What a difference a two hour drive can make.

Students in Erie, Pa. attend a public school district that’s teetering on the brink of collapse.

Staffing has been downsized to bare-bones levels. Many of the schools are badly in need of repairs. And the superintendent has proposed shuttering all high schools.

The city district, though, is surrounded on all sides by better-resourced suburban schools that serve less needy children. This is the hallmark of Pennsylvania’s K-12 landscape: stark resource discrepancies between schools in different zip codes.

In 2014, the U.S. Department of Education labeled Pa.’s system “the most inequitable in the nation.”

But if those students in Erie were born just two hours north in the Canadian province of Ontario, they’d have a completely different outlook.

That system — though close geographically, and similar in terms of size and overall levels of diversity — offers a distinctly different vision of public education.

In this five-part Keystone Crossroads’ series, with input from stakeholders on both sides, we study that divide.

Welcome to St. James Town

Fourth grader Taki Alaid knows too well what it means to live on the run. He and his family fled Syria in 2014 in the midst of the ongoing civil war. Alaid vividly recalls the night they escaped.

“We had to crouch and they were behind us. They had flashlights,” he said. “Then a car came and took us to Jordan.”

From Jordan, Alaid and his family eventually made it to Toronto, where he was enrolled in Rose Avenue Elementary.

And there, he’s come to know safe harbor.

The school sits below the tight collection of towering apartment buildings that make up St. James Town — a poor, jam-packed, and extremely diverse neighborhood in Toronto. Locally, it’s known as “the world in one block,” and the student body reflects that.

“Our school community mainly comes from Pakistan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka. We’re getting a number from the Middle East now, so Syria, Iraq, Ethiopia” said principal David Crichton. “Many of them do not speak any English or are learning English, so that’s one of our challenges.”

Alaid was in that position when he arrived. But in two years, he’s picked up the language, and the school now feels like home.

“Now, I have so many friends,” he said with an infectious smile. “I know half the school.”

Based on the low-income levels and language barriers of the students at Rose Avenue, it may be natural to assume that the school is an academic low performer.

But quite the opposite. In most subjects, students at Rose Ave. score on par or better on Ontario-wide tests than the city and provincial averages.

Compared to Pennsylvania — where there’s a strong systemic correlation between test scores and family income — this is nothing short of shocking.

So what’s the difference? In part, Crichton says, it comes down to a widespread commitment to equity.

“There is a recognition that resources, be that money, be it people, be it my time, is absolutely focused on those kids who need additional support,” he said.

International accolades

That logic is making a difference not just at Rose Avenue, but across the province.

Over the past two decades, Ontario has become widely lauded for its education system.

High school graduation rates have steadily climbed, and the province has shot up the ranks on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which tests the skills and knowledge of 15 year-olds worldwide.

On the most recent PISA test, released this month, Ontario again posted impressive results, as did Canada at large. And the nation as a whole is celebrated for both high performance and relatively smaller achievement gaps between wealthy and poor students.

The USA continued a trend of middle-of-the-road performance on the PISA, with Massachusetts as a clear bright spot.

The Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study test (TIMSS), which gauges ability of 4th and 8th graders, also recently released results. The USA scored slightly better than Ontario in 4th grade, and the two systems were on par in 8th grade.

Pennsylvania participated in the PISA and TIMSS tests, but does not opt to be examined as a system in and of itself. So apples-to-apples comparisons between Pa. and Ontario on these assessments aren’t possible.

Based especially on its performance on the PISA, Ontario has been spotlighted as a worldwide leader in public education by McKinsey, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and, most recently, a bipartisan report from the National Council of State Legislatures.

Educators in Ontario cite many reasons for their success, but much of it comes back to this idea of “equity.” And from their vantage point, a state like Pennsylvania has been disregarding it at its own peril.

“I think you got it wrong in terms of looking at just basic issues of social justice,” said Crichton.

Sweeping school funding reforms

In the 1990s, the education system in Ontario looked a lot like Pennsylvania’s does today — with school funding based largely on local wealth.

But then Ontario made a few key changes:

It eliminated the local school property tax, and now all funding comes from the province.

It greatly reduced its number of school boards — widening the racial, social and economic diversity of each system.

And, crucially, it decided to provide more funding per-pupil to the school boards that serve students who face the greatest obstacles.

School boards get more money if there are more students who have low household income, who are raised by single parents, whose parents have low education levels, and whose families recently arrived in Canada.

