she was very much in touch with her inner child. She once said that, to be a children’s writer “one has to love not children but what children love.” And Brown did understand and give children what they wanted. In addition to writing more than 100 stories for them, she championed and edited other children’s book writers and illustrators. She introduced the board book after observing small children chew on pages, and picture books with fur and bells and other tactile sensations.

“A book can make a child laugh or feel clear-and-happy-headed as he follows a simple rhythm to its logical end,” Brown once said. “It can jog him with the unexpected and comfort him with the familiar, lift him for a few minutes from his own problems of shoelaces that won’t tie and busy parents and mysterious clock-time, into the world of a bug or a bear or a bee or a boy living in the timeless world of story. If I’ve been lucky, I hope I have written a book simple enough to come near to that timeless world.”

Margaret Wise Brown never lived to see Goodnight Moon‘s colossal success. In 1952, on a trip to Paris, she died suddenly from an embolism following an operation. She was 42 years old. Twenty years later, the New York Public Library acquired Goodnight Moon and eventually named it one of the “Books of the Century.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))