West Chester hopes its plastic bag ban sends Harrisburg a message

The state moratorium calls for more study of regulating plastics. But many say the benefits are clear, and that it’s also a matter of local autonomy.

Listen 4:55

Kiran Schatz, 12, carries his school supplies home in reusable bags. The West Chester student and his classmates worked to promote legislation that would ban the use of disposable plastic bags in their town. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

This article originally appeared on StateImpact Pennsylvania.

—

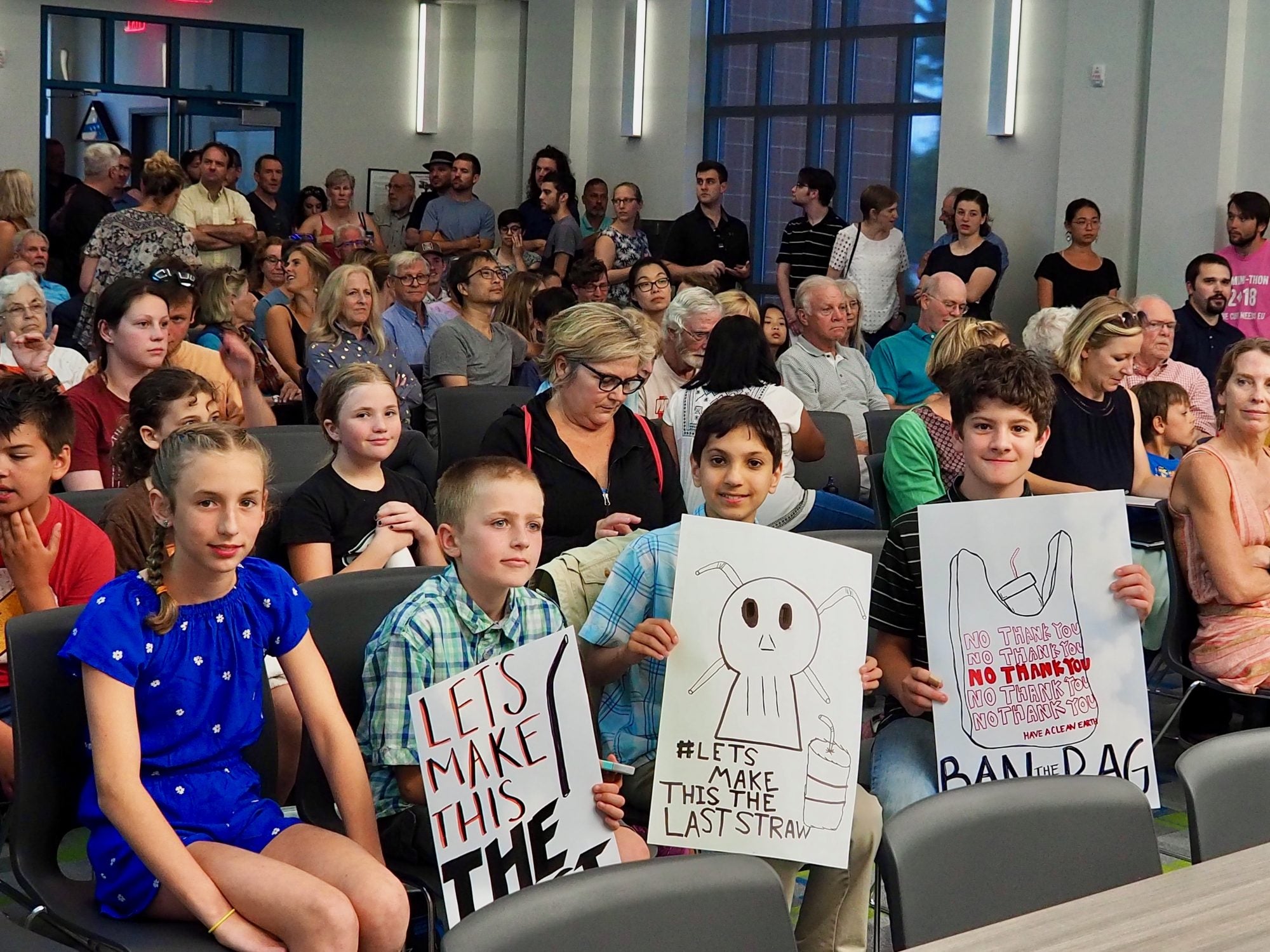

Council meetings in the Chester County borough of West Chester are usually not very well attended. But it was standing room only for the council’s July 17 public hearing about a ban on plastic bags and straws.

The room was packed because the bag ban, which previously had unanimous support from the council, had become controversial. Just a few weeks before the hearing, a budget-related state bill was signed into law in Harrisburg — and buried within it was a provision prohibiting towns like West Chester from regulating single-use plastic for one year.

West Chester Borough Council members wavered at the hearing — fearing a lawsuit if they passed the ban. But in the end, inspired by nearly two hours of impassioned speeches, they voted to pass it, with one change: The ban would not be enacted until the end of the state moratorium.

The state’s measure was enacted on the premise that the jury is still out on these types of regulations — whether they work, and what impact they have on the environment and the economy. The provision funds two studies looking at these impacts. But many, like the supporters of the ban in West Chester, believe the benefits of reducing single-use plastic are incontrovertible.

The idea for the bag ban was first brought to the Borough Council by a group of middle school students from West Chester Friends School. One of the students, Kiran Schatz, said in an interview he cared about the issue because he saw the harm plastic could do to wildlife.

“A lot of animals mistake it for food, and they’ll eat it or even just get stuck in it,” he said.

Kiran referred to shocking images in the news, like one of a turtle with a plastic straw stuck in its nose. This turtle, and another viral image of a whale that starved to death with 90 pounds of plastic in its stomach, has inspired action to reduce single-use plastic all over the world.

