When it comes to public schools, decades of research show the debilitating effects of concentrated poverty. So what’s the solution?

In the past few decades, policies in the U.S. have been crafted with the assumption that schools can overcome the immense hurdles related to student poverty by employing the right combination of better educators, better curriculum, and tougher accountability measures.

In short, the thinking goes, students in poverty aren’t meeting standards because their schools aren’t good enough for them. Proving the veracity of this idea often comes down to examining schools on a case-by-case basis. Looking at the overall trend, though, it’s clear that pursuing policies along these lines has been far from a panacea. Despite some encouraging examples, a stubborn gap persists between students of high and low income backgrounds.

Others argue that inequities would subside if schools in poor neighborhoods received a dramatic influx of financial support. They say students in poverty aren’t meeting standards because we’re not properly investing in their schools.

The debate over proposals in this vein is omnipresent. Decades of research shows that adding money to schools can make a difference for student outcomes, but only if spent well.

Another line of thinking says that both of these arguments ultimately fall short of what’s truly needed.

These advocates say leaders should focus on breaking underlying social inequities by finding ways for schools to integrate students of different socioeconomic, and often racial, backgrounds.

They say the best way to serve communities of concentrated poverty is to diffuse that poverty, and then surround disadvantaged students with the greater comprehensive supports and opportunities often available in schools of greater wealth.

Bolstering this point, racial achievement gaps in America were at their slimmest during the height of school desegregation efforts.

Historically, though, such attempts have resulted in a massive divestment from public school systems by parents of greater means.

That was the case during a recent attempt in Berlin, Germany, where parental blowback ultimately killed a plan to mix schools along socioeconomic and ethnic lines.

Even after the larger effort collapsed, though, one school’s integration plan succeeded. Keystone Crossroads went to Berlin to explore why.

Loopholes

When Heike Mohaupt-Wonnemann’s first child became school-aged, she did something that parents from her neighborhood almost never do: sent him to the other side of Bernauer street.

“In the beginning it was very funny, the way to school, because it was like one pupil — my son — going this way, and everybody else going that way,” she said with a laugh.

Mohaupt-Wonnemann, a native German, lives in Mitte, a district stratified between wealth and poverty. A mechanical engineer by trade, she and her three children live in the posh section of the district. The dividing line separating her side from Wedding — a mostly poor, immigrant community — runs along the site of the former Berlin Wall at Bernauer Street. Now, the street is known as a “social wall.”

“I discovered that there’s a big problem, because, on this side of Bernauer Street, there’s schools where everybody wants to go and they were all full,” she said. “And, on this side, the schools were empty and nobody wanted to go there.”

At the time, the area was the subject of a school integration effort that the Mitte government had hoped would improve outcomes for all. But the attempt was ultimately abandoned after many wealthier parents either moved out of the district, sent their kids to private school, or won legal challenges.

“They know what they want,” said Mohaupt-Wonnemann of the other parents in her neighborhood. “They know what they want for their children, and they think that their children are the best.”

As the integration effort was falling apart, officials at one of the schools on the poorer side of the divide, Gustav-Falke elementary, decided to take matters into their own hands.

“Forced measures normally don’t work,” said principal Sabine Gryzke. “People always find loopholes.”

Gustav-Falke elementary sits in Wedding, a mere block from the Bernauer Street social divide. Gryzke began teaching at the school in 1987, and she vividly remembers the week the Berlin Wall came down.

“I stood on the street with my class and watched,” she said, gesturing towards the former barrier. “And over there was a watchtower.”

Before reunification, the historically working-class, immigrant neighborhood of Wedding was part of West Germany. After the wall came down, as wealth and development poured into the formerly Soviet-held section of Mitte, Wedding’s poverty grew.

“All the parents with better educational background had left us,” said Gryzke.

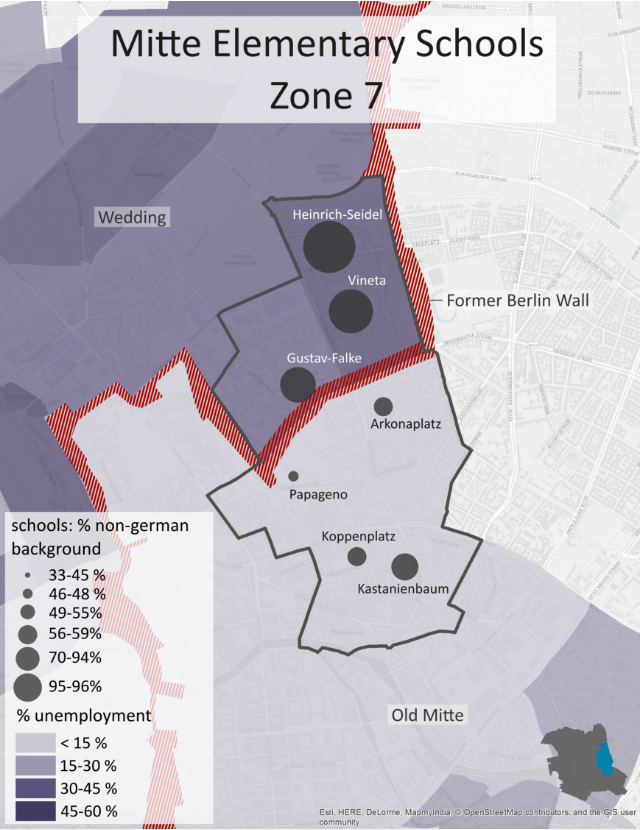

During Mitte’s integration attempt, the most contentious zone, number 7, included four elementary schools on the wealthy side of the “social wall,” and three on the poorer side — including Gustav-Falke.

