For more summer, go South… or way North

ListenSummer ended at 10:29 p.m. Monday. If we were on Mars we could enjoy summer for a whole 6 months, thanks to it’s two year orbit around the sun! Cassini descends to 875 miles above Titan in its 101st close flyby of Saturn’s moon. Objective is to look at the seas and lakes of the north polar region, look at a big crater near the equator and dunes in the drier regions elsewhere on Saturn’s most likely moon to have a chemical environment similar to the early earth. Cassini arrived in 2004, completed its primary mission in 2008 and is now working on its extended mission through 2017.

September 22, 2014

-

Photo by Flickr user snbi71

[Dave Heller] Let’s savor the final moments of summer. Fall arrives in, let’s see, a little over four hours. Let’s go for the gusto with Derrick Pitts, chief astronomer at the Franklin Institute. Derrick, in astronomy-speak, what happens at exactly 10:29 tonight?

[Derrick Pitts] Well it might seem like it’s fairly momentous, that some great thing occurs at exactly that time. It is the instant that the Earth reaches a particular point in its orbit around the sun. And that particular point actually marks the time when the sun actually — as it would appear in our sky — reaches a particular point in the sky as well. So it’s these two things, really.

Particular, but a man-made arbitrary point.

Well in fact, that’s a really good way to split the two out. Because on the one hand, there’s the arbitrary man-made decision of when summer’s over. And the most colloquial definition of that is Labor Day, of course. However, summer continues to hang on as a season, astronomically speaking, until the Earth reaches this particular point in its orbit around the sun. And then we have the switch — really — from summer into fall. And even at that point, you can’t go out into space and see something in particular; but then again, it is the appearance of the sun in the sky at a particular point that helps to define that for us here on Earth.

Though if you like longer summer seasons, either head south toward the equator or way north to Mars.

[Laughs] Yeah, that’s true. You can continue your enjoyment of summer, as you mentioned, just go to the south. Because here on this planet, the seasons are actually switchable from north to south. So for those of us on the northern hemisphere, we’re switching from summer to fall while those folks on the southern end of the planet are switching from spring to summer. So you can continue this all year round if you’d like, just changing hemispheres.

But if you’d really like to have a long summer, you can go all the way out to the planet Mars. The deal is that as you move out from the center of the solar system farther away from the sun, the time it takes the planet to orbit the sun increases dramatically. So for example, here on Earth the figure we’re most familiar with is 365 and a quarter days to orbit the sun. If you go out to Mars, it takes two years for Mars to orbit the sun. And we can continue increasing all the way out to Pluto, where it takes 248 years to orbit the sun once. Now the interesting things about the two planets there — Mars and Pluto — is that because Mars has an orbit that’s two years long, summer there lasts twice as long. Each season lasts twice as long as on Earth. So instead of 3 months, you have 6 months.

-

Eight Planets and Solar System Designations. Credit: International Astronomical Union / NASA

If you go out to Pluto — oh my goodness. What a change you have there. And it doesn’t really divide out very easily because it’s such an elliptical orbit; that even causes some difficulty too, because what you might want to measure in that particular instance is at one point is Pluto at its closest point to the sun? When is perihelian for that planet, and does that actually play a role? As opposed to the seasonal aspect, which is just the planet on its rotational axis, tipping back and forth toward and away from the sun. Well, that axial tilt may not have such a big effect as the perihelian effect. And here’s where the big difference comes in: About 20 years out of the 248 year orbit of Pluto actually brings Pluto closer to the sun, to its closest point, it’s perihelian. So you could say in one way, summer on Pluto lasts about 20 years. But then you have another 228 years of winter. But since we’re thinking of it as Pluto, there really isn’t very much difference at all. So it’s absolutely frigid winter versus not quite so frigid winter. But, all of it is easily 200 degrees below zero.

Let’s stay between Mars and Pluto: What’s going on on Saturn?

We’ve had a spacecraft out at Saturn, orbiting very, very close, bringing all sorts of data and information back since 2004. That would be the Cassini spacecraft. In fact, just after it arrived it dropped off a smaller spacecraft that actually landed on one of the moons, on the moon of Titan, in January of 2005. Since that time as Cassini has been orbiting, it’s been making close passes to the largest moon, Titan, and another one of those just happened this morning. It was the 101st close fly-by of the moon Titan by the Cassini spacecraft, and that fly-by was early this morning, about 875 miles above the surface. These spacecraft have been providing us all sorts of interesting data about the planet, about its ring system and about its moon system, helping us better understand these gas giants — the magnetic fields that are there, how these rings would be formed and evolve. I think Titan is a really fine example because as the spacecraft orbits just 875 miles above, it’s going to be looking to see what kinds of lakes and other puddles, if you will, of liquid methane are found near the north polar region of the planet. On this planet’s cooler days, it actually rains methane down through the atmosphere of Titan and creates these streams, lakes and puddles of liquid methane. And that gives you a hint as to the seasonal temperature there too; again, a good 150 – 200 degrees below zero.

-

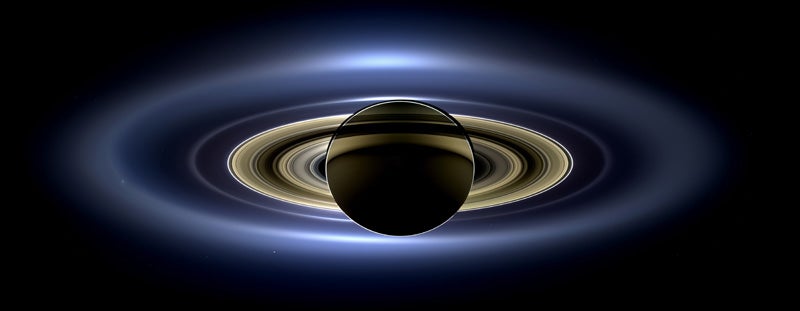

In this natural color mosaic image provided by NASA on Tuesday Nov. 12, 2013, Saturn eclipses the Sun as seen by the Cassini spacecraft on July 19, 2013. This image spans about 404,880 miles (651,591 kilometers) across. (AP Photo/NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI, File)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.