Setting right a composer’s ‘unjust malaise’

Listen

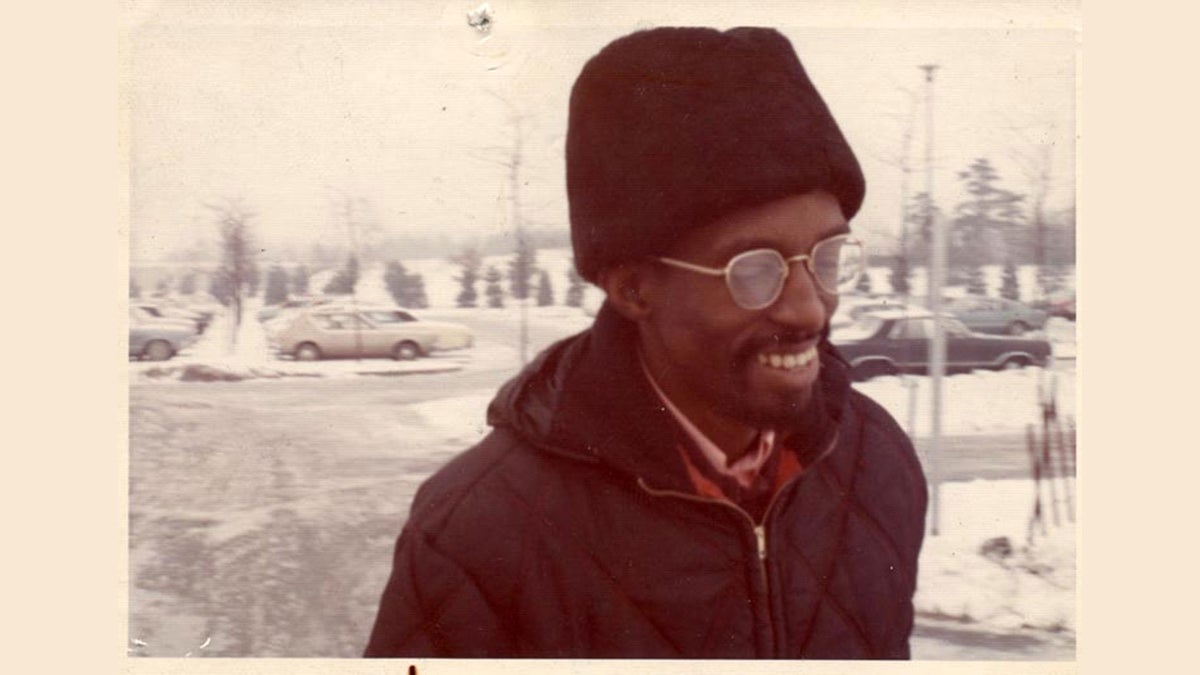

Julius Eastman in the parking lot of Baird Hall, Buffalo c. 1970. (Photographer unknown)

This month, the West Philadelphia organizations Bowerbird and the Slought Foundation are mounting “That Which is Fundamental,” a two-pronged retrospective of Julius Eastman, a twentieth century composer with a Philly connection.

At first glance, Eastman’s story is a classic tale of wasted talent, a life cut short.

But…it’s complicated.

Julius Eastman came to Philadelphia in the early 1960s to attend the Curtis Institute of Music. After growing up in a working class black neighborhood, the rarified atmosphere of Curtis was a tough fit.

It wasn’t his first encounter with feeling like an outsider. The African American community in his home town of Ithaca, New York, was not friendly to a gay man, either.

But Eastman’s talent carried him through. Despite having studied the instrument for only six years, he was admitted as a piano major, though ultimately he switched to composition. “He was a great choreographer, a fantastic pianist, a great composer, and a great singer. He could do it all,” recalls fellow composer David Borden.

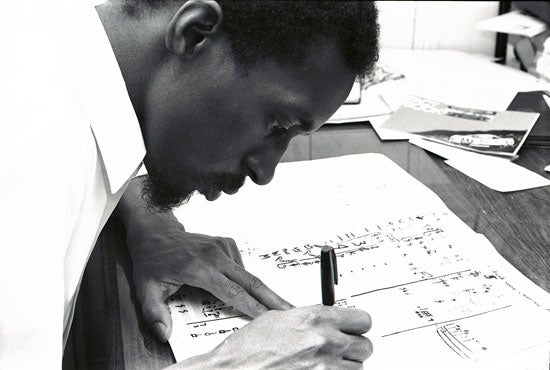

Julius Eastman composing c. 1969. Photo by Donald W. Burkhardt.

