A conspiracy video teaches kids a lesson about fake news

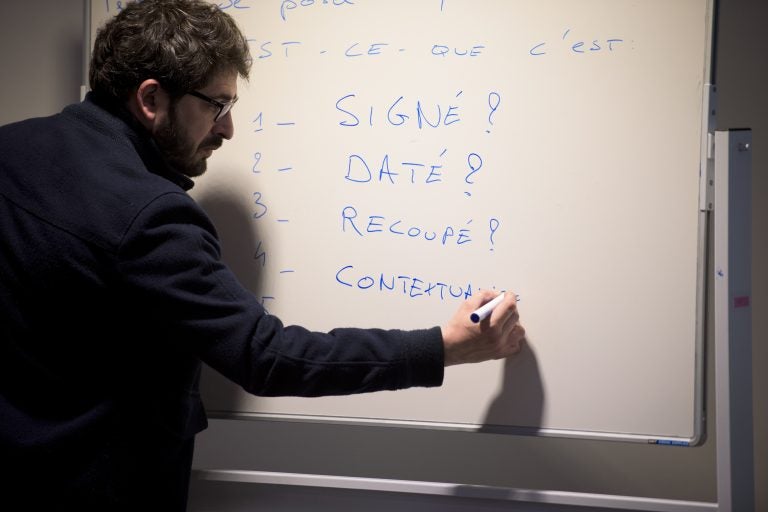

Investigative journalist Thomas Huchon writes five questions that can be used to evaluate the veracity of a news story. (Pete Kiehart for NPR)

Our Take A Number series is exploring problems around the world through the lens of a single number. Today’s number is 81, which is how many French schools a journalist visited to teach kids about disinformation on the Internet.

As the bell rings, students file into class at Maxence Van der Meersch middle school. This morning the kids have a visitor — investigative journalist Thomas Huchon.

Without telling them the topic of his visit, Huchon says he’s going to show them a mini-documentary.

The video claims that the CIA spread the AIDS virus in Cuba, and says that was the real reason behind the decades-long U.S. embargo. It was only lifted, the narrator says, so American and French pharmaceutical companies could cash in on an AIDS vaccine developed by Cuban doctors.

The students don’t yet know it, but Huchon and his colleagues at video news network Spicee created the video themselves, as part of an experiment after the French terrorist attacks in 2015. They noticed how conspiracy theories against the official version of the attacks were spreading on the Internet, and they wanted to do their own experiment.

“So we created a fake story,” says Huchon. “We put it on the Web, and what we expected to happen happened: Lots of conspiracy theorist websites picked up on this information and spread it without any kind of verification.”

Huchon says that before they removed it, their video had 10,000 hits on YouTube and thousands of shares on Facebook.

Widespread concerns about the inability of many people in France to tell a real news story from a fake one have led this French journalist to visit 81 schools since 2016, on a mission to teach kids about fake news and disinformation.

