Remember Asian-Americans in those cultural-competency conversations

“Where are you from?”

“You speak great English.”

While these statements no doubt can come from a good place from a non-Asian-American trying to break the ice or even make nice with an Asian-American, the words can hurt.

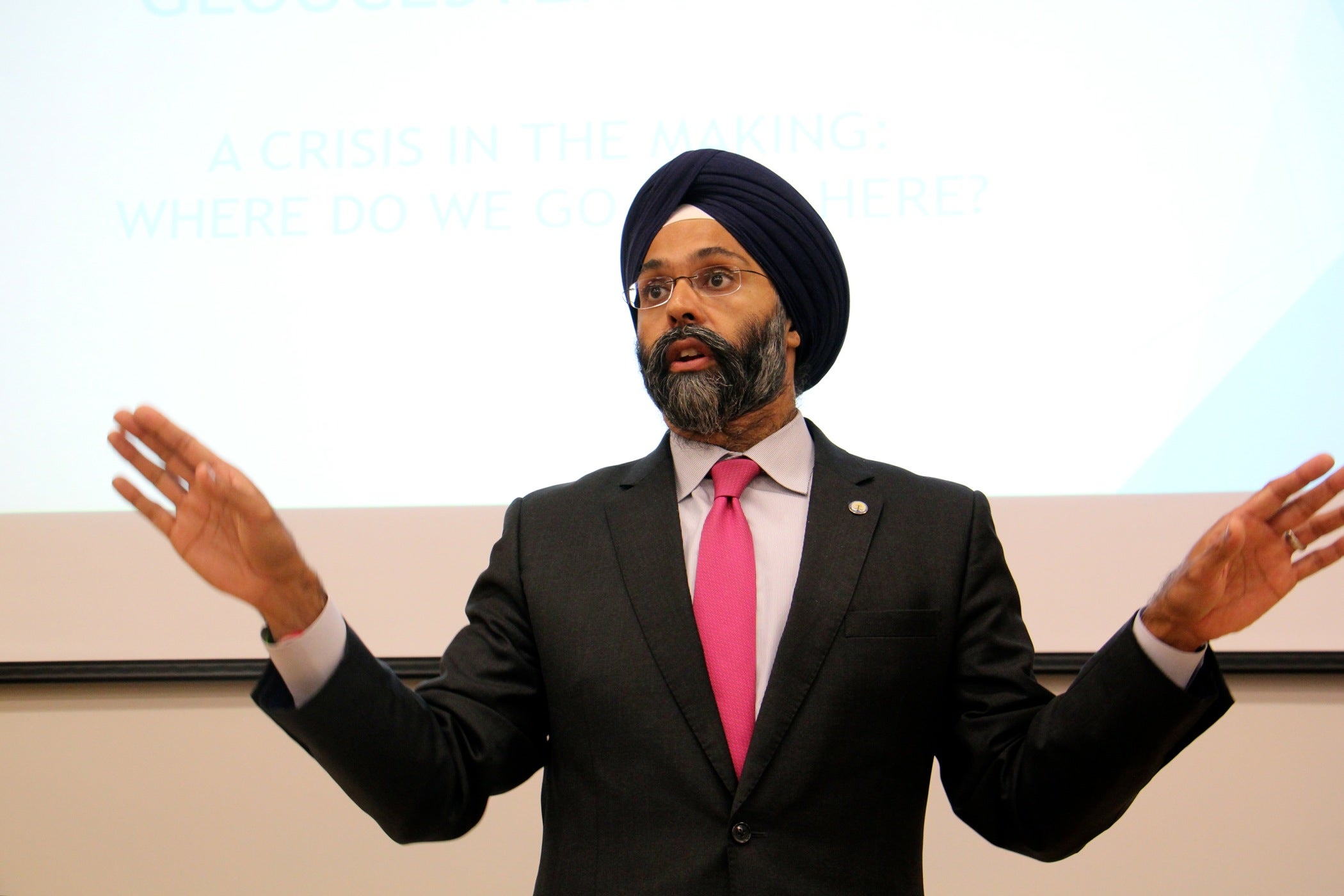

In addition to the unintended hurtful words, how about intentional hateful words and bullying: Ching Chong; slanty-eyed, which young Asian-American children and teens hear at school; and more recently, “Turban Man,” said publicly on the radio and aimed at the Sikh attorney general of New Jersey?

And then there is the hurt that pains the pocketbook: not getting a job, or once already inside an organization, not getting promoted to a leadership position because Asian-Americans may be perceived as not having traditional leadership attributes such as assertiveness, initiative, influence, or comfort with conflict. That perceived lack of desired attributes may hold Asian-American women back even more.

April’s incident at a Philadelphia Starbucks has — yet again, and rightly so — resulted in discussions of race. Yet on the East Coast and in Philly in particular, talk of race, ethnicity, diversity training, and cultural competency is often synonymous only with black-white relations. Asian-Americans are not seen as part of the equation or as a necessary perspective for a full conversation.

However, recent incidents regarding Asian-American realities – for example, the Harvard lawsuit regarding (non)-admission of Asian-Americans, and the name-calling on the radio directed at New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir S. Grewal — show how we need to include Asian-Americans in diversity conversations. Diversity/inclusion issues encompass more than black-white issues, and so diversity trainings, op-eds, and demonstrations can and should include not only Latinx and Muslim issues, but also the lived experience of Asian-Americans.

Let’s treat ignorance and racism like a disease. Public-health practitioners believe that following these three steps can help end a disease: raise knowledge, which may change attitude, which results in behavior change. Maybe if we perceive ignorance and racism as a disease, we can try to eradicate it by raising knowledge (in this case about Asian-Americans), which might lead to changed attitudes, which might lead to changed behavior such as promotions and acceptance to leadership positions in the workplace.

From small daily micro-aggressions (“You speak good English,” or, “Asian women are submissive and obedient”) to deep a history of major ones — internment of Americans of Japanese descent; separation from families left behind in the country of origin for Chinese, Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians; many children growing up faster than we should have because we had to interpret medical interviews for our parents and fill out insurance and immigration and job-application forms — the experiences have both traumatized us and enriched our ability to be resilient.

For these reasons, for-profit companies, nonprofit organizations, and government institutions may want to raise awareness about the Asian-American experience with their employees, staff, and students. That education may result in changed attitudes about the contributions as well as the challenges of immigrants and refugees. And the shift in attitude may result in changed behavior – jobs, promotions, and equally important, collaboration and coalitions among diverse groups once we realize we have similar experiences.

My daughter, who is African-American, was house sitting for a neighbor and took her laptop with her. As she walked out, she thought, “I hope anyone who sees me doesn’t think that I’ve stolen this computer.” However, if I walk out with one, I may be stereotyped not as a thief, but, of course, as an excellent tech-support person always with his laptop – a stereotype nevertheless.

People of color are constantly on guard, hyper-aware of how looks and actions might be perceived, and they intentionally go out of their way to smile to reassure that, indeed, they do belong.

Stereotypes – positive or negative – are exhausting. They are detrimental to all, not just those affected. So… what to do?

Offer training to help everyone stretch his or her thinking, though with some caveats: Mandatory diversity training may have the opposite effect. Think carefully for whom and how the training is conducted. Engage employees, staff, and students, rather than coerce and mandate.

Conduct thoughtful outreach and recruitment to ensure a diverse workforce in which everyone is contributing to the mission of the organization. Employers should play to staff strengths rather than weaknesses.

Once in the workplace, develop mentoring programs and affinity groups — for women, Asian-Americans, African-Americans, and Latinx.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.