WHYY sent a reporter to listen to communities impacted by gun violence. Here’s what we heard

WHYY’s first-ever gun violence prevention reporter took a two-month listening tour in Philly’s hardest-hit communities. Here’s what she learned.

WHYY's Sammy Caiola talks with Tamika Borum at Tynirah's Community Welcome Garden in Gray's Ferry. The garden was named in honor of Borum's daughter, who was shot to death in 2014 at the age of 3 outside her home. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Stephen Flemming and Roxanne Wilson linger at 67th and Greenway avenues in Southwest Philadelphia, chatting the way two neighbors might while asking about the kids or discussing the weather. Except, they aren’t looking at each other.

Instead, their gazes are fixed across the intersection, where two 32-year-old men shot and killed each other the night before, leaving 13 spent shell casings on the street.

“The violence just doesn’t stop,” said Roxanne Wilson, who serves as block captain for the area.

The double homicide was part of a gruesome tally on that Thursday and Friday: 24 shootings across the city of Philadelphia in a 24-hour period.

Since then, Philly’s shooting total has topped 1,000 — including a mass shooting event on South Street that injured 11 and killed three.

Every bullet creates a cluster of victims — friends and parents and grandmothers whose lives change in an instant. Trauma ripples out from there, creating a parallel crisis for those who haven’t yet lost someone to gunfire but fear it on a daily basis.

Only 44% of Philadelphians feel safe in their neighborhoods at night, according to an April Pew Charitable Trusts report. And 65% reported hearing gunshots near their homes in the past 12 months.

Flemming, who teaches history at Martin Luther King High School, says gun violence has become “a way of life” in the city, to the point where some people are numb to it.

He isn’t, though. He’s had to go to more student funerals than he can count on one hand.

“It still hurts when it happens.”

Wilson is worried about her own son.

“[He] go out at night, I pray,” she said. “I pray he come back in the house.”

But fear isn’t keeping these neighbors inside. They aren’t hunkering down in their living rooms or fleeing the city. They’re consoling each other.

“It’s cathartic for us to talk about it,” Wilson said.

Across the street, longtime gun violence activist and former hunger striker Jamal Johnson stands alone, his blue eyes meeting the gaze of passing drivers. He holds a sign that reads, “Stop Killing Us” with a photo of a “no guns” logo. Nearly every day, he is somewhere in the city, holding a sign on a different corner to honor the recently slain.

He says the time for Philadelphians to wait around and hope for change is over.

“This should not be tolerated,” Johnson said. “And the fact that people are comfortable coexisting with this violence, I just can’t fathom it. That’s why I’m out here.”

I joined WHYY as the station’s first-ever gun violence prevention reporter in February, and I’ve spent the past three months following Philadelphians like Wilson, Flemming, and Johnson — people who are “taking back the village” and trying to build a kinder, more caring and more peaceful city.

I started with a 60-day “community listening tour” to neighborhoods hardest hit by gun violence: North Philadelphia, Strawberry Mansion, Kensington, Allegheny West, East Falls, Germantown, Nicetown, and West Philadelphia.

This is the story of that tour.

A new way to report

It was an unusual assignment: Spend two months learning about the issue and meeting the people at the center of it, without publishing any stories.