At Rose Avenue, that’s translated into targeted to literacy programs to help students like Taki Alaid.

“I allocated four staff to ensure that every kid in grade one who wasn’t reading at grade level got daily instruction in a small group setting,” said Crichton.

It’s also meant the school could truly become the heart of the community. Rose Avenue offers programming for kids before and after school, and on the weekend. It’s a daycare, a pediatric center, and a place for new immigrants to adjust to life in Canada.

This need-based flow of resources is not what happens in Pennsylvania.

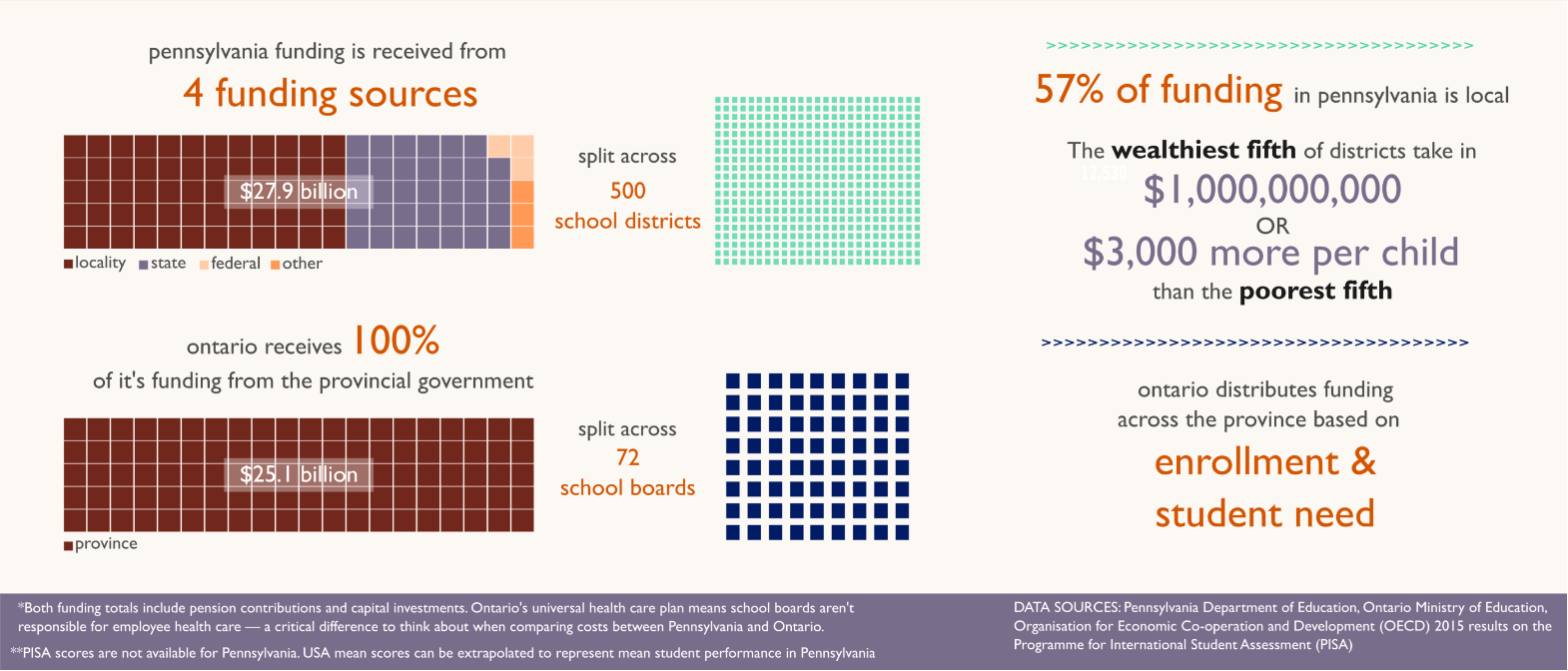

On the whole, most school funding comes from the locality — which means that districts start from a place of stark disparity.

About 35 percent of total public school funding in Pa. comes from the state. In theory, these resources act as a redistribution which should help level the playing field.

But, in practice, most state dollars are unscientifically distributed without systematically gauging student need.

This year, the state began to use a new student-based school funding formula that shares some attributes with Ontario’s system.

But lawmakers are only using it to divide a tiny fraction of the state’s main budget line for schools. So, overall, Pennsylvania’s system continues to favor families with the means to live in clusters of wealth.

The disparities in Pa. are even more pronounced because of its parochial nature.

