‘This is not a Hahnemann situation’: Mercy Hospital owner exploring ‘healthy village’ concept, partnerships

Inpatient care services may not totally disappear from Mercy Philadelphia Hospital, if the right partners can be found.

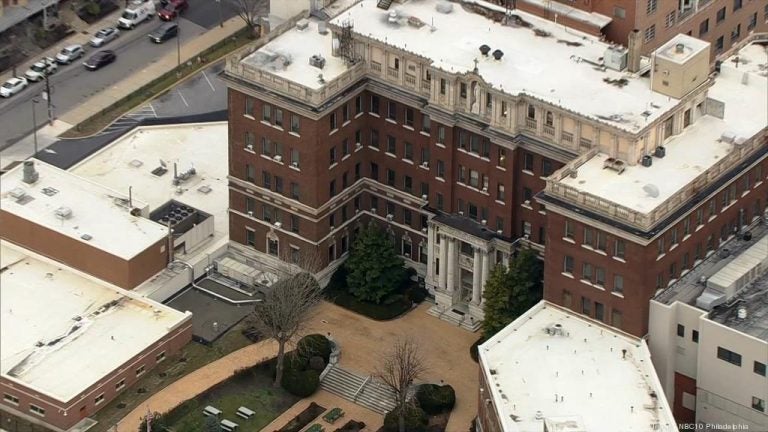

Mercy Philadelphia Hospital in West Philadelphia. (NBC10)

This article originally appeared on Philadelphia Business Journal.

—

Inpatient care services may not totally disappear from Mercy Philadelphia Hospital, if the right partners can be found.

James L. Woodward, CEO of Mercy Philadelphia’s parent organization Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic, said the health system is in discussions with a number of area health care providers about potential partnerships at the West Philadelphia medical center’s campus.

“Through a collaborative arrangement, we may be able to maintain key services and potentially bring new services to the hospital,” Woodward said.

Among the ideas being explored, he said, are maintaining emergency care and having a small number of inpatient beds available to support that department. Preserving inpatient and outpatient behavioral health programs is also being discussed. Woodward said he could not disclose identities of the potential partners while the talks are ongoing.

According to Woodward, many of the admissions at 157-bed Mercy Philadelphia come through the emergency department and involve treating patients with complex health issues, such as complications from diabetes, who use the ER as their primary care doctor. He said behavioral health care services are also an important community need.

Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic informed Mercy Philadelphia’s 900 employees earlier this month that it plans to end inpatient care services at the West Philadelphia hospital later this year.

Woodward said multiple factors went into that decision, including:

- Physical plant improvement needs at the hospital, which requires more than $100 million in renovations and facility upgrades;

- Declining admissions, which have dropped by 28% during the past several years;

- Difficulties in recruiting staff and doctors, which has resulted in Mercy Philadelphia and nearby Mercy Catholic Medical Center in Darby sharing one orthopedist;

- Financial losses, which are currently averaging $1 million per month. Mercy Philadelphia lost money in six of the past seven years.

“The math just didn’t add up,” Woodward said.

Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic, Woodward said, has no intention of abandoning the West Philadelphia community Mercy Philadelphia, formerly Misericordia Hospital, has served for the past 102 years. Early this week it opened a $2 million health center in West Philadelphia for Medicare recipients.

“This is not a Hahnemann situation,” said Woodward, referring to last summer’s sudden closing of Center City’s Hahnemann University Hospital by American Academic Health System. “This is drastically different. We are a faith-based organization guided by our mission and the West Philadelphia community is very important to us. The issue is how do we best tailor our services to meet the needs of the community.”

Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic, based in Conshohocken, is part of Trinity Health, a national Catholic health system that has its headquarters in Livonia, Michigan. Other local Trinity hospitals, in addition to Mercy Catholic Medical Center and Mercy Philadelphia, are Nazareth Hospital in Northeast Philadelphia, St. Mary Medical Center in Langhorne and St. Francis Healthcare in Wilmington.

In addition to talking with other Philadelphia-area health systems about potential partnerships, Trinity Health Mid-Atlantic is also working with the Ohio health care consulting firm Dynamis Advisors about bringing its “healthy village” concept to the Mercy Philadelphia campus.

The concept, Woodward explained, involves working with community leaders, politicians and nonprofit organizations to identify what community needs — health care and other — are not being met and bringing together organizations to work collectively to address those needs.

An example, he said, would be dealing with unemployment by working with a community college to provide job training on the hospital campus for people interested in becoming a certified nursing assistant or working as a tele-sitter, a new position in the health care industry in which a person in a remote location equipped with a video and audio system monitors patients at risk for falling.

Woodward said the future of the Mercy campus could involve a combination of partnerships with other health care providers for inpatient and outpatient programs, and the healthy village model. He said the health system is hopeful more definitive plans can be in place by late summer.

“We’re looking at what services are sustainable,” he said. “We are exploring a lot of options. We haven’t landed on any single one, yet.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.