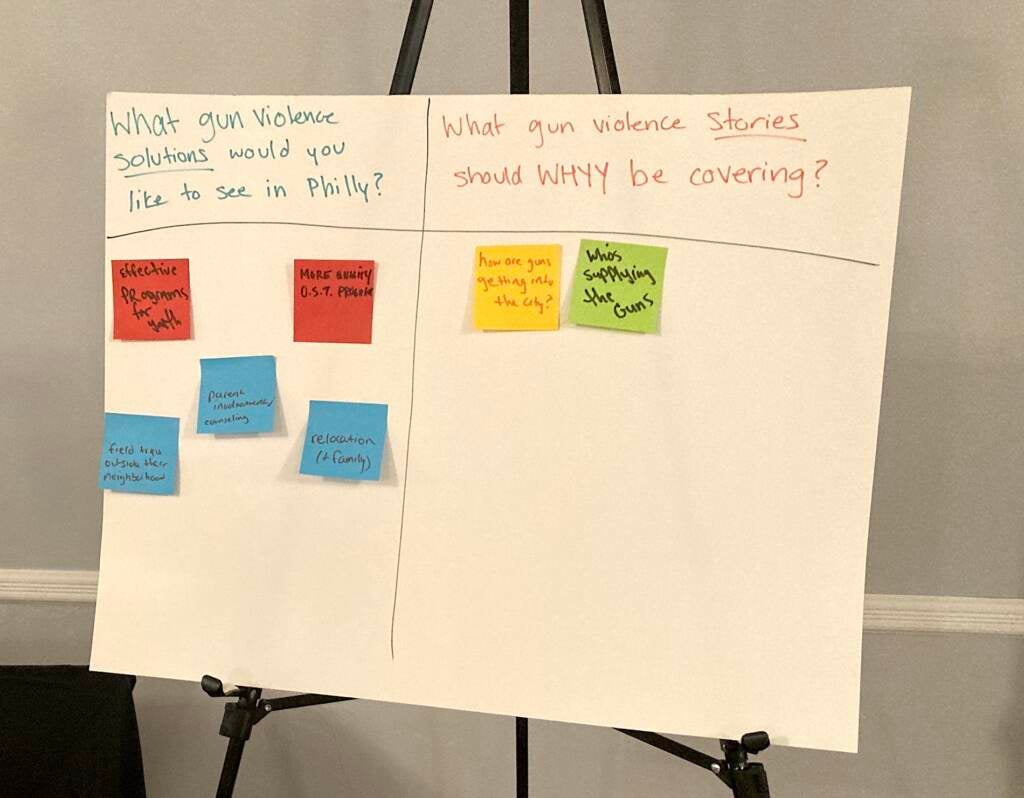

So, I went to Friday night basketball games, neighborhood clean-ups, open mic nights, and corner protests. I listened in on community safety meetings, visited after-school programs, and set up tables at public forums hosted by the city of Philadelphia. I didn’t bring a microphone. I just talked, and listened.

WHYY editors created the Gun Violence Prevention Reporter position earlier this year from a place of frustration. They were disheartened by the way Philadelphia journalists were addressing — or failing to address — a public health crisis that many Black residents consider a more serious threat than COVID-19.

Media outlets often take an episodic approach to firearm injury and death. Reporters rush in when there’s a major incident, putting a mic in front of residents and then leaving to write the story on deadline.

The next time a tragedy strikes, it’s rinse and repeat. Reporters sent to cover these crimes usually don’t know the neighborhood. And they rarely have training on interviewing people experiencing trauma.

There hasn’t been enough attention paid to whether media coverage on gun violence is actually helpful to the people living the crisis. And there’s reason to believe that the way reporters do their jobs is actually damaging to the people they’re covering. Surface-level coverage of shootings can perpetuate harmful stereotypes about victims and perpetrators, and completely fail to address the historic economic and racial factors that contribute to the crisis. By focusing on the problem without highlighting any solutions, news media contributes to the sense of hopelessness that causes many Philadelphians to tune out of the gun violence conversation entirely.

I’m determined to do things differently.

I’m not from Philadelphia. I grew up in New York and I spent most of the last decade in Northern California. I’ve also never lost anyone to gun violence, and I’ve never lived in a place where I felt unsafe.

But not far from my block in West Philadelphia, people are shooting each other on a regular basis. Children are being struck by bullets while playing outside or walking down their streets. Mothers are losing their teenagers. This is not normal, and no one should be OK with it.

The crisis is disproportionately taking Philadelphia’s Black men — who made up about three-quarters of shooting victims and fatalities in 2021. Residents I’ve spoken to are grappling with the long-term impact of the continued loss of fathers and sons, year after year, sometimes referring to this demographic as “endangered.”