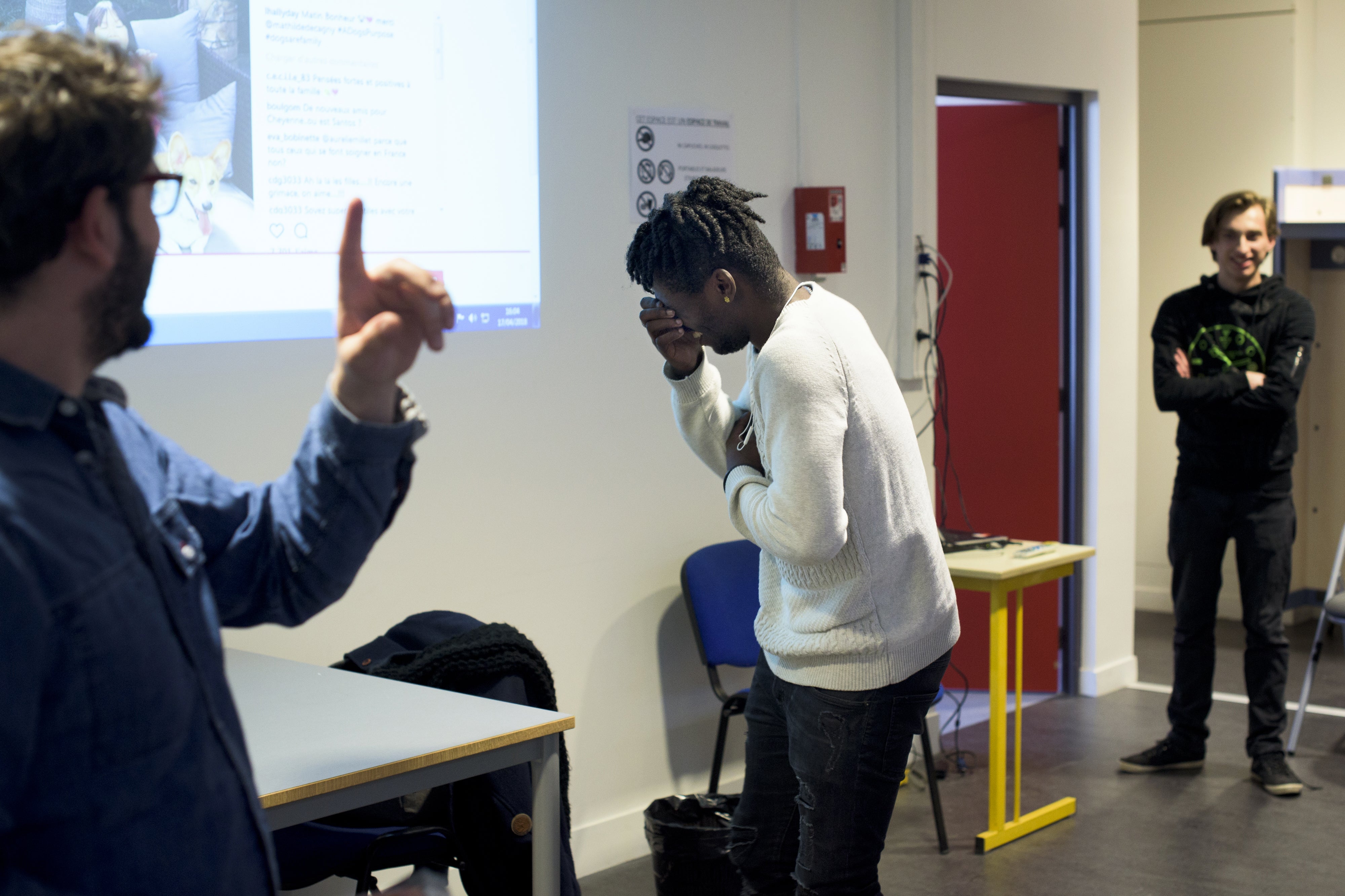

In this classroom, in the seaside town of Le Touquet in northern France, Huchon asks the kids to raise their hands if they believed the documentary.

One girl with her arm in the air says it’s absolutely unconscionable what the United States did. Usually, about a third of the students believe the hoax, Huchon says, because they have no reason to be skeptical of him.

“And we play with this,” he says. “We use this as a trap to make them realize that even when they are in confidence they should not believe de facto. They should have a few reflexes to try and fact-check a little bit more.”

Huchon puts on a second video that tells the class that the first one was a total lie. It also explains how conspiracy theories are made to look credible: menacing music; trigger themes like the CIA and AIDS; highlighted text the viewer doesn’t have time to read; and always some historical facts and truths sprinkled between the many lies.

The kids are shocked. Many feel tricked. So Huchon shows them how they can keep from being fooled again.

First off, he says, they have to check the authenticity of articles, pictures and videos. To do that they must first make sure that the author has put his name and the date on the work. That will help them cross-check the information on other sites. They should also try to go upstream to look for some of the original sources.

Another important element is to verify that the information is not taken out of context. That a picture, for example, does not claim to be taken somewhere it’s not.

They talk about a picture making the rounds of anti-Muslim websites. It shows Muslim women wearing the burqa standing in line for welfare benefits. The face-covering veil is illegal in France. The picture was actually taken in London.

The class also has a long discussion about being careful with pictures and personal information on the Internet. Huchon explains to the kids how their personal information — even such minor things as “likes” on Facebook — is used by advertisers to target them. American voters were targeted in this way, he tells them, and it may have altered the 2016 presidential election.

After the two-hour session, 13-year-old Sharon Victor Caron says Huchon has changed the way she sees the Web.

“I’m going to be so much more careful now and not be fooled like so many people are,” she says. “And I definitely will think before sharing something that could be false.”

Huchon says a steady stream of teachers contacts him to come into their classes. He says it’s not easy for the teachers because they are dealing with a generation that operates with new codes and has new ways of getting information. He says presenting alternate facts is not the way to combat conspiracy theories.

“When, for example, a pupil is going to put forward a conspiracy story about World War II and say that, for example, the gas chambers didn’t exist, the teacher will be completely taken aback,” says Huchon, and the teacher will often try to counter this discourse with facts.

Huchon says facts against facts is a fight you can never win. And conspiracy theories strip a teacher’s authority.

“The best way to fight this kind of fake news discourse is not to give counterarguments,” he says, “but to try to check the validity of the other person’s argument.”

President Emmanuel Macron has proposed enacting a law to fight fake news during French elections. Huchon says that won’t work. He says the only way to win is to teach young people how to think critically.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))