He came to the U.S. legally as the son of a soldier. Now ‘one mistake’ could have him deported to Vietnam

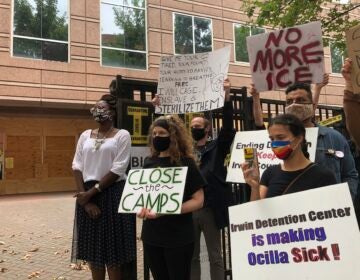

About 40 people rallied in South Philly Sunday in support of Vietnamese and Cambodian immigrants threatened with deportation, some for decades-old crimes.

-

Hung Le, of Mount Pocono, Pa., has lived in the U.S. for more than 25 years. He came legally from Vietnam as the son of a U.S. service member, but could be deported because of a crime he committed in 1992. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Spoken word poet Dianne Le performs at a protest to end deportations at a shopping center on West Oregon Avenue in Philadelphia on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2019. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Members and supporters of Philadelphia’s Southeastern Asian community carry a history dragon to protest deportations at a shopping center on West Oregon Avenue on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2019. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Members and supporters of Philadelphia’s Southeastern Asian community carry a history dragon to protest deportations at a shopping center on West Oregon Avenue on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2019. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Members and supporters of Philadelphia’s Southeastern Asian community carry a history dragon to protest deportations at a shopping center on West Oregon Avenue on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2019. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Members and supporters of Philadelphia’s Southeastern Asian community protest deportations at a shopping center on West Oregon Avenue on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2019. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Members and supporters of Philadelphia’s Southeastern Asian community protest deportations at a shopping center on West Oregon Avenue on Sunday, Jan. 27, 2019. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Nancy Nguyen is executive director of VietLead. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

In 1992, Hung Le got in trouble with the law.

The son of a U.S. service member and a Vietnamese mother, Le had recently arrived in Philadelphia, following a short stint in Virginia, thanks to the Amerasian Homecoming Act, which helped children of U.S. soldiers get immigration status in this country.

Le said his employer at the time roped him into helping commit a robbery, for which he was arrested. At the age of 22 and unfamiliar with the U.S. legal system, he pleaded guilty to charges including theft, simple assault, and conspiracy, and he served eight years probation.

Now, Le is one of an estimated 7,000 Vietnamese immigrants newly threatened with deportation due to old criminal offenses after decades in the United States.

On Sunday afternoon, more than 40 Southeast Asian community members and their supporters rallied outside a shopping center on West Oregon Avenue in South Philadelphia, part of a national campaign to draw attention to increased federal efforts to deport immigrants from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

Under U.S. immigration law, lawful immigrants, including green card holders, can be deported if they’ve been convicted of certain crimes.

“These are non-citizens who during previous administrations were arrested, convicted, and ultimately ordered removed by a federal immigration judge,” Katie Waldman, a spokesperson for the Department of Homeland Security, told Politico last month.

Le, who now owns a nail salon in Mount Pocono and has a child at Penn State, said he and other immigrants in his position deserve a “second chance” for crimes they committed as struggling newcomers to the U.S.

“If I crossed the line all the time, I’d understand. But I had one mistake,” he said.

At the rally, members of groups, such as Vietlead, the 1Love Movement, and the Cambodian Association of Greater Philadelphia, chanted and marched to Mifflin Square Park to highlight the menace of deportation in their communities.

“We’re here to keep our families together. We’re here to let our communities know about ICE and what’s happening,” said Nancy Nguyen, executive director of Vietlead, an organization in South Philadelphia that supports the local Southeast Asian community.

Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney, City Council members Mark Squilla and Helen Gym, and state Rep. Elizabeth Fiedler all came out in support of local Southeast Asian immigrants, who started settling in the city 40 years ago. Philadelphia is home to about 13,700 Vietnamese immigrants, according to U.S. Census numbers compiled by the Pew Research Center; nationally, more than 1.2 million Southeast Asian refugees have arrived in the United States since 1975.

“We have your back,” Kenney told the crowd.

Increased immigration enforcement against Southeast Asian refugees under the Trump administration mirrors similar efforts to remove other groups of longtime U.S. residents without permanent immigration status, such as those with Temporary Protected Status.

However, the particular histories of countries like Vietnam and Cambodia, shaped by U.S. military interventions, war, and genocide, add new wrinkles to immigration enforcement in Southeast Asian communities.

Following the Vietnam War, many refugees from that country fled because they faced retaliation or death for being allied with the U.S. and South Vietnam. For decades, lack of diplomatic relations between the two countries shielded refugees who could have otherwise been deported for committing crimes after arriving in the United States. In 2008, the American and Vietnamese governments signed a resettlement agreement, allowing the U.S. to deport Vietnamese immigrants who arrived after 1995.

The Trump administration has argued that the 2008 agreement does not bar the U.S. from deporting Vietnamese immigrants who arrived before 1995 if they have a criminal record. If Vietnam agrees to accept these deportees, more than 7,000 Vietnamese immigrants with orders of removal could be forced to leave. So far, 11 people have been deported.

Federal immigration authorities also recently stepped up deportations of Cambodian refugees with criminal records, many of whom arrived as children or young people in the U.S. fleeing the Khmer Rouge. In December, the U.S. sent back more than 40 Cambodian immigrants who had arrived as children or young people.

“Coming here, our young people were not being provided [with] resources and the support they needed to lead a productive lives,” said Rorng Sorn, a Cambodian refugee and former executive director of the Cambodian Association of Greater Philadelphia. As a result, she said some turned to crime as a way to survive being resettled into poverty.

Now, old convictions for time served could lead to deportation.

Against this backdrop, groups like Vietlead have been lobbying U.S. and Vietnamese officials to halt the detention and deportation of Southeast Asian refugees.

Community members like Hung Le remain caught in the middle. Le said he’s been cooperating with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement for years, but fears he could be detained and deported at any time.

“Vietnam doesn’t accept me. They kicked me out because they said I’m American… Now, my home [the United States], is kicking me out,” he said. “I can’t go back to Vietnam.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.