Women and children are also being impacted more than they used to be. Nationally, gun violence has surpassed car accidents as the number one cause of injury-related death for children over the age of one, for the first time ever.

So I’m here to learn everything I can about the gun violence crisis from the people bearing the brunt of it, in hopes of shifting the narrative in a way that leads to solutions. I do so knowing that:

- It takes time and energy for people to educate me

- Talking to media is challenging and potentially harmful for people experiencing trauma, whether it happened five days ago or five years ago

- People experiencing grief from gun violence have been let down by systems that have tried to help them in the past

- Journalism won’t solve the problem alone. But reporters can do a better job showing up, building trust, and listening to community members’ ideas

I’ve spent the last eight years as a reporter for two different daily media outlets. Being given two months to report in communities without a set deadline is practically unheard of.

But with an issue like gun violence, it’s absolutely necessary.

In my last two roles, I covered health and medicine. So I’m used to looking at big, systemic problems and the way they fracture the lives of Black and brown communities. I’ve developed an approach for talking to people who’ve recently experienced trauma, which was crucial during the two years I spent reporting on survivors of sexual assault. I’ve become intentional about what I cover, and committed to designing journalism with the potential to make positive change for the people at the heart of the story.

So I’m here, ready to listen to people on the ground as we all slowly work toward a safer, stronger Philadelphia.

Taking back the village

Gilbert Coleman stands up from his seat in the Nicetown Community Development Center meeting room and stares three uniformed police officers directly in the eyes.

You can see his years in his face. He’s a block captain in this neighborhood, and he is angry.

“I just wanna sit on my porch, drink my coffee, and read my paper,” he says.

The block is changing with the constant threat of violence, and he says people aren’t as comfortable sitting on their stoops as they once were. A neighborhood librarian tells me community members are still rattled from a seven-hour shooting standoff in 2019 that had people running for shelter. She says there’s a bookshelf that still has a bullet-hole in it from a different shooting that year.

Gil is retired, so he sees everything. He describes the guys who are inciting violence in the neighborhood, the way they’re posted up on corners,silently exuding control.

“They got chairs!” he shouts, near tears.

There’s a feeling of powerlessness among residents of these neighborhoods, a sense of lawlessness that allows crime to run rampant. People talk to me about it all the time.

I’ve watched them clean up their sidewalks and hold protests against the 24-hour “stop ‘n’ go” markets that they say create an environment for violence. I’ve watched them build community gardens to combat the feelings of neglect that prevail in neighborhoods riddled with sidewalk cracks and garbage piles.

These are largely Black communities, and the crumbling public infrastructure dates way back to 1930’s-era redlining and the intentional disinvestment in non-white areas of the city. Residents want reparations. They want clean parks and renovated recreation centers. They want a crackdown on abandoned vehicles, and a revamped policing strategy, where officers get out of their vehicles and walk the streets instead of sitting in their cars. (The city has vowed to increase foot and bike patrol this summer.)

The City of Philadelphia has a number of programs underway designed to return a sense of security to Philadelphia’s most crime-impacted neighborhoods. They’ve introduced a mechanical street-sweeping program beginning in the areas with the most shootings, and they’re planting gardens in vacant lots. They’re spending millions of dollars in bond money to make desperately needed repairs to parks and playgrounds.

But many residents say they aren’t seeing the changes, and they’re antsy about a summer shooting surge.

So they’re taking neighborhood safety into their own hands.

On a Friday night this March, I put on a high-visibility vest and joined Philly Truce, a one-year-old violence prevention nonprofit, on a walk through the Overbrook area of West Philadelphia. Mazzie Casher and Steven Pickens have been out on the streets most weekends, handing out brochures for the Philly Truce app, which aims to build a network of volunteer conflict mediators.

While we’re walking, Casher approaches a woman sitting on her front steps.

“We’re Philly Truce, it’s gun violence intervention,” he says. “No police involvement, anybody gets pulled into somethin’ they don’t want to be in, we can try to help them get out.”

