Suburban Philadelphia district’s equity initiative provokes anger over critical race theory

Tredyffrin-Easttown was the site of historic segregation fight.

Bessie Cunningham, 99, was involved in the Berwyn School Strike in the 1930s. The strike is hailed as helping to lay the groundwork for Brown v. Board of Education. (Cunningham family)

This story originally appeared on Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Bessie Cunningham is 99 years old, and it is still painful for her to talk about why she never got beyond the sixth grade.

“I blocked it out of my mind. I didn’t want to remember nothing about it,” she told local historian Bertha Jackmon in an interview recorded May 25.

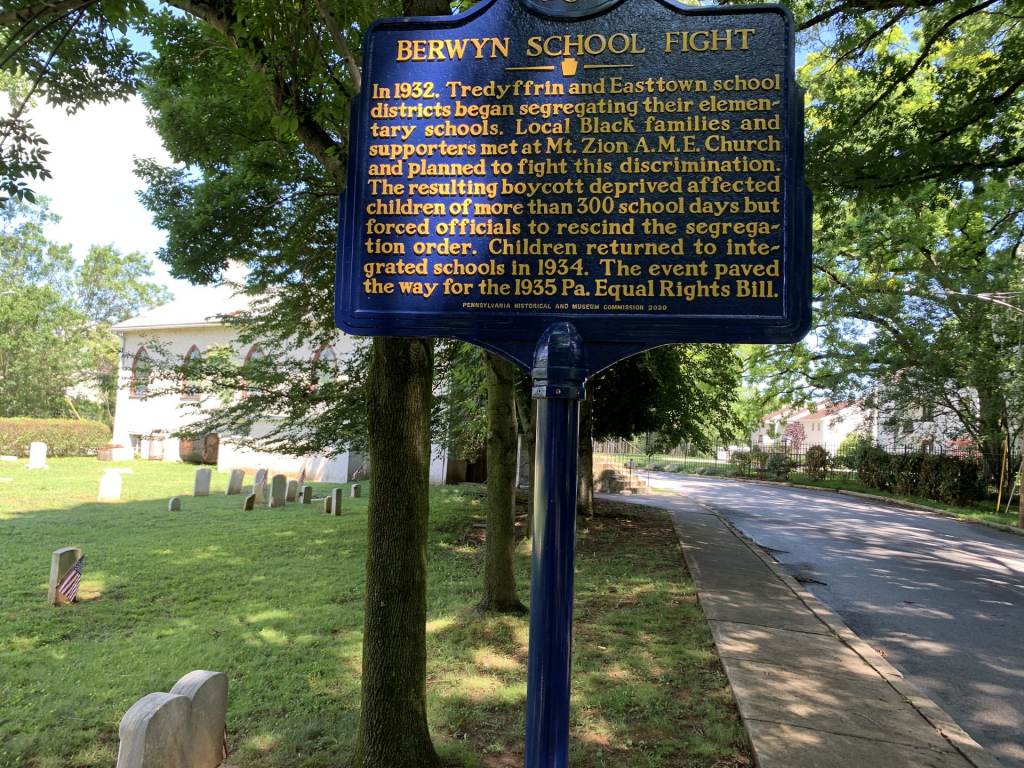

Between 1932 and 1934, Cunningham was among more than 200 Black children in the suburban Philadelphia townships of Tredyffrin and Easttown (yes, that Easttown) who were kept out of school by their parents to protest a board of education decision to segregate schools that until then had been integrated. The board denied them the chance to attend a newly built school that had been paid for in part with their tax dollars, declaring that students would be better off taught by a Black teacher “with their own kind” in the old building.

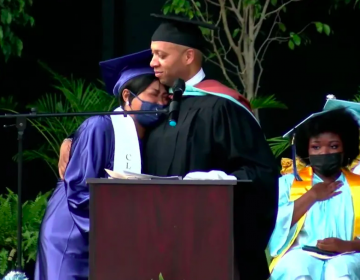

The so-called Berwyn School Strike was a defining moment in the area’s history, hailed as helping to lay the groundwork for Brown v. Board of Education, which outlawed school segregation 20 years later. Last November, it was commemorated with a historical marker at Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church, which served as a meeting place for the Black parents organizing the boycott.

The present-day Tredyffrin-Easttown school district — affluent, mostly white and Asian American — has sought to grapple with its past and present, embarking on an equity initiative in 2018 to retrain teachers, reframe curriculum, and promote classroom discussions about race and racism. Now, that effort is being attacked by some parents and community members as promoting critical race theory, an academic framework that studies how policies and the law perpetuate systemic racism. Conservatives have recently associated the term, as well as efforts to promote diversity, equity and inclusion, with leftist political indoctrination.

Like in most school districts, data show that the district’s Black students (2.6% of the enrollment, according to state data) are more likely to be disciplined than their peers and less likely to be in advanced courses, among other troubling markers.

“Every person’s authentic identity should be valued,” said Board of Education President Michele Burger at the unveiling of the historical marker, drawing direct ties between that fight and today. “We must eliminate barriers to racial equity.”

Monday night, as the board was scheduled to vote on an appropriation to continue the equity effort, more than 100 people jammed into the Conestoga High School auditorium at its first in-person meeting in more than a year.

“The fundamental mission of our school district must remain the success of all students,” said Superintendent Richard Gusick to open the meeting, discussing an equity statement adopted unanimously last October by the board. “When families and students express that their experiences… are at times negatively impacted due to race, I must remain committed to listening and being open to the fact that my own lens as a white male is broadened through hearing multiple racial perspectives.

