A fishing line encircles Manhattan, protecting sanctity of Sabbath

This fishing line, barely visible between Manhattan buildings, is an eruv, used by observant Jews to create a symbolic domestic perimeter for the Sabbath. (William W. Ward/Creative Commons)

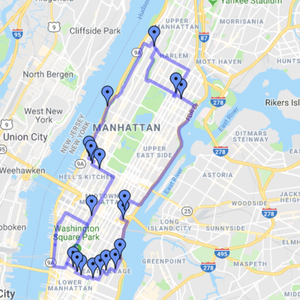

A clear fishing wire is tied around the island of Manhattan. It’s attached to posts around the perimeter of the city, from 1st street to 126th. This string is part of an eruv, a Jewish symbolic enclosure. Most people walking on the streets on Manhattan do not notice it at all. But many observant Jews in Manhattan rely on this string in order to leave the house on Sabbath.

The concept of the eruv was first established almost two thousand years ago, to allow Jews to more realistically follow the laws of Sabbath rest, particularly one — no carrying on the Sabbath.

According to the laws of Sabbath rest, nothing can be carried from the domestic zone into the public zone on Saturday. That means no carrying house keys or a wallet. It also means no pushing a baby stroller. For parents of young children, no carrying would mean not leaving the house on Saturday.

The eruv symbolically extends the domestic zone into the public zone, permitting activities within it that would normally be forbidden to observant Jews on the Sabbath.

Imagine a whole day cooped up in a Manhattan apartment with a toddler and no electricity. “You might be going a little bonkers because your apartment is so small,” says Dina Mann. “But you don’t realize it’s so small until you’re stuck in there and you can’t go anywhere.”

Mann lives on Manhattan’s Upper West Side with her husband and two young children. They observe Sabbath rest, including refraining from carrying. She says, “If you’re really really really strict, then you would not even pick up your child.”

Mann and many others rely on the eruv every Saturday to leave the apartment with their children. Luckily, Manhattan’s eruv has never been down. Rabbi Mintz, co-president of the Manhattan Eruv says, “It has never been down for a Sabbath. Never. We always save it at the last minute.” Mintz noted that the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade is always a particularly trying time.

More than two hundred cities around the world are partially encircled by an eruv. Manhattan’s certainly isn’t the largest, but according to Rabbi Mintz, it’s the most expensive eruv in the world. It costs between $125,000 and $150,000 a year to maintain. Rabbi Mintz helps raise the funds every year from synagogues and private donations.

Every Thursday before dawn, a rabbi drives the perimeter checking to see if wind or a fallen branch has broken the line. There are usually a few breaks so a construction company is called and the rabbi gets in a cherry picker with fishing line in hand to repair the eruv. That’s the part that costs so much.

As it turns out, resting on the Sabbath takes a lot of preparation. Dina Mann says the eruv does more than just help her enjoy a Saturday walk in the Central Park, it lets her enjoy the Sabbath. “There’a a warmth in the house the minute you light the candles because you’re rushing, rushing, rushing, making sure all the lights are on, making sure the candles are in there, making sure all the food is cooked … Then you just light the candles and just like let go of everything.”

Most important of all, the eruv allows her to rest from worry.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))