50 years ago Dr. King told these Philly kids to lay a blueprint, and they did

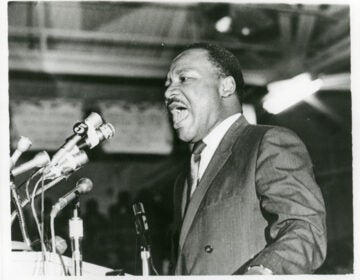

King's speech to a group of students at Barratt Junior High School in South Philadelphia urged them to make better lives. Many of them did.

Listen 5:48Dennis Kemp didn’t know who was going to climb out of the limousine.

Kemp was a ninth-grader at Barratt Junior High School in October of 1967 when his vice principal asked him and other members of the stage crew to greet a guest arriving for a special assembly.

Kemp, who played on the school’s basketball team, thought the mystery celebrity might be Philadelphia 76ers behemoth Wilt Chamberlain.

Then the car door swung open, and the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. stepped out onto South 16th Street.

“It was amazing,” Kemp said. “I’ll never forget it.”

King was in town for a star-studded rally at the Spectrum, the since-demolished sports arena King would describe that day as a “new, impressive structure.” Thanks to a connection made by legendary Philly DJ Georgie Woods (the “guy with the goods”), King stopped first at Barratt, which has since been closed.

He spoke for just 20 minutes, riveting the mostly black student body with a speech that focused on uplift, racial pride, and putting the onus on them to make better lives.

“I wanna ask you a question,” King began. “And that is: What is in your life’s blueprint?”

Fifty years later, the teenagers in that audience have answered that question and, in remarkable ways, risen to his calling. King asked them to lay a blueprint. Many did.

Jeffrey Miles hadn’t heard of King before October 26th, 1967. He was too wrapped up in street life, running with his local gang and scrapping with others.

“Every day I had to run for my life or fight for my life just to get home from school,” Miles said.

When he showed up to the surprise assembly that day, Miles was told to leave his assigned seat in the auditorium and grab one of the spare neckties piled up in one of Barratt’s rooms. They were old ties, Miles recalled, so wide and unsightly the kids called them “chest protectors.”

By the time Miles returned to the auditorium, his customary seat was no longer available, and so he grabbed another one on the aisle.

Miles was excited to see Georgie Woods, but he quickly forgot about the local music icon when King’s speech began.

“I didn’t know anything until the man opened up his mouth,” Miles recalled.

‘Learn, baby, learn’

Doors once closed to their parents were now opening for them, King said. They would have to walk through those doors despite the lingering odds against them. King acknowledged that the kind of poverty Miles and his fellow students grew up in would obstruct their path toward prosperity. But he urged them to eschew violent cynicism and instead embrace their potential.

“Our slogan must not be burn, baby, burn,” King said to raucous applause. “It must be build, baby, build, organize, baby, organize.

“Our slogan must be learn, baby, learn, so that we can earn, baby, earn.”

More than 50 years later, Miles can still recite those lines from memory. Teachers had told him before to stay in school, but this was the first time he’d internalized that message. While it would take him a couple years to completely abandon gang life, the speech galvanized him.

“That was the start,” Miles said. “That was the start for me to go on a new path to learn not to recycle poverty within myself.”

Rather than drop out as once planned, Miles went to Edward Bok Technical High School and then on to Philadelphia College of Textiles & Science (now Thomas Jefferson University). He settled into a career as an optician and went on to send three daughters to college.

He doesn’t think any of that would have happened without King’s speech, and the moment that helped seal it in his memory.

As King left the auditorium, he walked by Miles’ accidental spot on the aisle. Despite being told to remain seated, Miles felt called to jump up and ask King if he could shake his hand. King said yes.

Miles still remembers the hand, soft and a little sweaty.

“And he looked at me with those eyes,” Miles said. “And that was it. I probably just melted inside.”

A lesson in pride

Earl Wilbourn never touched King that day, but he was equally moved by the preacher’s words.

Unlike Miles, Wilbourn knew about King’s civil rights work. He’d grown up in a loving household where his mother instilled in him a sense of pride and value.

The world outside his home, however, was less kind. Society’s view of black people seemed to conflict with the messaging from his parents. King’s speech was the first time he’d heard someone outside his nuclear family tell him to take pride in his heritage.

“Don’t be ashamed of your color,” King implored. “Don’t be ashamed of your biological features.”

King focused in particular on the beauty of black hair. Wilbourn, even as a ninth-grader, understood the metaphor.

“What he was telling us was that we were just as good as anyone else,” said Wilbourn. “We could achieve just as much as anyone else. We were just as smart as anyone else.

“He made us feel like we were worth something.”

Earl Wilbourn took that feeling of self-worth and channeled it into a long teaching career in the Susquehanna Township School District just outside Harrisburg. While there, he worked to expand the district’s focus on diversity, integrating King into his regular lesson plans.

“The King visit was part of my curriculum every year,” he said. “Every year.”

Wilbourn’s classmates laid equally impressive blueprints.

Lawrence “Snuffy” Smith became captain of the Shaw University basketball team and earned induction into his conference’s Hall of Fame. Andre McCarter won a national basketball championship at UCLA under coach John Wooden and played three seasons in the NBA.

In 2015, the YMCA of the USA hired Barratt grad Kevin Washington as its first African-American President and CEO, an accomplishment the groundbreaking King would have no doubt appreciated.

The nobility of work, perseverance

Dennis Kemp, King’s formal greeter that day, played basketball with Smith, McCarter and Washington at Barratt, but his life’s path did not unfold as cleanly as theirs.

In the late 2000s, he found himself coaching basketball and working maintenance at an area private school. He loved the job, he says. He devoted himself to the Boys “B” team, working with kids other coaches had cast aside.

There’s a section in King’s “Blueprint” speech where he references the street sweeper, a metaphor he’d used before to illustrate the nobility of common work.

“If it falls your lot to be a street sweeper, sweep streets like Michelangelo painted pictures.” King said. “Sweep streets like Beethoven composed music.”

Dennis Kemp tried to become that virtuoso street sweeper, but a personal dispute with another basketball coach led to his dismissal, he said. Soon after his wife left, too, and he suffered two medical setbacks.

He wound up homeless for about fourth months.

As his life crumbled, Kemp thought back to the end of King’s speech, where he quoted a poem by Langston Hughes called “Mother to Son.” The piece begins:

“Well, son, I’ll tell you: Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.”

The words rang with Kemp. He’d grown up poor, one of nine in a family where, on some nights, his mother would gently suggest he find a friend’s family to feed him.

Life hadn’t been a crystal stair for Kemp. And now, as he hit bottom, he thought back to the final sentence of King’s talk, a message of perseverance delivered to kids who, King knew, had probably seen much in their young lives and would endure much more in the years ahead.

“If you can’t fly, run. If you can’t run, walk. If you can’t walk, crawl,” King said. “But by all means, keep moving.”

Kemp would repeat those words to himself as he grappled with the despair of homelessness.

“I would walk the streets at nights, some of the coldest nights,” he said. “One of the first things that came to my mind was Dr. King said, ‘Keep moving.’”

Kemp did. He kept moving. He says he’s living in a home in South Philadelphia these days. Every now and again, he’ll catch a rerun of King’s Barratt speech on the School District of Philadelphia’s cable access channel.

He always watches until the end.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.