Frederick Douglass’ ‘The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro’ still resonates

Douglass proved he was not the typical Independence Day Antebellum orator when he spoke before an audience in Rochester, New York, on July 5, 1852.

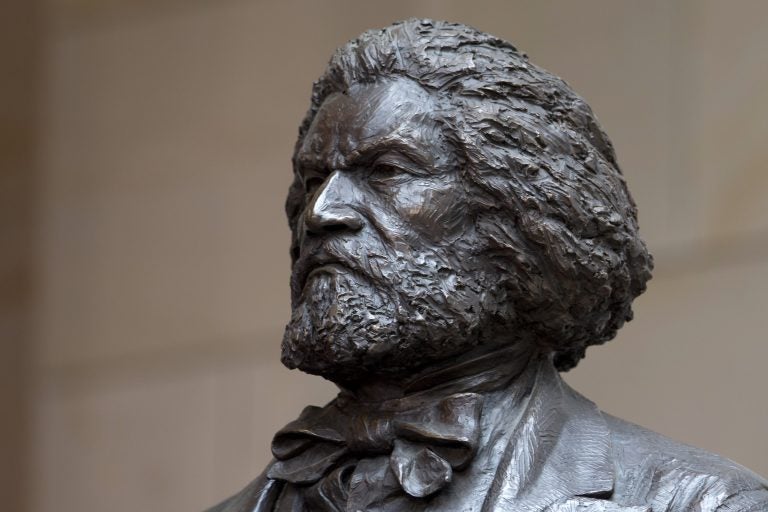

A bronze statue of 19th-century orator and writer Frederick Douglass is seen in the Emancipation Hall of the United States Visitor Center on Capitol Hill in Washington, Wednesday, June 19, 2013, where it was dedicated. The bronze statue of Douglass is by Maryland artist Steve Weitzman. (Carolyn Kaster/AP Photo)

This article originally appeared on The Philadelphia Tribune.

—

Among Frederick Douglass’ best known speeches is “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro” — with a message that still resonates 167 years later. Douglass proved he was not the typical Independence Day Antebellum orator when he spoke before an audience in Rochester, New York, on July 5, 1852. “The sunlight that brought life and healing to you, has brought stripes of death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

The fiery orator was invited to speak about what the holiday means for American Blacks to a group of approximately 500 abolitionists who each paid twelve and a half cents to hear the former slave speak. Douglass addresses his “Fellow Citizens,” all of whom where aware of his fascinating life from enslavement to equal justice and rights advocate. Soon, the keynote address becomes a condemnation of America’s support of slavery. Douglass fearless shared his opinion 11 years prior to the Emancipation Proclamation’s release of the nation’s enslaved people in 1863.

Born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey around 1818, he claimed the surname “Douglass” in 1838 after a day-long journey to freedom took him through Philadelphia to his final arrival at a New York City safe house. After marrying and settling in New England, he recast himself as an abolitionist and became an excellent orator in recounting his life story as a runaway slave.

His daring bestselling 1845 memoir — “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself” — published while slavery was still legal, was reprinted nine times in three years. One of the more memorable autobiographical stories revealed is of 15-year-old Douglass’ confrontation with Covey, a poor farmer famous for breaking a slave’s rebellious spirit. After a violent two-hour fight, the teen was never whipped again.

During the remainder of his life, the former slave would continue to garner worldwide acclaim as an in-demand lecturer. The “Narrative” was a global hit and published in Europe and translated into French and Dutch. His British supporters raised funds to purchase his freedom, and in 1847 Douglass returned to America to help abolish slavery.

Douglass’ speeches were often published in various abolitionist newspapers, including his own weekly publication, “The North Star.” A version of “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro” was also published as a booklet and is often studied in literature classes today.

In 1852, the social reformer delivered a scathing attack on the nation’s hypocrisy in celebrating democracy and freedom while nearly four million humans were being kept as slaves. “Fellow citizens, above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail of millions, whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are today rendered more intolerable by the jubilant shouts that reach them,” Douglass intoned. “To forget them, to pass lightly over their wrongs and to chime in with the popular theme would be treason most scandalous and shocking, and would make me a reproach before God and the world.”

Following the Civil War, Douglass was appointed U.S. diplomat to Haiti and became a leader in the women’s rights movements. The social crusader died after addressing the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. on Feb. 20, 1895.

Douglass, who once promised to use his “voice and pen, in season and out of season … to stand for freedom of all colors …” continues to capture the American imagination on emerging mediums in the 21st century that annually share his powerful words.

bbooker@phillytrib.com (215) 893-5749

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.