Casher and Pickens represent just a slice of the effort to build a network of conflict mediators across the city, though there are mixed opinions on who should do this work and what the best practices are. Some organizations and schools are teaching young people how to resolve their own disputes. A city crisis intervention program has 59 trained workers out on the street seven days a week, ready to de-escalate a heated situation should they come across it.

The city of Philadelphia’s Town Watch Integrated Services program provides safety training to community groups like Philly Truce who want to walk the streets. It also teaches groups how to launch “Safe Corridors” programs, which recruit adult volunteers to walk children to and from school. The idea is to make kids feel safer, which can boost mental wellness and improve school attendance.

Frontline Dads, a father-led nonprofit, provides a similar service after school each day, as does the longstanding gun violence prevention group House of Umoja.

Tyrique Glasgow, director of the Young Chances Foundation, is trying to make an entire block of South Philly’s Grays Ferry neighborhood a safe zone for kids. He’s got a resource center on the corner of Tasker and 27th streets, where he distributes food on a daily basis. A ways down the block, there’s a new community garden, where he hopes to run programs this summer. He has plans to pave over the sidewalk and build a corner basketball court.

Glasgow believes making these changes will deter shooters.

“Where there’s trash on the corner, it’s easy to stash your gun there,” Glasgow told me while working a fence post into the ground at the newly-established Tynirah Borum Community Garden. “But if you see a safe place where kids are growing fruits and vegetables and playing basketball, you might say, ‘I’m not gonna put my gun there, let me go down the street’ … it also may empower the kids to bring more positivity to the community.”

These are just a few of the dozens of examples I’ve seen in the past three months of people looking out for one another’s safety, trying to beautify their blocks, and encouraging each other to take action. People often tell me they’re “taking back the village” — trying to find their way back to a world where people look out for one another and invest in the success of the entire neighborhood.

It might seem like wishful thinking, but it’s in action here in the City of Brotherly Love. Now, the question remains: Will these patchwork efforts reduce citywide gun violence in the long run?

‘Everyone is in survival mode’

Somerset Avenue is an obstacle course of trash bags, discarded furniture, broken glass, and cracked curbs. I struggle to walk side-by-side with Pastor Carl Day as he strides from block to block, pausing often to wave hello to a neighbor.

A man in a red tee comes down from his porch — he’s just returned from prison and is interested in finding a job. Others roll down their windows to greet Day as they drive, or nod at him on their walk to the neighborhood corner store. Passersby give Day hefty high-fives. He embraces them with sturdy, tattooed arms.

Day is the founder of Culture Changing Christians, a nearby church that also serves as a resource center for men at risk of violence, including those who’ve already been involved with the criminal justice system. He’s hopeful that prayer, therapy, life skills, paid training, and some genuine emotional investment will help put the men he serves on a less dangerous path.

“The goal is to convince you to value your own life,” he said.

It’s a version of a strategy I heard a lot about on my tour: identifying people at risk of committing violence, including young people, and helping them choose alternatives.

For Day, that means getting guys into jobs, talking to them about substance abuse, and teaching them it’s okay to resolve conflict. In an ideal world, those guys find ways to care for themselves and their families that don’t involve picking up a firearm.

I don’t want to gloss over the truth here: These programs are band-aids on the gaping, festering wound that is systemic racism and injustice. Black Philadelphians have endured abuse for generations, and discriminatory policies contributed to the current disparities we see in housing, education, and employment. They are still living in a state of oppression and toxic stress.

We can’t change history. But we can try to put people in charge of their own futures.

It’s why Philadelphia needs Culture Changing Christians and similar programs — ManUpPHL, for example, and the Father’s Day Rally committee — to give people another option so they don’t resort to violence.

There’s another group of players in this fight: violence survivors, and the loved ones of those lost to gunfire. While pulling a trigger is often a split-second decision, the impact of a bullet has real and lasting effects for those left behind. I can’t cover this beat without talking to them about what violence prevention could look like.

Many survivors don’t get closure. The clearance rate for shooting cases in Philadelphia is 24% for nonfatal incidents and 48% for murders, according to the police department.