By the time Mitte’s integration plan was announced, the differences between life on either side of the former wall was stark. And Gryzke says school leaders could do nothing to convince parents from the wealthier side of Mitte to consider Gustav-Falke as an option.

Enrollment had plummeted from a peak of 600 students to 350, and 95 percent of the children remaining had a mother language other than German.

“It didn’t matter what we did: music proposals, sport activities,” she said. “The wealthier parents stayed away because they were afraid that their children would have no chance here.”

‘The will of the parents’

So what did the school do to convince parents like Mohaupt-Wonnemann to opt in?

Something that ruffled a lot of feathers.

“Me, 10 years ago, I would have favored an idea where I put all the kids in buses and transfer them to the whole city,” said Maja Lasić, who represents the Wedding area in Berlin’s parliament.

Lasić is a point person for education policy for the Social Democrats, the mainstream left-wing party that had advanced the integration plan. After watching it get killed by backlash, Lasić shifted her view.

“At the moment, I would say that there is no solution which works if the will of the family is not accepted,” she said. “The thing we have to think about is how can we motivate the families to come by their own? How can we generate attractive environments in low-income communities so that high income families say, ‘Ok, it’s a low-income community, but the school is so good that I think it’s the best for my kid.’? And that’s the crucial approach.”

At Gustav-Falke, Gryzke began doing outreach to parents on the wealthier side of the wall — often showing up at pre-school programs playing the part of recruiter.

“We sat together with these parents and asked them what we need to do so that they would send their children to our school,” she said. “What is actually very important is that you work together with the parents. We are representing them as partners in charge of their children.”

Based on their feedback, Gryzke and her colleagues decided the answer was to create two distinct academic tracks.

Each year, all students take a German proficiency test. Those who score above 80 percent — no matter their social status — attend classes separate from the rest with a more robust English and science curriculum.

Although high schools in Germany have long tracked students by ability — with three discrete types of schools — doing so for primary grades stirred up controversy.

In recent years, the country has been moving away from this three-tiered high school system. It’s done so, in large part, because researchers have found that the system has exacerbated inequities between haves and have nots.

On the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), despite a positive trend for the past 15 years, low socioeconomic status still negatively affects students in Germany more so than the international average.

In this context, a proposal to begin tracking students in primary grades seemed, to many, a step in the wrong direction.

Gryzke believed the opposite. She argued that bringing these communities together in the same school — even if separated by ability — would ultimately yield better outcomes for all.

The slideshow below shows what life is like at Wedding’s Gustav-Falke elementary.

She specifically believed it would give her Wedding students, who had been effectively segregated by income status for decades, a better chance to escape poverty.

“That is the long-term goal,” she said, “but, on the way there, we need to have special classes as we otherwise wouldn’t get the [wealthier] parents.”

After getting a special dispensation from Berlin’s state government, Gustav-Falke was able to move forward with its model as an experiment.

Mohaupt-Wonnemann’s son was in the first cohort of tracked students, which included just a handful of children who lived on the wealthier side of Bernauer Street.

“We thought, ‘Ok, well, we will just try it,’” said Mohaupt-Wonnemann. “And the longer we are here, the happier we are.”

Seven years after being implemented, the program has attracted many more students from outside the neighborhood. Enrollment has ticked back up to 450. The share of students on social welfare has dropped — as has the share of children from families of non-German origin.

Emotional walls

Gustav-Falke’s program continues to be contentious, especially within other nearby schools in Wedding.

“We would never choose a system like that in order to attract more German parents. Never,” said Katrin Baumhöver, principal of Vineta elementary, another school on the Wedding side of the social wall that serves an even more impoverished community.

Her educational philosophy fundamentally rejects any model that doesn’t treat students equally — calling Gustav-Falke’s program a “two-class system.”

“Most important is the idea that each child gets accepted as they are,” she said. “Everybody is able to do something very well, and something else not. That’s how we work.”

Some of the Wedding parents at Gustav-Falke agree. Hassan Hijazi has lived in Berlin most of his life. He speaks Turkish, German and some English, and it bothers him that his 7-year-old daughter didn’t make the cut for the upper track.

“It is getting a bit separated,” he said. “That’s sad.”

Others parents from Wedding, though, say the program has been a life-line.

Rima El-Said, a single mother of four, came to Berlin from Lebanon in the 1970s. Her older daughters went to Gustav-Falke before the tracking program was implemented, and it often pained her to send them there.