Musically, it was a revolutionary time, from free jazz, experiments in rock music, and composers breaking free from the western classical tradition. Eastman made a mark as a singer, his rich baritone voice giving the definitive performance of “Eight Songs for a Mad King,” by British composer Peter Maxwell Davies, which earned a Grammy nomination in 1973. In his own compositions, he reveled in dramatic juxtapositions, improvisation, and provocative titles and stagings.

The challenge in those freewheeling times was not the making of art, but how to make a living from it. Many composers found security in academia, but Borden says Julius Eastman wasn’t suited to that environment. “His temperament was such that he just did not feel comfortable or fulfilled in a classroom teaching situation. He could come to your class and be fantastic for an hour, but if you asked him to do that for five years of semesters, he would find that so dull.”

Eastman gravitated first to Buffalo, an epicenter of modern music at the time, then to New York City’s downtown music scene. Without a reliable source of income, he succumbed to the stresses of the city, struggling with alcohol and drugs, and becoming homeless.

Julius Eastman died in 1990, just a few months short of his 50th birthday. When he received news of Eastman’s death, David Borden commemorated his friend with an anagram of his name. “It came out ‘Unjust malaise.’ And I thought, that’s perfect. It doesn’t seem just, or he didn’t have justice during his life.”

For years, it seemed like the story would end there. But recently, there’s been a resurgence of interest in Eastman’s work, beginning with a landmark three-disc recording in 2005 (borrowing Borden’s anagram Unjust Malaise for its title). A book about his life, a video of one of his piano works, and an homage by interdisciplinary artist Jace Clayton followed. And now this month, “That Which is Fundamental.”

Co-curator Dustin Hurt says the discovery of some of Eastman’s work previously thought to be lost made this project especially appealing for him. “There was this possibility of being able to engage with something that could actually change and develop, and the new material you would find as a result of the research.”

In selecting the music program, Hurt wanted to reflect the wide range of Eastman’s musical interests. “We took the opportunity to engage with lots of different musicians,” he explains. “There are musicians involved that only do orchestra gigs, and they’re sitting right next to someone in the Sun Ra Arkestra. This is something that the openness of Julius’s music really allows.”

That openness includes leaving many decisions to the performers, even which instruments to use. “There’s three pieces that are written for multiples of any instrument,” says Hurt. “They’re most often performed on four grand pianos, because there’s a recording Julius did that way, but they’re written for any number of instruments that are the same. And so we are doing one of them. The piece is called ‘Gay Guerilla,’ as in guerilla warfare, often performed as a piece for four pianos, which I’m doing a special version of for 15 electric guitars.”

Co-curator Tiona Nekkia McClodden created the companion visual exhibits, “Predicated” and “A Recollection. “I’m looking at notions of absence, archival trace, exhaustion in terms of pushing everything to the limit,” she says. She arranged photographs, scores and other Eastman artifacts, and then explored relationships between Eastman’s practice and the work of ten contemporary artists, selecting “folks who I felt I could talk about in relation to Eastman’s biography and some of his works.”

All this activity, nearly 30 years after his death, raises the question, why now? Hurt thinks one reason is a change of views about race, brought about by recent events. “I think something really shifted in the public consciousness,” he says. “An awareness of people of color, African American artists and how they’re being perceived, both historically and now, and this fit in to a wider context of what was going on, with police shootings and the political climate. And also there’s a desire in some sense to put it right, that I think is different than at other times in history.”

As a queer African American woman, Tiona McClodden has personal reasons for her interest. “I think in hostile political times when people feel silenced, they look to people who were pushing it, of like how to bring their own personal identity within very conservative spaces. And Eastman was pushing it in terms of art.”

Among the writers and presenters now exploring the work of Julius Eastman, many want to reclaim his legacy and music from the narrative that threatened to consume it, when he died. “There’s this story of tragedy that surrounds him, but his creative life extended from about 1968 til 1983 and he actually accomplished quite a lot,” Dustin Hurt notes. “He wrote about 50 compositions. He was well regarded as a singer–Grammy nominated. He performed with the New York Philharmonic, the Israeli Philharmonic, and toured the world. And I think there’s an opportunity to introduce that into the story. That this is a person who accomplished a lot.”

“Julius Eastman: That Which is Fundamental” runs through May 28th at the Slought Foundation, with concerts on Friday nights at the Rotunda.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.