The city recently established an Office of the Victim Advocate to help families affected by violence navigate the criminal justice system and provide other support they may need.

I listened in as Adara Combs, the new head of that office, spoke to a group of gun violence victims and their families about her new role. She gave each of them the floor to talk about their experiences and ask her any questions.

The stories they shared were among the most brutal that I heard during the course of my listening tour. These are just a few of their comments:

“Two years, I stayed on my couch,” said one mother of the aftermath of her son’s death.

“The first four days were a black hole.”

“Trying to get help was a nightmare.”

“Nobody’s fighting for my son.”

But these women are pushing through this immeasurable grief, through tears and sleepless nights and moments of rage, to try to put an end to the violence. I’ve been at rallies where mothers demand the city take action, call on parents to check on their kids, beg shooters to walk away from a fight. They want desperately to spare others from the pain they’re currently living through.

Chantay Love is often one of the first people victims call after a homicide. She runs the EMIR Healing Center in East Falls, which provides support groups, education, yoga classes, and other resources to people impacted by homicide.

“Everyone is in survival mode right now,” she said.

As we sat in a back room — usually used for grief groups — she drew me a map of the way she sees victim support services in Philadelphia. The public health system, behavioral health system, school system, and law enforcement agencies are on one side of the map, in a column. Community groups are on the other side, with a circle drawn around them. Families are floating around somewhere in between, unable to access either type of service.

Love, like many of the nonprofit directors I’ve interviewed since I started, says it’s time to remove the lines around these organizations and provide navigators to walk people through the options available to them.

“We’ve got to change the landscape,” Love said.

And that gets to the core of what I want to do in this job: change the landscape of Philadelphia’s gun violence crisis by lifting up available resources and shining a light on unexpected solutions — both those that have been proven to work in other parts of the country and those that are only beginning to unfold in corners of Philadelphia that might otherwise remain siloed.

There are dozens more ideas I heard about on my listening tour that I didn’t even get into here: youth programming, job opportunities, relocation services, gun supply crackdowns, firearm purchasing restrictions, Cure Violence models, hospital-based interventions, school improvements, mental health, and drug addiction programs, just to name a few.

I believe focusing on a wide array of solutions is the only way Philadelphians can guide themselves to a less violent 2023, or 2024, or 2050. Nothing is going to stop the violence immediately, and there is no bringing back those we’ve lost. But shifting the narrative from hopelessness to hopefulness, injecting energy and attention into what’s working and connecting people at risk of violence involvement to the care they need could prevent tragedy from unfolding years from now.

I have to believe that’s true. It’s what keeps me in this work.

From myself, and newly added Report for America gun violence prevention reporter Samantha Searles, you can expect to see:

- Stories about everyday people working to prevent gun violence in their neighborhoods

- Follow-ups on city programs promised to improve public safety

- Analysis of research and evaluation on gun violence prevention programs and how they’ve worked in other cities

- Close looks at city, state and federal policies that could prevent shootings

- Explorations of external factors affecting Philadelphia’s crime rates, such as the gun supply

- Conversations about the cultural factors driving violence, including poverty, racism, addiction, housing, education and mental health

It’s a tall order, and I need the community’s help to do it. It’s why I began my journey with listening and relationship-building. I’m not an expert, and I would never claim to be. But I am an intrepid reporter who cares about the way my stories affect the people I write about, the impact my work has on the problem at hand, and — most importantly — the truth.

I need people affected by gun violence to help me understand the truth. I know that’s a big ask. In exchange, it’s my vow to follow trauma-informed community engagement practices to make sure that vulnerable people I interview leave their interactions with me feeling fairly represented and, if I’ve done my job right, empowered.

If you’d like to follow along with my journey, you can find my articles at WHYY.org

If you’d like to weigh in on the crisis and the types of stories you’d like to see about it, fill out our Hearken prompt below, or email me at scaiola@whyy.org.

If you or someone you know has been affected by gun violence in Philadelphia, you can find grief support and resources here.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.