Hidden in plain sight: Philadelphia as the center of the American avant-garde

A new exhibition by the University of the Arts positions Philadelphia as the heart of the mid-century American avant-garde.

Listen 1:46

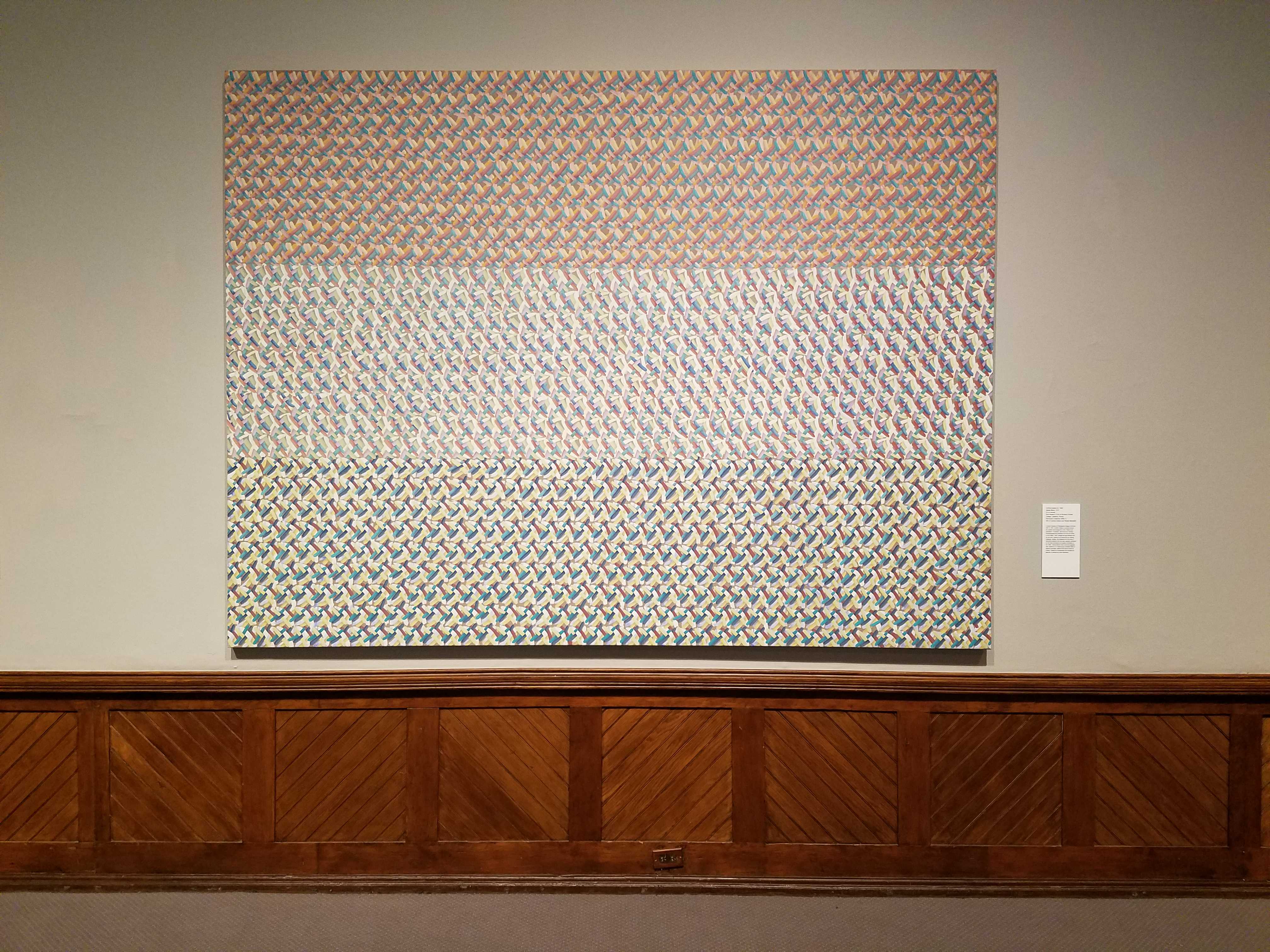

Blue Room (1970-73) by Catherine Jansen, at PAFA (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

Philadelphia was the heart of the American avant-garde in the 1960s and ’70s, according to the new art exhibition “Invisible City.”

The wide-ranging show, put together by the University of the Arts’ Sid Sachs, spreads across three campus buildings — the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, Gershman Hall, and the Philadelphia Art Alliance in Rittenhouse Square — plus a fourth location at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, or PAFA.

The exhibition brings together objects from a spectrum of disciplines — including sculpture, painting, architecture, music, performance, furniture, literature and conceptual art — to trace a network of creative thinking across many sectors of the city.

This was the era when Marcel Duchamp surprised the art world by unveiling his last major installation, “Étant donnés,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The Tyler School of Art was expanding and exploring new materials, and David Lebe was pushing the limits of photography at UArts.

The University of Pennsylvania brought groundbreaking composers George Crumb and Karl Stockhausen into its music department at the same time it was transforming its architecture school with Louis Kahn, Ian McHarg and Robert Venturi.

The Institute of Contemporary Art was created at this time at UPenn, pulling in major contemporary artists for teaching and residency positions.

“Clyfford Still taught there. David Smith taught there. Helen Frankenthaler taught there. [Robert] Motherwell taught there,” said Sachs. “It’s not in their biographies, but those people were fellows or artists in residence at Penn. Brice Marden, who is one of the most important minimalist painters, his first show was at Swarthmore College.”

The ICA gave Andy Warhol his first solo show. It also urged Agnes Martin, in 1973, to come out of her self-imposed exile in the deserts of New Mexico, where she had disappeared from the art world for several years.

The ICA exhibited several of her previously made works and invited her to deliver a lecture, “On the Perfection Underlying Life.”

Undefeated you will have nothing to say but more of the same.

Defeated you will stand at the door of your house to welcome the unknown, putting behind you all that is known.

“I heard her speak. Hearing her speak was like hearing an oracle,” said Sachs. “It had a big impact on painters. She had stopped painting for seven years. If it wasn’t for that exhibition, she might have stopped painting and there wouldn’t be anything beyond the 1960s.”

Sachs’ contention is that artists knew what was going on in Philadelphia, even if the general public did not.

“A lot of events didn’t make it into the national press, for a lot of reasons. We didn’t have a lot of galleries until the 1960s. Those galleries were kind of low budget and didn’t advertise in national magazines.”

Women were reacting to the mainstream art world in Philadelphia when they created the first major, citywide feminist art festival in 1974, “Philadelphia Focuses on Women in the Visual Arts.”

Cynthia Carlson, who taught painting at Philadelphia College of Art (now UArts), was a founder of the Pattern and Decoration movement, attempting to bring back what the men of modernism wanted to eradicate.

Carlson’s textile-inspired paintings are on view at PAFA, near a striptease video by Hannah Wilke, who disrobed for a camera looking through the partially opaque glass of Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)” at the Art Museum. Wilke, like Carlson, made strongly feminist work in reaction to the domination of male perspectives in the art world.

At the same time, across town, Venturi was likewise kicking against the stripped-down International style of architecture, creating a form of modernism that embraced decoration and even whimsy.

“I called the show ‘Invisible City’ because our city is not known as a cultural center,” Sachs said. “It should be. Philadelphia has a different take on the everyday than other cities. Everyone else is showing who did it first and when. In Philly, they wanted to know how and why. It’s a different sensibility.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.