Philly exhibit follows still-life movement over 150 years

“Flowers are restful to look at,” said Sigmund Freud. “They have neither emotions nor conflicts.”

The pioneering psychologist’s aphorism is vividly contested in “The Art of American Still Life: Audubon to Warhol,” now at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The exhibition tracing the evolution of the painting genre suggests still life in America was anything but static.

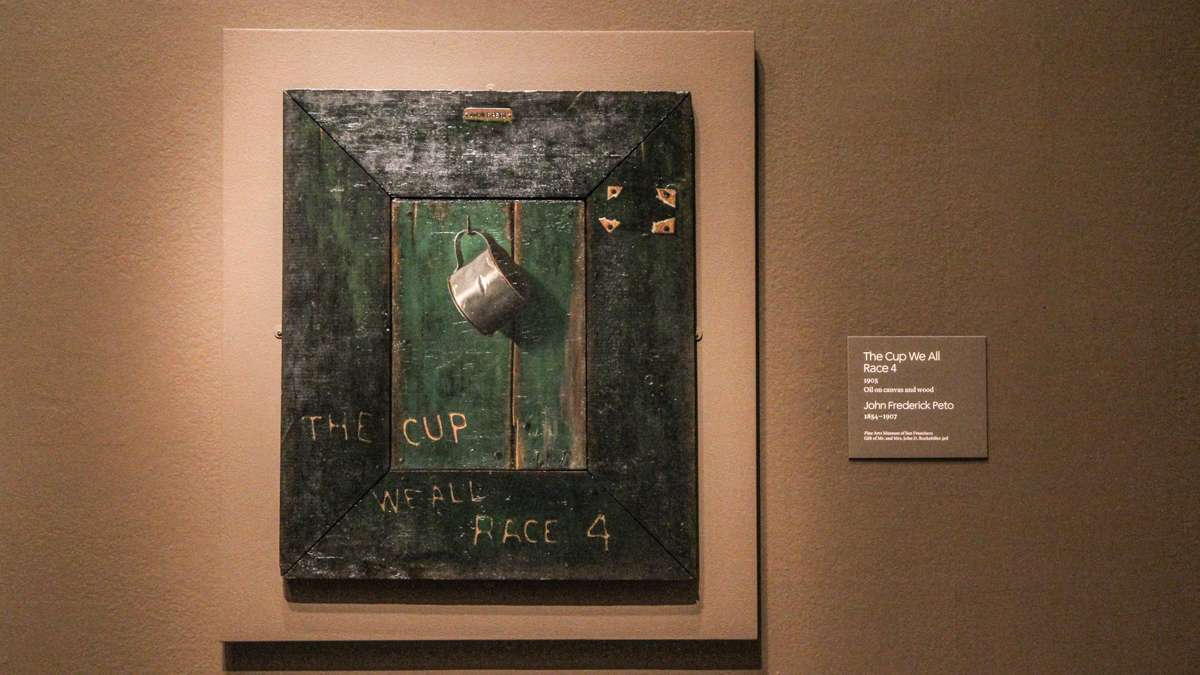

Rather than flowers on a table, the show has guns and trains, exploded watches and a pack of smokes, opulence and rot.

The show starts with Audubon, whose huge 1827 publication, “Birds of America,” attempted to record every winged species in the United States. Its 435 life-sized paintings were a scientific undertaking to define the character of America through its fowl.

Audubon’s work stands somewhere between science and art. He carefully staged his bird specimens — by posing their bodies with wire — to assemble an image representing multiple views of the bird in an accurate setting.

Though accurate, the paintings are highly manipulated.

“He considered himself an artist,” said curator Mark Mitchell. “The book is not organized by taxonomy, it’s organized aesthetically. He was not interested in a scientific, ordered approach; he was interested in an artistic representation of nature.”

By the mid-19th century, science went out of fashion in regard to still life. The second part of the exhibition features fantastically lush fruits and flowers, expressing painterly ideas of color and texture, and patrons’ ideas of narrative and status. Flowers took on social and political meanings (native plants were considered patriotic), and abundance implied a good story.

Mitchell has set up two sitting areas in the show — with couches, tables, and upholstered chairs — so visitors can better sit with one another and discuss the paintings. Still life is, by nature, a drawing room genre. These are images meant to decorate, fascinate, and fit over the couch, a few clicks down from the drama of history painting or the sublime awe of Hudson River landscapes.

“This is an exhibition that really tries to bring forward the way in which still lifes created conversations among Americans at different times in history,” said Mitchell. “Conversation is a really integral part of this exhibition.”

The show includes what was once the most popular painting in the world. “After the Hunt” by William Michael Harnett is a tromp l’oeil featuring the tools of a hunt hung on a wall — a flintlock, a horn, a crushed hat, a dead rabbit.

Saloon owner Theodore Stewart bought it in 1885 for $4000 — a huge amount at the time — to be displayed in his Manhattan bar. It got international press, the London Times calling Stewart’s Saloon a “mecca.”

“People came by the thousands every week. He added lady’s hours to meet the demand. It was so wildly popular, it was reviewed across the globe,” said Mitchell. “And … it’s a bar.”

The still life is, above all, a genre of things. The paintings are close examination of objects, often divorced from their context, to enable an appreciation of their unique physical attributes: their thing-ness. America, in its early years, was a country of raw material: iron, cotton, timber, tobacco constituted an economy of things.

“Anxieties about the autonomy of the nation’s object culture persisted,” writes Bill Brown in an essay for the exhibition catalogue. “Only the manufacturing sphere could enable a politically independent population to achieve cultural independence.”

By the late-19th and early 20th century, still lifes were becoming paintings of things that do things. Charles Sheerer painted the undercarriage of a steam locomotive (“Rolling Power,” 1939) and Gerald Murphy painted a large abstraction of the mechanism inside his pocketwatch (“Watch,” 1925). Alexander Calder’s “The Water Lily” is a still life that does not stay still; the weighted mobile sculpture shifts with the slightest movement in the room.

The show comes up to Pop art, with the Brillo Pad boxes by Andy Warhol, an artist who fetishized staring at objects. (His film “Empire,” not included in this show, is a marathon still life experiment.) Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain” is included in the show as the most literal still life: the porcelain urinal, pulled from real life, is propped up on a pedestal for your consideration.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.