PFAS chemicals found in drinking water nationwide, report says

In Philadelphia, the survey found two of the most commonly researched PFAS chemicals at levels far below the EPA’s recommended limit.

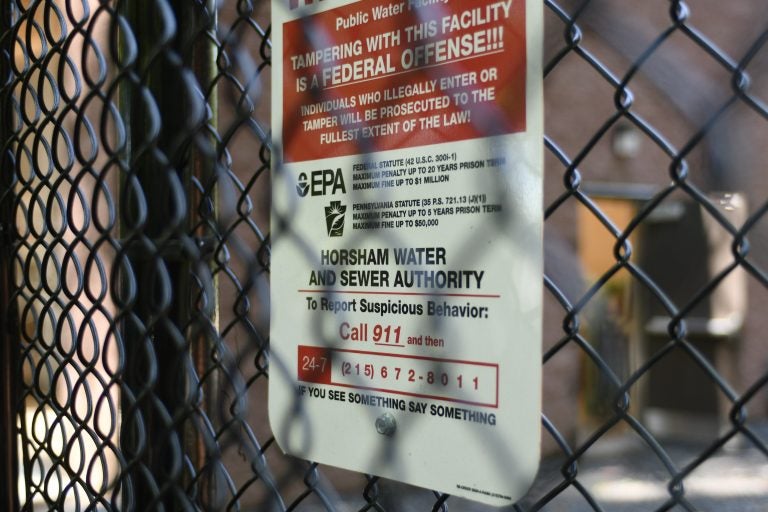

Detailed view on the newly installed system to filter out PFAS Forever Chemicals at Well #2 of the Horsham Water and Sewer Authority facility in Horsham, Pa., on August 22, 2019. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

A survey of drinking water across the country detected some level of PFAS chemicals in all but one sample.

In Philadelphia, two of the most commonly researched PFAS chemicals, PFOA and PFOS, were detected at 7.7 parts per trillion and 5.3 ppt — levels far below the Environmental Protection Agency’s recommended limit, as well as below New Jersey’s more stringent controls.

The EPA currently has a recommended limit of 70 ppt for PFOA and PFOS combined. New Jersey has established its own maximum contaminant level for the chemicals at 14 ppt for PFOA and 13 ppt for PFOS.

Also known as “forever chemicals,” PFAS are a toxic class of chemicals and include thousands of compounds used to make everything from nonstick cookware to water- and stain-resistant clothing. They do not break down in the environment. They also are used in firefighting foam, which resulted in contaminated drinking water around military bases nationwide, including former locations in Bucks and Montgomery counties. Exposure is linked to some cancers, as well as high cholesterol and thyroid problems.

The Environmental Working Group, based in Washington, D.C., rolled out its report on Wednesday with the support of actor Mark Ruffalo, who stars in “Dark Waters,” a movie about PFAS contamination in Parkersburg, West Virginia. Ruffalo put the blame on manufacturers such as DuPont.

“It’s time to end industrial releases of PFAS into the air and water, and it’s time to end needless use of PFAS in everyday products like food packaging,” Ruffalo said on a call with reporters. “It’s time to filter PFAS out of our drinking water. And it’s time to clean up legacy PFAS contamination.”

The Environmental Working Group said it tested just one sample of Philadelphia tap water for 30 different PFAS compounds and found 11, with a combined total of 46.3 parts per trillion. The group thinks the limit should be as low as 1 ppt.

There is little to no research on the health impact of exposure to most of the PFAS chemicals. But David Andrews, a senior scientist with the Environmental Working Group and a chemist by training, said enough evidence of harm exists for the few compounds that have been studied that the rest should be treated similarly.

The group says the report is meant to highlight the ubiquity of PFAS in the environment.

The Philadelphia Water Department says monthly tests for PFAS over a yearlong period in 2013 and 2014 consistently found levels of PFAS well below the EPA’s recommended limit of 70 ppt for a combined PFOA and PFOS. The department said it continually monitors waterways that feed its drinking water systems for PFAS chemicals. It plans to publish its findings later this year.

The Water Department’s manager of watershed protection, Kelly Anderson, said the preliminary results of the department’s own testing show levels of PFOS and PFOA continue to be below the EPA-recommended limit, and she questioned whether the Environmental Working Group used rigorous scientific methods when testing a Philadelphia sample.

“We understand this is an emerging national, global and regional issue,” Anderson said. “We take drinking water quality and public health very seriously. We are very committed to using sound science. There’s a lot of questions about how they went about doing their samples and methodologies. We have to follow very strict standard operating procedures. It’s unclear what practices the EWG took to adhere to those same scientific methods.”

Anderson said the EWG did not contact the Water Department or inform it of the testing and said the report mischaracterizes the safety of Philadelphia’s tap water.

“I feel very comfortable in the safety of the water we’re delivering to our customers,” Anderson said. “I drink the water and stand by its quality.”

States across the country, including New Jersey, have set limits far lower than the EPA’s. Pennsylvania is currently examining its own regulation of PFAS. The federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recommended limits far stricter than the EPA’s.

In a statement Wednesday, the city Water Department criticized the Environmental Working Group’s report as having too small of a sample size, lacking transparency, conflating the results and deviating from the peer-review process. (The report is not published in a peer-reviewed journal.)

“The ability to detect the presence of these compounds is advancing faster than the ability to understand their public health implications,” the Water Department said in its statement. “Advances in analytical methodologies allow us to detect concentrations in the parts-per-trillion (ppt) magnitude — the equivalent of a single grain of sand in an Olympic-sized swimming pool. The science around many aspects of these compounds, including potential public and environmental health implications, is evolving.”

“As the science surrounding PFAS is constantly evolving, we’re working to ensure that we are following the latest scientific developments so we can best protect our drinking water for generations to come,” the department said.

Drinking bottled water is not a solution, according to the group, as it is not regulated and there’s no guarantee that bottled water would contain fewer PFAS chemicals than public water supplies.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.