He also brought up other concerns about plastic bags — that they never completely degrade and just break down into microplastic particles. He said they cost the town money when they get caught in storm drains and sewer systems.

One of Kiran’s classmates, Isaac Harte, said the main problem with plastic bags is how they are made, using fossil fuels.

“We’re so tied into that ecosystem of plastic, and it’s really harmful for climate change,” Isaac said.

The students met several times over the summer of 2018 and conducted surveys of residents and businesses in the borough. When they presented their findings to the full Borough Council, they won it over. The council proceeded to write an ordinance that would ban plastic straws and single-use plastic retail bags, and place a fee on paper bags.

But before the council members could vote on it, the state enacted its moratorium. When Kiran’s teacher told him what happened, he said he felt cheated.

“I felt like we had already voted yes on it,” he said. “Just before we were going to pass it and enact it, it was just gone.”

A ban on bans

The moratorium was spearheaded by State Sen. Jake Corman, the Republican majority leader from Centre County.

“This was a way for us to take the politics out of it, do some research, and then come back, and let us make a more educated decision on how we want to move forward on this issue,” Corman said.

One reason he wanted the studies done, Corman said, is that his district includes Ferguson Township, which had been getting ready to pass a fee on plastic bags.

Steve Miller, who chairs the Board of Supervisors in Ferguson, said that he had no problem with the state doing more studies, but that he objected to the way the budget process was used.

“I thought that was sort of a backdoor way to stop municipalities rather than addressing it as a separate issue,” Miller said. “I suspect the governor wouldn’t have supported it if it had been addressed as a direct issue.”

In 2017, lawmakers did try to address it as a direct issue, with a bill that would have permanently banned plastic bag bans in Pennsylvania. Gov. Tom Wolf vetoed the bill, citing the Environmental Rights Amendment to the state Constitution.

But there’s another reason Corman called for more research: His district is home to a plastic bag factory, Hilex Poly, which employs about 160 people. He said Hilex tells a compelling story about its recycling program — it picks up used plastic bags and films from drop-off centers like grocery stores and uses them to produce new retail bags. The Hilex factory in Milesburg, Pennsylvania, makes bags with an average of 40% recycled plastic.

Do plastics bans work?

Phil Rozenski, vice president of public affairs and sustainability for Novolex, the parent company of Hilex, said banning plastic bags can have unintended consequences. For example, many people reuse retail plastic bags as trash bags, and without them, they end up buying more trash bags.

Rozenski cited a recent study of retail store data in California, which found that the sale of small plastic trash-can liners increased by 120% after bag bans were passed. These bags are often thicker than retail bags and are made from virgin plastic.

However, the study also says that bag bans in California reduced overall plastic by about 30 million pounds per year.

Rozenski said he’s glad the state is studying all kinds of plastic packaging because the issue of plastic in the environment and the ocean is not about plastic bags.

“They are almost a negligible piece of what’s out there,” he said. “Plastic has to be approached in a holistic way if we’re going to solve it.”

Assessing what kind of plastic is out there depends on what you’re looking at. Sherri Mason is a professor of chemistry and sustainability coordinator at Penn State-Behrend and has done a lot of research on plastic in the environment. With microplastics, which have been found in bodies of water all over the world, she said it’s nearly impossible to identify what the items originally were because you’re looking at something about the size of a grain of sand.

“That being said, every single person has seen a plastic bag stuck in a tree, stuck in a bush along the side of the road, blowing in the wind, rolling across the drive,” Mason said. “I talk to hunters in the forest far removed from any place selling plastic bags, and they find plastic bags.”

That alone tells her that plastic bags are a big source of the little plastic bits scientists find in water and soil, Mason said.. “Reduction is ultimately what we have to do,” she said.

But pollution isn’t the only problem bag bans are meant to address. Studies have shown that replacements for plastic bags, such as paper, cotton and reusable plastic bags, can have a larger carbon footprint than single-use plastic.

West Chester Mayor Dianne Herrin acknowledged that issue. She said what she takes away from such studies is that if you use a reusable bag consistently, there’s no question the environmental benefit is there. She said she’s been using the same reusable grocery bags for the past decade.

West Chester’s bold move

Herrin objects to the way Pennsylvania’s moratorium was passed, which she said violates the state Constitution. She believes that under the Environmental Rights Amendment, the borough should have the right to make those kinds of decisions and that too often that power is taken away from local municipalities.

“There are so many instances when local governments try to protect the health, safety and welfare of their constituents and their hands are tied. I mean, we’ve seen this with pipelines coming through the backyards of our neighbors, and there’s nothing they can do.”

Herrin and other bag-ban proponents worry that state lawmakers may extend the moratorium or try to make it permanent, as about a dozen other states have done across the country.

Senator Corman said West Chester’s decision complies with current law. “It’s just a one-year moratorium. If they want to move after that, there’s nothing in the law that prevents them from doing that,” he said.

The borough is second in the state to regulate plastic. Narberth placed a fee on plastic bags earlier this year. (Mayor Andrea Deutsch told WHYY News that there have been no challenges to Narberth’s law.)

“We feel accomplished, but there’s still a ways to go, and there’s other things that need to be done,” said Isaac, one of the students who requested the ordinance. “I think our main purpose of the ban was to ban plastic bags in West Chester, but [also] inspire other places and larger boroughs and towns to do what we’ve done.”

Several other Philadelphia suburbs that were working on ordinances regulating plastics, like Doylestown and Solebury, have put their votes on hold until next year.

But in Philadelphia, City Councilman Mark Squilla said he plans to amend his proposed plastic-bag ban to begin after the state’s moratorium, just like West Chester did. He hopes to have the council vote on the bill this fall.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.