Even though Pennsylvania has fewer students than Ontario, it has more than five times the number of school districts.

Some districts in the state are so tiny, poor and predominantly black that it’s hard not to question the rationale behind the boundary lines.

Delaware County’s Chester-Upland school district is ‘exhibit A.’ It is five square miles of deep, concentrated poverty with 7,000 mostly black students, a stone’s throw from whiter districts that are some of the wealthiest in the state.

By comparison, during Ontario’s major school board consolidation in 1998, Toronto merged with five surrounding boards. This created one massive 243-square-mile metropolitan system checker-boarded with wealth and poverty that serves an extremely diverse 245,000 students.

‘Model Schools’

In Ontario, the student-based distribution of dollars doesn’t stop at the provincial level. Within the Toronto District, more resources and support are systematically directed to the 150 neediest schools through the “Model Schools for Inner Cities” program.

This list is created using student-based factors similar to the province’s methodology.

Rose Avenue makes the list. As does Nelson Mandela Elementary, which is ranked the second-most needy school in Toronto.

Principal Jason Kandankery recently gave Keystone Crossroads a tour of Mandela.

“I’m sure as you did the walkthrough you kept waiting when you were turning the corner, ‘Now I’m going to see evidence that this is the second highest needs school,’” he said. “And I don’t think you saw it in terms of the built environment.”

In Philadelphia, there is not a list of schools ranked by indicators of student need, and the district doesn’t systematically direct the most resources to its neediest schools.

But if there were such a list in Philadelphia, it’s likely that the schools at the top wouldn’t look like Mandela Elementary.

There, not only has the building been rehabbed beautifully, but so has the entire neighborhood.

What was once considered a slum has been rebuilt into a socioeconomically-integrated neighborhood with new, gleaming public and private high-rise housing towers.

The dramatic change in that neighborhood was not without controversy, and some of the original residents were displaced. But it does highlight an important distinction that needs to be included with any comparison between Ontario and the U.S. or Pennsylvania.

Ontario’s commitment to equity in all realms — from healthcare to housing — has a tremendous effect on schooling. By and large, the students show up to school in Ontario with comparatively fewer deficits.

For instance, Toronto’s 25 percent child poverty rate — though high for Canada — is markedly lower than Philadelphia’s staggering 38 percent rate. And in Philly, families then have less access to social safety net programs.

The OECD highlighted how this dynamic contributes to education in its 2010 report on Ontario schools.

“The idea that health care and other social services are a right and not a privilege carries over into education, where there is a broadly-shared norm that society is collectively responsible for the educational welfare of all of its children,” said the report. “The combination of this norm with the protection afforded by the welfare state creates a climate in which school success is expected for all students.”

Within this context, combined with the equity of Ontario’s funding model, schools have a greater ability to deal with the issues that persist. And the job is buoyed even further by successful partnerships with philanthropies and community groups.

Mandela Elementary, for instance, provides doctors on site three days a week because of relationships the Toronto school board built with nearby hospitals.

“If we can bring that medical care into the school in a space they already feel comfortable to come into, we can expedite getting medical referrals and services for kids that most need it,” said Kandankery.

Philosophical divide

All of this, of course, costs money.

But here’s the rub: Pennsylvania actually spends more money on education per student than Ontario — but in a much different way.

Adding up all resource streams, the wealthiest 20 percent of districts in Pa. take in about a billion dollars more revenue than the poorest 20 percent — a difference of about $3,000 per child.

There are other crucial differences. Because Ontario provides universal health care to all residents, its school boards don’t pay employee health care costs — a major caveat to consider when comparing per-pupil spending.

Overall, though, the numbers highlight an essential philosophical divide.

Where Ontario values equality in the system; Pennsylvania values a family’s ability to maximize their own opportunities.

Top officials in the Toronto District School Board have a hard time fathoming Pennsylvania’s design.

“‘Education for all’ is Ontario’s mandate, and that’s what we stand behind,” said Helen Fisher, a leader in TDSB who helps run the ‘Model Schools’ program.

Many in Pennsylvania believe that families with greater means should have the greatest access to the best schools.

Fisher pushed back on this idea, arguing that Ontario’s system allows all families to pursue the best options for their children.

“All the kids will have that opportunity,” she said. “It’s a universal design.”

Keystone Crossroads explores the urgent challenges pressing upon Pennsylvania’s cities. Four public media newsrooms are collaborating to report in depth on the root causes of our state’s urban crisis – and on possible solutions.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.