PAFA hopes to reintroduce America to surrealist painter Honoré Sharrer

Honoré Sharrer is a figure of contradictions. As a teenager she was the May Queen of her private high school in San Diego. A few years later, during World War II, she was an original Rosie The Riveter, working as a steel plate welder in a shipyard in San Francisco.

She married a staunch communist academic who was blacklisted from American universities, while at the same time painting religious imagery into her canvases.

“I don’t think Sharrer was at all religious, but she was obsessed with religious iconography. Most of it was focused on Catholicism,” said Jodi Throckmorton, curator of contemporary art at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

PAFA, working with Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio, have put together a major exhibition of this now mostly forgotten artist. Sharrer rose to fame quickly as a young woman, winning major awards and have her work acquisitioned by institution while still in her 20s.

Her popularity, however, was short-lived. While she continued to work up to her death in 2009, at age 88, she never achieved the acclaim of her early career.

“Subversion and Surrealism in the Art of Honore Sharrer,” on view until September, is an attempt to bring her back into the limelight.

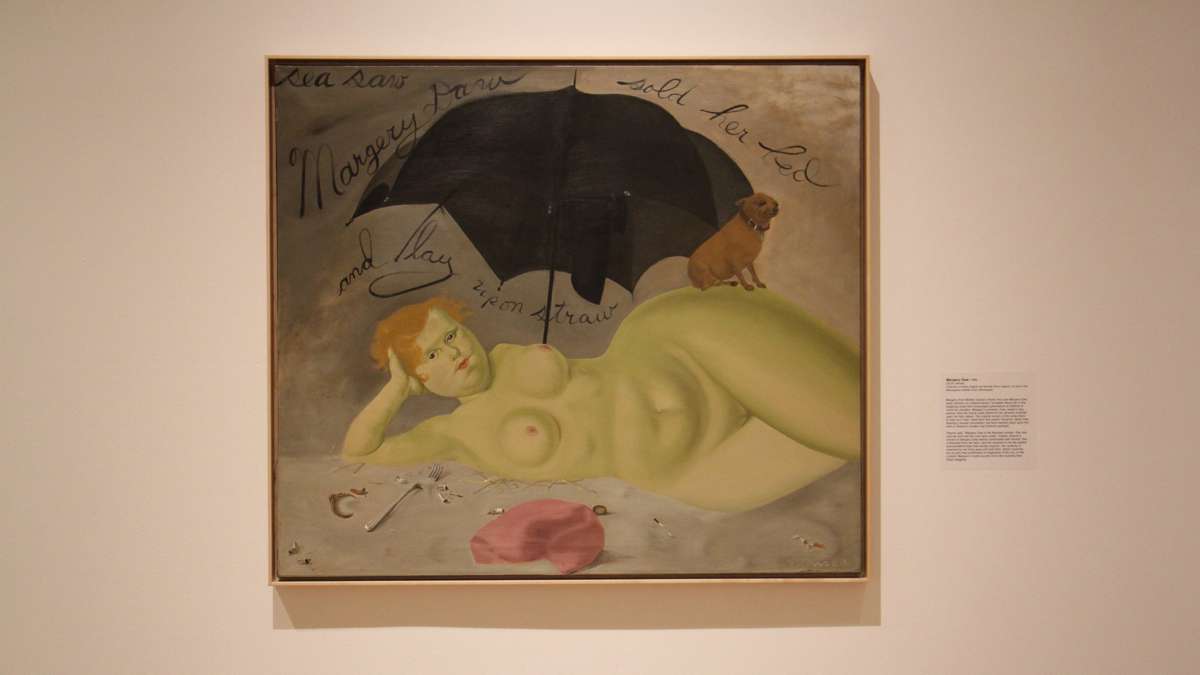

Sharrer’s paintings were realist with a surreal edge – figures were slightly out of proportion, often with sickly skin tones, surrounded by symbols that can be hard to decipher, like bent silverware, an electrical extension cord, oddly placed birds.

She also had a strong feminist and socialist political perspective. Her nudes in paintings loosely based on Greek mythology are often confidently looking at the viewer, neither demure nor seductive (irrespective of the nefarious libido of Zeus), rather affecting a certain strength.

She first came to prominence in 1943 with “Workers and Paintings,” acquired by the Museum of Modern Art, and a few years later with “Tribute to the American Working People” (1946-1951), acquired by the Smithsonian. Both are group portraits of working-class people.

“I think there was an attraction at that moment — that was the WPA moment – to this type of realist work. People were wanting a social element to the work,” said Throckmorton. “Then, with the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the post-war era and a shift in political feeling in the U.S., things got conservative. She really went out of favor.”

Sharrer continued to paint and draw until her death in 2009, often showing her work publicly but without the popularity she once enjoyed. The show, which is up until September, includes sketches the artist made at the end of her life, when she suffered from dementia.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.