“Because here at this school there were a lot of foreign children which hardly spoke German. Most of them were Turkish, and we are Arab,” she said. “So my daughter couldn’t understand anything in the classroom when they spoke to each other, and the performance level was very low.”

El-Said’s past makes her especially attuned to what’s at stake when it comes to schooling.

Growing up in Berlin, because her parents didn’t speak any German, she had to learn to navigate the school system largely on her own. She persevered in her studies anyway, and eventually became a pharmacist. She married a man who became a doctor, but then ended up separating from him, in large part, because of his conservative views regarding the education of their daughters.

Without him, she then gave up her career and found an apartment in Wedding where she could afford to raise her kids — including one who is disabled — full-time.

But she felt trapped by the school options. Gustav-Falke had disappointed her, and the schools on the wealthier side of Mitte didn’t feel ideal either. In theory, those schools were supposed to be integrating, but in practice, parents from Wedding could rarely secure a slot.

And even if that tactic had been successful, El-Said worried about how her youngest daughter, Duaa, would fare.

“I realized that my daughter wouldn’t fit in there,” she said. “She would be an outsider, as there is no mix. Just the way she looks is different.”

She considered finding another place to live, but changed her mind when Gryzke proposed the tracking program at Gustav-Falke. Duaa, who spoke very good German, tested well.

“I have no regrets,” El-Said said. “I wanted something different for my youngest daughter. I have invested so much into my children: time, education, myself.”

The tracking at Gustav-Falke happens in all six grades of the school. But every year, after taking the German proficiency test, new students from the lower track make it to the higher level.

So by the later grades, the classes are truly mixed culturally and socioeconomically.

“Those that weren’t that good, you now see that they are really becoming better and better in German,” said Sebastian Marquardt, who teaches the upper-level 4th graders.

On a recent day in Marquardt’s class, an ethnically-diverse collection of students collaborated on a project inspired by New York City’s One World Trade Center. In small groups, the students devised plans and built their own towers. The sound in the classroom was energetic and boisterous — a whir of creativity.

Judging by ability, it would have been impossible to guess which students lived where.

“I think this school really did a great job tearing down this kind of emotional wall in a way because it takes away these fears of mixing with other cultures,” said Marquardt. “I see it with the children in my class — that they really learn to explain the things that they maybe take for granted to other kids.”

In the context of Germany’s larger debate over its recent influx of refugees, Gryzke believes this sort of cultural mixing is essential, especially so, she says, for the newcomers.

“The most important thing is that they feel that they are part of this country, and want to give this country something back…” she said. “But only somebody who has a feeling of belonging does that.”

Role model or outlier?

For Maja Lasić, the politician, the progress at Gustav-Falke is encouraging. But she wouldn’t recommend mandating such an initiative in a wider net of schools.

“I think it’s the right approach for that spot, but it’s nothing I would transfer also to other schools,” she said. “The other schools have to find their own ways in their own profiles.”

Ultimately, Lasić believes these schools will have the ability to do this only when Berlin’s government doubles down on its commitment to its neediest neighborhoods.

“If I want to close the gap, then I have to treat the schools differently,” she said. “They must become our favorites.”

These schools already receive a greater share of resources depending on levels of student need, but Lasić says the system should go further to truly level the playing field.

She specifically laments that Berlin does nothing to incentivize its strongest teachers to work in its neediest schools. As a result, she says rookie educators are too often learning on the job in front of students requiring the greatest support.

Essentially, in the wake of Mitte’s failed integration effort, Lasić is now straddling the arguments made by both the more money and the more accountability camps.

“The good teachers, the ones with the highest ratings, are the first ones who can choose. And they all — most of them — go to areas where kids from wealthy families live,” she said. “What we need is additional motivation for good teachers to come to Wedding.”

This specific complaint is akin to one often heard in Pennsylvania — one actually exacerbated by the fact that teachers in the state are given fiscal incentives to work in clusters of wealth. Average teacher salary in Pennsylvania’s richest districts is nearly $16,000 higher than in its poorest.

This sort of disparity exists within school systems as well. In the School District of Philadelphia, the state’s largest, teacher pay fluctuates on a scale unrelated to the neediness of schools.

But addressing these sorts of underlying structural issues, whether in Philadelphia or Berlin, requires snapping into alignment a complex tangle of politics, policy and special interests.

At Gustav-Falke, Gryzke — a 30-year educator jaded by unfulfilled promises — stopped pinning her hopes on such prospects long ago.

And so even if she agrees that, in an ideal world, tracking wouldn’t exist, she has no intention of pulling the plug on the controversial program.

It’s important to recognize, she says, that the world isn’t ideal.

“You have to give parents a credible insurance that their children will have a good learning environment,” she said. “That’s how you get these people, and then if you have the freedom to develop, I believe we can really make schools better.“

This is third and final segment in our Berlin series. In the first story we explored the concept of the “social wall,” and in the second we traced the rise and fall of Mitte’s school integration attempt.

Some interviews were conducted in German. Translations and other reporting support by Nanette Kröker.

Read the full series — The Social Wall: Universal lessons in Berlin’s attempt to integrate schools

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.