“We must all be willing, myself included, to look with a critical eye how racial differences play out in our schools.”

Gusick’s statement was greeted with prolonged applause, but a vocal minority of the 29 people who spoke said the initiative was dividing the community and damaging children.

A few said that systemic racism doesn’t exist.

“I haven’t seen it,” said Gene Tompkins, who said he lived in the district for 40 years. “Quite the opposite. I don’t think you have proof of what you say. Show me the proof.”

Several parents, who are immigrants from China, compared the district’s equity initiative with the political indoctrination and violent persecution of the decade-long Chinese Cultural Revolution, from which they fled many years ago.

“Based on my personal and family experiences, there’s no systemic discrimination against any race in the states,” said Ying Yayne, who has lived here for 20 years.

Pennsylvania is among the more than 20 states that has introduced legislation limiting the discussion of race or bias in classrooms. In five states the bills have been signed into law. The bill was introduced by Rep. Russ Diamond of Lebanon and Rep. Barbara Gleim of Cumberland, both Republicans, who declared that “teaching our children that they are inferior or inherently bad based on immutable characteristics, such as race or sex, can be extremely damaging to their emotional and mental well-being.”

Many of the speakers, even some who acknowledged that racism does exist, raised questions about the Pacific Educational Group, the outside organization running the district’s antiracism initiative. They said they were being denied access to curricular materials.

“We are paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to teach racism,” parent Alicia Geerlings told the board. “It’s wrong. Our kids are afraid, they are anxious. If you have somebody in kindergarten that learns you’re the oppressor or the oppressed based on your skin color, how are they going to make friends?”

But several speakers described their own experiences with racism and discrimination.

“Before you adopted this amazing program…my children were called the N-word every day,” said parent Anita Friday. “There were scars they continue to experience. I truly applaud the work you’ve done so children who look like mine don’t have to cry, don’t have to feel ‘less than.’”

Friday’s children attended schools in the district years ago, but Un Kyong Ho described something that happened this month, at Valley Forge Middle School’s graduation. Her daughter, who is Asian American and white, she said, was sitting among “a group of white boys who spent the ceremony making fun of their peers with South Asian, East Asian, African and Middle Eastern and other non-western names, as well as their trans and LGBTQ peers.”

Opposing the district’s initiative, she said, “is protecting the right of your children to diminish and dehumanize their peers who they perceive as different from themselves. I commend the district for this commitment…I personally have been waiting my whole life for this.”

Rising junior Anish Garimidi said that he and his friends “have experienced racism from students and from teachers. The diversity work has been a boon for students of color like me who want to have these conversations…systemic racism is real and plain for all to see.”

Amer Sajet, a board member of the state American Civil Liberties Union, urged the accurate teaching of history. “When I grew up in Pakistan, all we learned about was what a great job Pakistanis are doing, we never learned about India. We were brainwashed by what we were taught in public school.”

Dante Coles, a former student and now a parent, referenced the 1619 Project, which reframes American history from the time the first enslaved Africans were brought to colonial Virginia. “Now, people are taught only certain things about history, things chosen by people who don’t look like me…a lot of white people really don’t want to learn the truth about America.”

Burger, the board president, calmly quelled occasional outbursts from those in the crowd. “You may not shout, you may not get up and yell,” she said at one point. At the end, she reiterated that the board, as part of its consent agenda, would be “approving workshops to continue our equity initiative. We are doing nothing that addresses critical race theory.”

She added: “What’s dangerous is when we stop listening. That is the work that is taking place in classrooms, having conversations, showing respect for each other, and trying to understand someone else’s experiences.”

Cunningham and Esther Long, 97, are the only known student survivors of the 1930s school boycott, according to Jackmon, Mt. Zion’s historian. Staying out of school for so long “had a terrible impact on my life,” Long said in an interview Tuesday, although she is proud that she managed to catch up, graduate high school, and become a nurse.

She feels that she and the other students “paved the way” for others to have more opportunities. “We laid the foundation so that things could be better for them,” she said.

The Black parents during the school fight ultimately prevailed, with the help of the NAACP and famed Philadelphia attorney Raymond Pace Alexander. Though it would seem that the law was on their side — the state school code clearly prohibited school districts from making “any distinction whatever” due to race — the case dragged on for two years, during which many parents were fined and jailed for truancy.

Still, they held out. Finally, the state attorney general, who was running for governor, agreed to settle in a bid for Black voters. Students could resume going to school with white students.

But many, like Cunningham, never went back, embarrassed to be put in classes with much younger children. “Not that I couldn’t keep up,” she said. “But they wouldn’t let me.”

And at the age when she should have been reading books and doing her arithmetic, making friends and being a girl, she was instead “on my hands and knees,” scrubbing the cement floor in a white woman’s house down the street for 25 cents a day.

“I didn’t play with nobody,” she said. “I worked.”

Despite that, she says her life has been blessed. She raised five children and for many years worked for the Burroughs Corporation, which had three local plants for the manufacture of early computer systems.

Cunningham said the experience of the boycott, and how it made her feel eight decades ago, still resonates inside her. “I don’t know whoever started that ‘You’re Black and I’m white.’ I’m a person, so are you. God created all men equal, it’s what the Bible said.”

Said Jackmon, the historian: “Even with the advances, institutional and structural racism is still in place. I would say the school fight continues.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.